Ecological dynamics

Loamy Floodplain ecological sites developed under Central Great Plains climatic conditions, light to severe grazing by bison and other large herbivores, sporadic natural or man caused wildfire, and other biotic and abiotic factors that typically influence soil and site development. This continues to be a disturbance driven site by herbivory, fire, and variable climate. Changes occur in the plant communities due to short term weather variations, impacts of native and/or exotic plant and animal species, and management actions. The landscape position and association with streams make this site somewhat less susceptible to fire, which allowed woody species to become more abundant than on less sheltered sites in the MLRA.

One of the primary impacts to this site introduced by European settlement of North America is season long continuous grazing by domestic livestock. This management practice causes the repeated removal of the growing point and excessive defoliation of the leaf area of individual warm-season tall grasses. The resulting reduction of the plants ability to harvest sunlight depletes the root reserves, subsequently decreasing the root mass. This negatively impacts the ability of plants to compete for life sustaining nutrients resulting in declining vigor and eventual mortality. The space created in the vegetative community is then occupied by a species that avoids the negative grazing impacts by a growing season adaptation such as a cool-season, shorter structure, or a reduced palatability mechanism.

The State and Transition Model (STM) is depicted following this section and includes a Reference State (1), a Native/Invaded Grass State (2), a Sod-busted State (3), and an Invaded Woody State (4). Each state represents the crossing of a major ecological threshold due to alteration of the functional dynamic properties of the ecosystem. The main properties observed to determine this change are the soil and vegetative communities, and the hydrological cycle.

Each state may have one or more vegetative communities that fluctuate in species composition and abundance within the normal parameters of the state. Within each state, communities may degrade or recover in response to natural and man caused disturbances such as variation in the degree and timing of herbivory, presence or absence of fire, and climatic and local fluctuations in the precipitation regime.

Interpretations are primarily based on the Reference State and have been determined by study of rangeland relic areas, areas protected from excessive disturbance, and areas under long term rotational grazing regimes. Trends in plant community dynamics have been interpreted from observation of heavily grazed to lightly grazed areas, seasonal use pastures, and historical accounts, as have plant communities, states, transitional pathways, and thresholds.

State 1

Reference State

The Reference State (1) describes the range of vegetative community phases that occur on the Loamy Floodplain ecological site where the natural processes are mostly intact. The Reference Community (1.1) is a representation of the native plant community phase that occupies a site that has been minimally altered by management. The Degraded Native Grass (1.2), the At-Risk (1.3), and the Excessive Litter (1.4) Communities are the phases that result from management decisions that are unfavorable for a healthy Reference Community (1.1). High perennial grass cover and production allows for increased soil moisture retention, vegetative production, and overall soil quality.

Dominant plant species

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), grass

-

switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), grass

-

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), grass

-

eastern gamagrass (Tripsacum dactyloides), grass

-

prairie cordgrass (Spartina pectinata), grass

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), grass

-

western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), grass

-

compassplant (Silphium laciniatum), other herbaceous

-

wholeleaf rosinweed (Silphium integrifolium), other herbaceous

-

Maximilian sunflower (Helianthus maximiliani), other herbaceous

-

goldenrod (Solidago), other herbaceous

-

white heath aster (Symphyotrichum ericoides), other herbaceous

Community 1.1

Reference Community

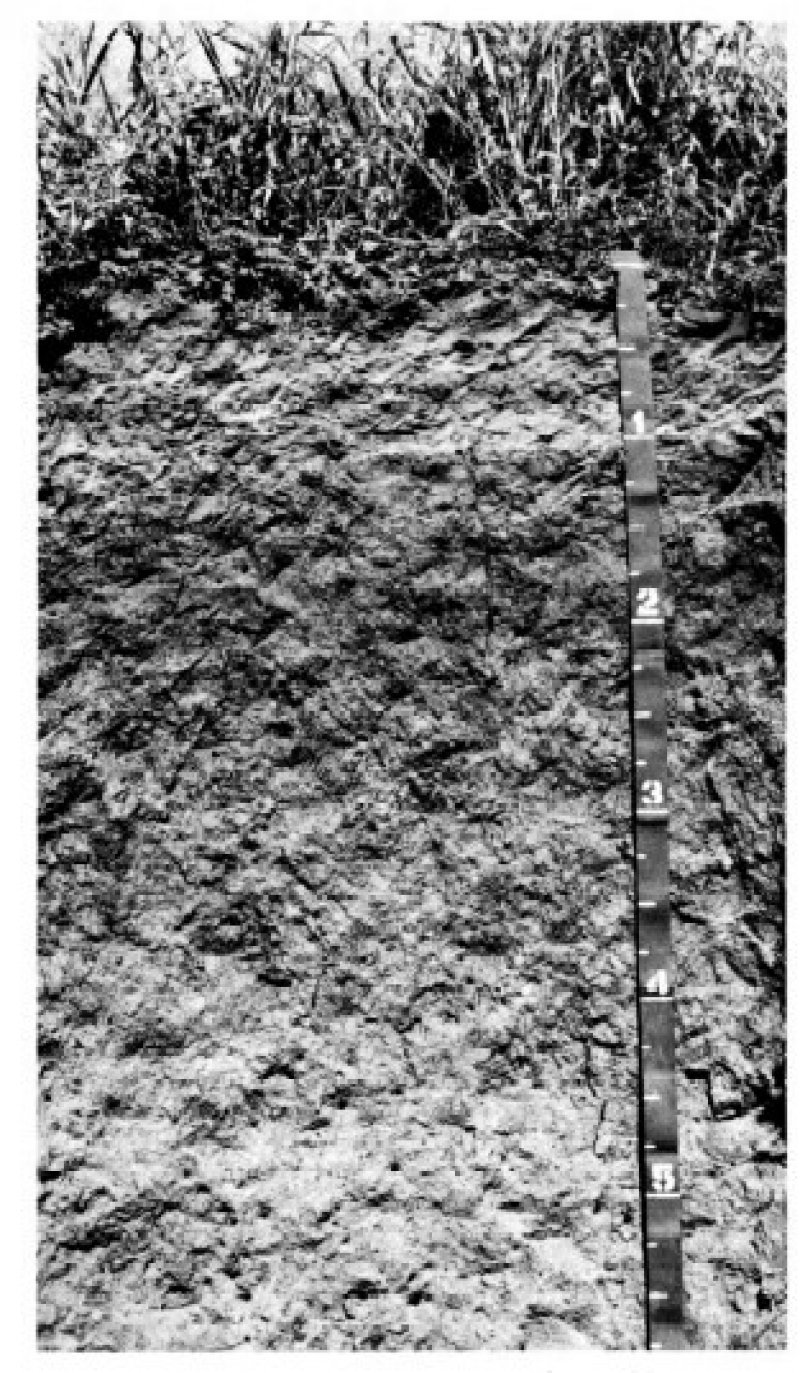

Figure 10. Loamy Floodplain ecological site, Reference Community (1.1) in Eastern Nebraska, MLRA 106.

The Reference Community or Native Tallgrass Prairie Community (1.1) serves as a description of the native plant community that naturally occurs on the site when the natural disturbance regimes are intact or are closely mimicked by management practices. This phase is dynamic, with fluid relative abundance and spatial boundaries between the dominant structural vegetative groups. These fluctuations are primarily driven by different responses of the species to changes in precipitation timing and abundance, and to fire and grazing events.

The potential vegetation consists of approximately 80 to 90 percent grasses and grass-like plants, 5 to 10 percent forbs, 0 to 5 percent shrubs, and 0 to 2 percent deciduous trees. Big bluestem, Indiangrass, eastern gamagrass, prairie cordgrass, and switchgrass are the primary species in this community. Secondary species include little bluestem, sedges, dropseed, grama grasses, and western wheatgrass. The site has a diverse forb population. A deciduous woody population also may be present.

This plant community is highly productive, diverse, and resistant to short term stresses such as drought and short periods of heavy stocking. The well-developed root systems support resiliency when allowed adequate recovery periods between grazing events.

When exposed to long term or frequent over grazing events without adequate rest, this plant community will degrade.

The average annual total vegetative production of this community ranges from a minimum of 4,000 lbs. per acre in the north, to a maximum of 9,000 lbs. per acre in the southern part of the MLRA.

The production and species data depicted in the associated species composition table are from the northern end of the MLRA and should be interpreted accordingly. Some of the species discussed in the narrative originate from sources independent of the plant table. While prairie cordgrass and eastern gamagrass are common throughout the MLRA, they were not present in the data collection projects that provided the production data for the following plant table.

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type |

Low

(lb/acre) |

Representative value

(lb/acre) |

High

(lb/acre) |

| Grass/Grasslike |

3425 |

3720 |

3820 |

| Forb |

75 |

140 |

400 |

| Shrub/Vine |

0 |

100 |

200 |

| Tree |

0 |

40 |

80 |

| Total |

3500 |

4000 |

4500 |

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Community 1.2

Degraded Native Grass Community

In the Degraded Native Grass Community (1.2), big bluestem, switchgrass, Indiangrass, eastern gamagrass, prairie cordgrass, and other desirable species lose productive capacity through loss of vigor and reproductive potential. Forb diversity is reduced. Maximillian sunflower, rosinweed, and compass plant numbers decline. Ironweed and other less palatable species increase. Warm-season mid grasses and cool-season species such as little bluestem, sideoats grama, dropseeds, western wheatgrass, and various sedges increase. Non-native, cool-season grasses may be present in trace amounts.

This community phase signals a significant loss of production. This shift in the plant community is often due to continuous, season long grazing or rotational grazing with inadequate recovery periods during the growing season. Haying with inadequate growing season recovery will also cause this change. Warm-season mid and short grasses and cool-season grasses increase. The composition of the forb component remains diverse. The potential for encroachment by invasive woody species becomes more likely due to fewer deep-rooted species and a reduced fuel load to carry fire.

While this plant community is less productive and less diverse than the Reference Community (1.1), it remains sustainable in regard to site/soil stability, hydrologic function, and biotic integrity. The average annual vegetative production in the northern portion of the MLRA is 3,200 lbs./acre.

Community 1.3

At-Risk Community

In the At-Risk Community (1.3) the more palatable warm-season tall grasses have been reduced to a minor component of the plant community with continued defoliation during their critical growth periods. Warm-season short grasses and cool-season grasses have increased significantly. Dropseeds, sideoats grama, blue grama, western wheatgrass, and sedges dominate the plant community. Non-native, cool-season grasses may be present as a minor functional/structural group and include Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome or tall fescue. Annual bromes may be present, often in abundance. Palatable forbs have been reduced, and goldenrod, ironweed, and heath aster are the dominant forbs.

Soil health is affected by reduced efficiency in the nutrient, mineral, and hydrologic cycles as a result of decreases in plant litter and rooting depths. Total annual vegetative production declines significantly. Without a management change, this community is at-risk of crossing a threshold to the Native/Invaded Grass State (2).

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Community 1.4

Excessive Litter Community

The Excessive Litter Community (1.4) develops when the natural disturbances of herbivory and fire are removed from the landscape. Litter significantly exceeds the amount expected on the site and the species present can tolerate a thatch layer. Individual plants tend to be clumped and there is an excessive amount of litter. Species that cannot tolerate an extensive litter layer have low vigor and reduced productivity.

Once the undisturbed litter layer develops to a certain level, a significant amount of precipitation is held in this layer, increasing evaporation, limiting soil available moisture, and simulating drought conditions. If herbivory or fire are not reintroduced, the plant community will experience a significant amount of death loss.

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

A shift from the Reference Community (1.1) to the Degraded Native Grass Community (1.2) occurs with continuous season long grazing or rotational grazing with inadequate growing season recovery periods (deferment). The shift can also occur when the land is hayed without adequate recovery time between cuttings.

Pathway 1.1B

Community 1.1 to 1.4

Prolonged interruption (greater than 5 years) of the natural disturbances of herbivory and fire will convert the Reference Community (1.1) to the Excessive Litter Community (1.4).

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

A shift from the Degraded Native Grass Community (1.2) toward the Reference Community (1.1) can be achieved through prescribed grazing. Applying grazing pressure during the growth period of cool-season grasses and applying deferment during the warm-season portion of the growing season favors tall grass species. This grazing strategy will enable the deeply rooted, warm-season tall grasses to recover and out compete the shallow rooted warm-season mid and short grasses and the cool-season grasses. Appropriately timed prescribed fire will accelerate this process.

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|

Pathway 1.2B

Community 1.2 to 1.3

Continuation of grazing or haying with inadequate, growing season recovery periods further degrades the Degraded Native Grass Community (1.2) to the At-Risk Community (1.3).

Pathway 1.2C

Community 1.2 to 1.4

Prolonged interruption (greater than 5 years) of the natural disturbances of herbivory and fire will convert the Degraded Native Grass Community (1.1) to the Excessive Litter Community (1.4).

Pathway 1.3A

Community 1.3 to 1.2

Reversing the downward trend which resulted in the At Risk Community (1.3) and moving toward the Degraded Native Grass Community (1.2) can be achieved with prescribed grazing early and late in the growing season to reduce the abundance of cool-season grasses. Targeting the peak growth period of cool-season grasses with high intensity grazing events followed by recovery during the warm-season portion of the growing season will allow the native, warm-season tall grasses to rejuvenate. Appropriately timed prescribed fire will accelerate this process.

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|

Pathway 1.3B

Community 1.3 to 1.4

Prolonged (greater than five years) interruption of the natural disturbances of herbivory and fire will convert the At Risk Community (1.3) to the Excessive Litter Community (1.4).

Pathway 1.4A

Community 1.4 to 1.1

Reintroduction of the natural processes of herbivory and fire will allow the vegetation of the Excessive Litter Community (1.4) to return to the Reference Community (1.1).

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|

Pathway 1.4B

Community 1.4 to 1.2

Reintroduction of the natural processes of herbivory and fire will allow the vegetation of the Excessive Litter Community (1.4) to return to the Degraded Native Grass Community (1.2).

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|

Pathway 1.4C

Community 1.4 to 1.3

Reintroduction of the natural processes of herbivory and fire will allow the vegetation of the Excessive Litter Community (1.4) to return to the At-Risk Community (1.3).

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|

State 2

Native/Invaded Grass State

The Native/Invaded Grass State (2) has transitioned from the Reference State (1) and much of the native, warm-season tall and mid grass community has been replaced by less desirable plants. The loss of warm-season tall and mid grasses has negatively impacted energy flow and nutrient cycling. Water infiltration is reduced due to the shallow root system and rapid runoff characteristics of the grazing adapted plant communities. Warm-season short grasses and cool season grasses dominant the plant communities. The Shortgrass Sod/Invaded Grass (2.1) and the Invaded Cool-Season Grass (2.2) Communities are the components of the Native/Invaded Grass State (2).

Community 2.1

Shortgrass Sod/Invaded Grass Community

The Shortgrass Sod/Invaded Grass Community (2.1) represents a shift from the Reference State (1) across a plant community threshold. With continued grazing pressure, Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome or tall fescue, blue grama and dropseeds will become the dominant plant species. Trace remnants of the more palatable warm-season tall and mid grasses may be present. Continuous and heavy grazing pressure will maintain this plant community in a sod bound condition. Forb richness and diversity has decreased, and the dominant forbs include ironweed and heath aster.

With the decline and loss of deeper penetrating root systems, a compacted layer may form in the soil profile below the shallower replacement root systems. Grazing management practices that allow for adequate periods of recovery between grazing events will favor warm-season, tall and mid grasses. Appropriately timed prescribed fire will accelerate the restoration process.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Community 2.2

Invaded Cool-Season Grass Community

The Invaded Cool-Season Grass Community (2.2) is dominated by smooth brome in the northern portion of the MLRA or tall fescue in the southern portion. Annual bromes and other annual grasses may have a significant presence. Plant diversity is very low. Some warm-season remnants may be present. Production of this plant community is highly variable, depending upon the percentages of species present, and outside inputs such as fertilizer and weed control.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

The Shortgrass Sod/Invaded Grass Community (2.1) will be converted to a smooth brome/fescue community through the following practices: Introduced grass seeding, excessive warm season grazing, inadequate warm season rest, multi season haying, and nitrogen fertilizing in the spring or fall.

State 3

Sod-busted State

The threshold to the Sod-busted State (3) is crossed as a result of mechanical disturbance to facilitate production agriculture. Extensive areas of this ecological site were plowed and converted to crop production by early European settlers and their subsequent generations. In addition to permanently altering the existing vegetative community, repeated tillage negatively impacted soil properties. Reductions in organic matter, mineral levels, soil structure, oxygen levels, and water holding capacity along with increased runoff and erosion as well as shifts in the populations of soil dwelling organisms were common on these sites. The extent of these changes depended upon the duration of cropping as well as crops grown and other management practices.

If farming operations are suspended, the site can be abandoned or seeded to permanent vegetation. Seedings are either a tame pasture forage mixture, the Seeded Pasture Community (3.2), or a mixture of native grasses and forbs, the Reseeded Native Grass Community (3.1). Abandonment results in the Natural Reclamation Community (3.3). Permanent alterations of the soil, plant community, and the hydrologic cycle make restoration to the Reference State (1) extremely difficult, if not impossible.

Community 3.1

Reseeded Native Grass Community

The Reseeded Native Grass Community (3.1) does not contain native remnants, and varies considerably depending upon the seed mixture, the degree of soil erosion, the age of the stand, fertility management, and past grazing management. Prescribed grazing with adequate recovery periods will be required to maintain productivity and desirable species.

Native range and grasslands seeded to native species are ecologically different and should be managed separately. Factors such as functional group, species, stand density, and improved varieties all impact the production level and palatability of the seedings. Species diversity is often limited, and when grazed in conjunction with native rangelands, uneven forage utilization may occur.

Total annual production during an average year varies significantly depending upon precipitation, management, and grass species seeded.

Community 3.2

Seeded Pasture Community

The Seeded Pasture Community (3.2) does not contain native remnants and varies considerably depending upon the extent of soil erosion, the species seeded, the quality of the stand that was established, the age of the stand, and management of the stand since establishment.

There are several factors that make seeded tame pasture a different grazing resource than native rangeland and land seeded to a native grass mixture. Factors such as species selected, stand density, improved varieties, and harvest efficiency all impact production levels and palatability. Species diversity on seeded tame pasture is often limited to a few species. When seeded pasture and native rangelands or seeded pasture and seeded rangeland are in the same grazing unit, uneven forage utilization will occur. Improve forage utilization and stand longevity by managing this community separately from native rangelands or land seeded to native grass species.

Total annual production during an average year varies significantly depending on the level of management and species seeded. Improved varieties of warm-season or cool-season grasses are recommended for optimum forage production.

Community 3.3

Natural Reclamation Community

The Natural Reclamation Community (3.3) consists of annual and perennial weeds and less desirable grasses. These sites have been farmed and abandoned without being reseeded. Soil organic matter and carbon reserves are reduced, soil structure is changed, and a plowpan or compacted layer can form, which decreases water infiltration. Residual synthetic chemicals may remain from farming operations. In early successional stages, this community is not stable. The hazard of erosion is a concern.

Total annual production during an average year varies significantly depending on the succession stage of the plant community and any management applied to the system.

State 4

Invaded Woody State

The Invaded Woody State (4) is the result of woody encroachment. Once the tree canopy cover reaches 15 percent with an average tree height exceeding five feet, the threshold is crossed. Woody species are encroaching due to lack of prescribed fire and other brush management practices. Typical ecological impacts are a loss of native grasses, degraded forage productivity, and reduced soil quality. This state consists of the Invaded Woody Community (4.1)

Prescribed burning, wildfire, timber harvest and brush management will move the Invaded Woody State (4) toward a grass dominated state. If the Invaded Woody State (4) transitioned from the Native/Invaded Grass State (2) or the Sod-busted State (3), the land cannot be restored to the Reference State (1) as the native plant community, soils, and hydrologic function has been too severely impacted prior to the woody encroachment to allow restoration to the Reference State.

This state consists of the Invaded Woody Community.

Dominant plant species

-

honeylocust (Gleditsia triacanthos), tree

-

elm (Ulmus), tree

-

green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), tree

-

oak (Quercus), tree

-

eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides), tree

-

eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana), tree

-

composite dropseed (Sporobolus compositus), grass

-

prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis), grass

-

western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), grass

-

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), grass

Community 4.1

Invaded Woody Community

Figure 16. Loamy Floodplain ecological site, Invaded Woody Community (4.1) in Doniphan County Kansas, MLRA 106.

The Invaded Woody Community (4.1) has at least 15 percent canopy cover consisting of trees generally 5 feet or taller. Honey locust, elm, ash, oak, and cottonwood are some of the deciduous invaders while eastern red cedar is the primary evergreen encroacher. In the absence of fire and brush management, this ecological site is very susceptible to eastern red cedar seedling invasion, especially when adjacent to a seed source. Eastern red cedar can eventually dominate the site resulting in a closed canopy monoculture which drastically reduces forage production, and which has limited value for either livestock grazing or wildlife habitat. Due to fire suppression over many years, this plant community will develop extensive ladder fuels which can lead to a removal of most tree species with a wildfire. With properly managed intensive grazing, encroachment of deciduous trees will be minimal; however, this will not impact encroachment of conifer species. The herbaceous component decreases proportionately in relation to the percent canopy cover, with the reduction being greater under a conifer overstory. Eastern red cedar control can usually be accomplished with prescribed burning while the trees are six feet tall or less and fine fuel production is greater than 1,500 pounds per acres. Larger red cedars can also be controlled with prescribed burning, but successful application requires the use of specifically designed ignition and holding techniques (https://www.loesscanyonsburngroup.com).

Re-sprouting brush and trees must be chemically treated immediately after mechanical removal to achieve effective treatment. The forb component will initially increase following tree removal. To prevent return to a woody dominated community, ongoing brush management such as hand cutting, chemical spot treatments, or periodic prescribed burning is required .This plant community is resistant to change and resilient given normal disturbances. In higher canopy cover situations, the soil erosion will increase in relation to most of the plant communities from which this plant community originated. The water cycle is also significantly altered under higher canopy cover. Infiltration is reduced and runoff is typically increased because of a lack of herbaceous cover and the rooting structure provided by the herbaceous species. Total annual production during an average year varies significantly, depending on the production level prior to encroachment and the percentage of canopy cover.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Heavy grazing or haying with inadequate recovery periods (deferment) will cause the Reference State (1) to lose a significant proportion of warm-season, tall and mid grass species and cross a threshold to the Native/Invaded Grass State (2). Water infiltration and other hydrologic functions will be reduced due to the root matting presence of sod forming grasses. With the decline and loss of deeper penetrating root systems, soil structure and biological integrity are degraded to the point that recovery is unlikely. Once this occurs, it is highly unlikely that grazing management alone will return the community to the Reference State (1).

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

The Reference State (1) is significantly altered by mechanical tillage converting site to the Sod-busted State (3) to facilitate production agriculture. The disruption to the plant community, the soil, and the hydrology of the system make restoration to a true reference state unlikely.

Transition T1C

State 1 to 4

Disruption of the natural fire regime and the encroachment of invasive exotic and native woody species can cause the Reference State (1) to shift to the Invaded Woody State (4).

Transition T 2A

State 2 to 3

The Native/Invaded Grass State (2) is significantly altered by mechanical tillage converting site to the Sod-busted State (3) to facilitate production agriculture. The disruption to the plant community, the soil, and the hydrology of the system make restoration to a true reference state unlikely.

Transition T 2B

State 2 to 4

Disruption of the natural fire regime and the encroachment of invasive exotic and native woody species can cause Native/Invaded Grass State (2) to shift to the Invaded Woody State (4).

Transition T 3A

State 3 to 4

Disruption of the natural fire regime and the encroachment of invasive exotic and native woody species can cause the Sod-busted State (3) to shift to the Invaded Woody State (4).

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 1

Prescribed burning, wildfire, harvest, and brush management will move the Invaded Woody State (4) toward the Reference State (1). The forb component of a site with heavy tree density or canopy cover may initially increase following tree removal through mechanical brush management treatments and prescribed fire. If re-sprouting brush is present, stumps must be chemically treated immediately after mechanical removal. Ongoing brush management such as hand cutting, chemical spot treatments, or periodic prescribed burning is required to prevent a return to the Invaded Woody State (4).

Land that transitioned to the Invaded Woody State (4) from the Native/Invaded Grass State (2) or the Sod-busted State (3) cannot be restored to the Reference State (1) through removal of woody species.

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|

Restoration pathway R4B

State 4 to 2

Prescribed burning, wildfire, harvest, and brush management will move the Invaded Woody State (4) toward the Native/Invaded Grass State (2). The forb component of a site with heavy tree density or canopy cover may initially increase following tree removal through mechanical brush management treatments and prescribed fire. If re-sprouting brush is present, stumps must be chemically treated immediately after mechanical removal. Ongoing brush management such as hand cutting, chemical spot treatments, or periodic prescribed burning is required to prevent a return to the Invaded Woody State (4).

Land that transitioned to the Invaded Woody State (4) from the Native/Invaded Grass State (2) or the Sod-busted State (3) cannot be restored to the Reference State (1) through removal of woody species.

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|

Restoration pathway R4C

State 4 to 3

Prescribed burning, wildfire, harvest, and brush management will move the Invaded Woody State (4) toward the Sod-busted State (3). The forb component of a site with heavy tree density or canopy cover may initially increase following tree removal through mechanical brush management treatments and prescribed fire. If re-sprouting brush is present, stumps must be chemically treated immediately after mechanical removal. Ongoing brush management such as hand cutting, chemical spot treatments, or periodic prescribed burning is required to prevent a return to the Invaded Woody State (4).

Land that transitioned to the Invaded Woody State (4) from the Native/Invaded Grass State (2) or the Sod-busted State (3) cannot be restored to the Reference State (1) through removal of woody species.

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|