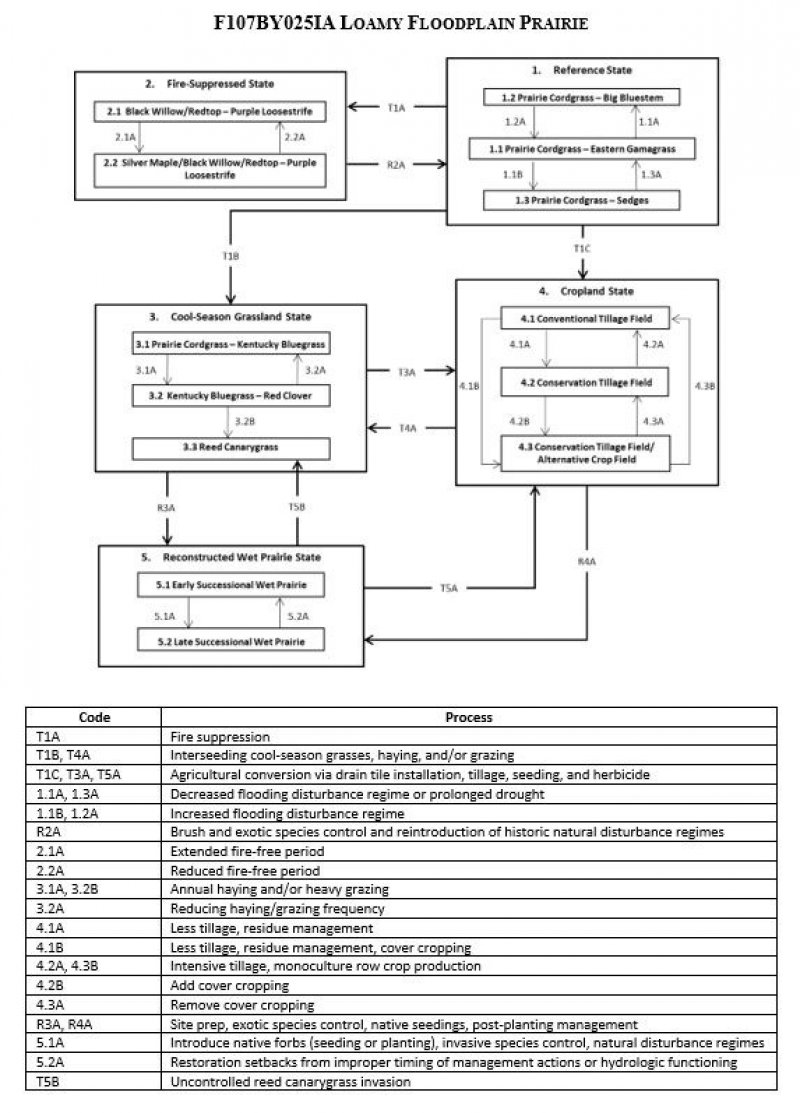

Ecological dynamics

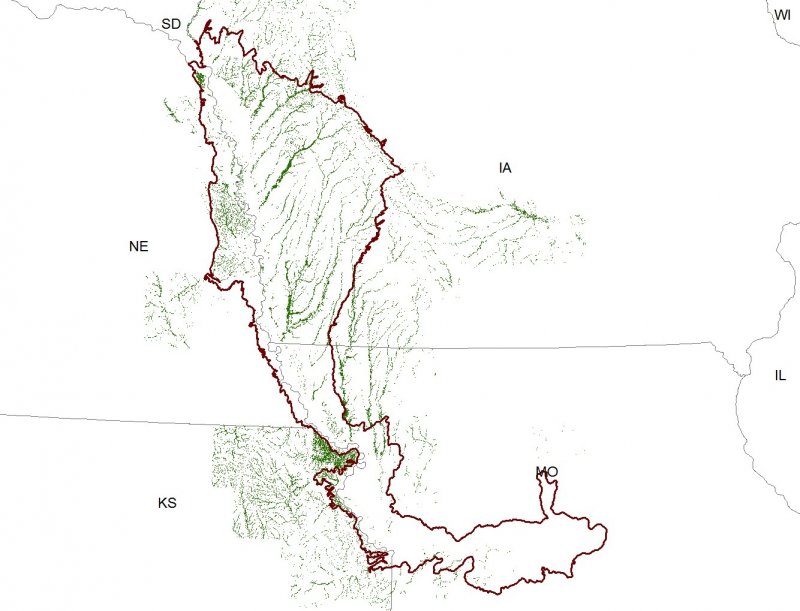

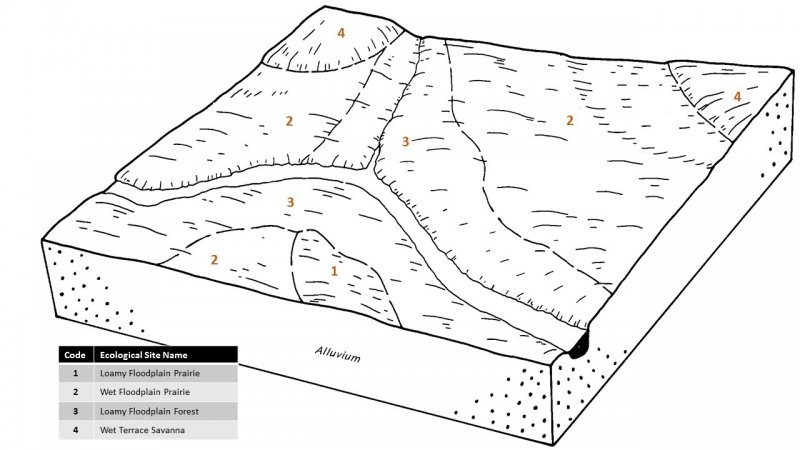

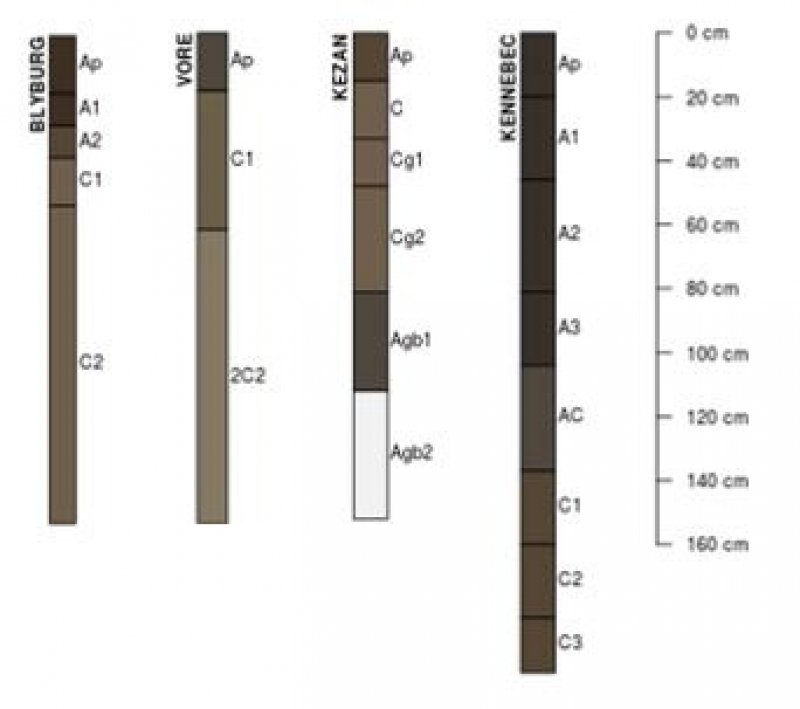

The Loess Hills region lies within the transition zone between the eastern deciduous forests and the Great Plains, with the Missouri River flowing through the middle. The heterogeneous topography of the area results in variable microclimates and fuel matrices that in turn are able to support prairies and savannas or woodlands and forests (Nelson 2010). Loamy Floodplain Prairies form an aspect of this vegetative continuum. This ecological site occurs on floodplains on moderately well-drained soils. Species characteristic of this ecological site consist of hydrophytic and mesophytic herbaceous vegetation.

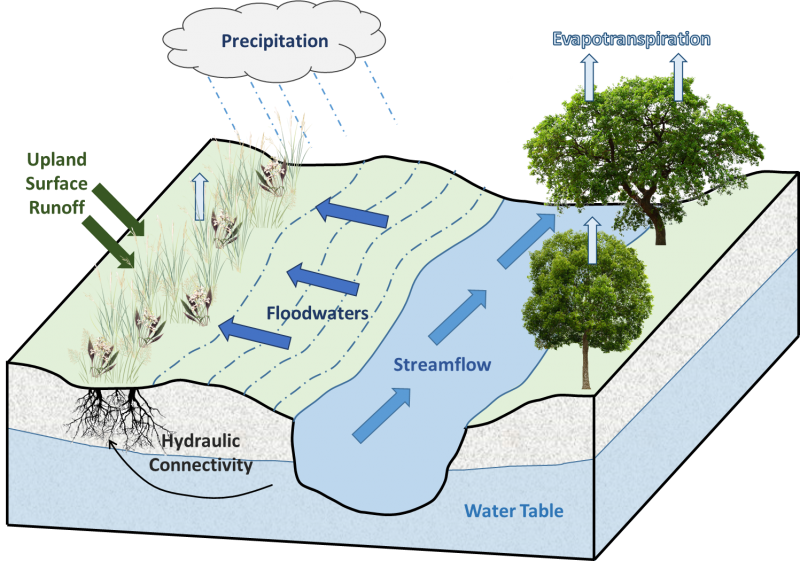

Flooding is the dominant disturbance factor in Loamy Floodplain Prairies. Seasonal flooding occurs in winter and spring, but can also follow heavy rains (Nelson 2010). Periodic, hot replacement fires every two to five years helped to reduce the build-up of heavy thatch as well as keep the site free of encroaching woody vegetation (LANDFIRE 2009). Animal herbivory is a secondary disturbance factor that can impact plant composition, diversity, and cover. Historically, occasional browsing by large ungulates, such as bison, prairie elk, and white-tailed deer, might have prevented the invasion of woody species into this bottomland prairie (Nelson 2010).

Today, many original Loamy Floodplain Prairies have been reduced as a result of drainage and clearing for agriculture. Sites have also been degraded by stream channelization, wetland drainage, and excessive siltation, which have altered hydrologic flood cycles. Fire suppression has allowed woody vegetation to invade and overtake the native prairie. Invasive species, such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria L.), reed canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea L.), redtop (Agrostis gigantea Roth), and Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.) have also been invading this site and reducing native species diversity (Nelson 2010; Steinauer and Rolfsmeier 2010).

State 1

Reference State

The reference plant community is categorized as a wet meadow community, dominated by hydrophytic and mesophytic vegetation. The three community phases within the reference state are dependent on seasonal flooding and precipitation as well as an average fire return interval of three years (LANDFIRE 2009; Nelson 2010). The amount and duration of floodwater alters species composition, cover, and extent, while regular fire intervals keep woody species from encroaching. Animal herbivory from large ungulates have more localized impacts in the reference phases, but do contribute to overall species composition, diversity, cover, and productivity (Nelson 2010).

Community 1.1

Prairie Cordgrass – Eastern Gamagrass

Sites in this reference community phase are generally diverse and consist of a wide array of grasses and forbs. The dominant species for this reference community phase are prairie cordgrass and eastern gamagrass. Other species characteristic of this phase include switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.), Michigan lily (Lilium michiganense Farw.), common boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum L.), and groundnut (Apios americana Medik.) (Nelson 2010; Steinauer and Rolfsmeier 2010).

Community 1.2

Prairie Cordgrass – Big Bluestem

This reference community phase occurs along the drier edges of Loamy Floodplain Prairies that grade into drier upland prairies. It can also occur as a result of prolonged drought. Prairie cordgrass and big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii Vitman) are the dominant and diagnostic species for this phase. Other species that can occur in this phase include prairie milkweed (Asclepias sullivantii Engelm. ex A. Gray), bluejacket (Tradescantia ohiensis Raf.), and lanceleaf loosestrife (Lysimachia lanceolata Walter) (Nelson 2010).

Community 1.3

Prairie Cordgrass – Sedges

This reference community phase occurs along the moister edges of Loamy Floodplain Prairies that grade into other wet floodplain prairies. It can also occur from increased flooding. Prairie cordgrass and various sedges (Carex laeviconica Dewey, Carex annectens (E.P. Bicknell) E.P. Bicknell, Carex pellita Muhl. ex Willd.)) are the dominant and diagnostic species of the site. Other species characteristic of this phase include bluejoint, green bulrush (Scirpus atrovirens Willd.), prairie ironweed (Vernonia fasciculata Michx.), and northern bog violet (Viola nephrophylla Greene) (Nelson 2010; Steinauer and Rolfsmeier 2010).

Pathway P1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Natural succession as a result of decreased flooding or prolonged drought.

Pathway P1.1B

Community 1.1 to 1.3

Natural succession as a result of increased flooding.

Pathway P1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Natural succession as a result of increased flooding.

Pathway P1.3A

Community 1.3 to 1.1

Natural succession as a result of decreased flooding or prolonged drought.

State 2

Fire Suppressed State

Fire suppression can transition the reference herbaceous wet meadow community into a shrub-dominated community. Historically, hot replacement fires occurred on a two to five year cycle and helped to reduce woody encroachment and thatch build-up (LANDFIRE 2009). Over the past 150 years, however, fire suppression policies have allowed shrubs and trees to succeed into areas they did not historically occur.

Community 2.1

Black Willow/Redtop – Purple Loosestrife

In this community phase, fire has been eliminated from the landscape in excess of five years. Woody species have begun to encroach on the herbaceous marsh. The dominant shrub overtaking the reference community is black willow (Salix nigra Marshall). While native species can persist, continued fire suppression can also lead to invasion of exotic species such as redtop and purple loosestrife (Nelson 2010).

Community 2.2

Silver Maple/Black Willow/Redtop – Purple Loosestrife

Sites in this community phase have continued to have fire suppressed from the landscape, allowing the woody canopies to mature. Silver maple (Acer saccharinum L.) becomes a dominant tree, and black willow continues to maintain the shrub canopy.

Pathway P2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Continued fire suppression

Pathway P2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Single fire event within 20 years.

State 3

Cool Season Pasture State

The cool-season grassland state occurs when the reference state has been anthropogenically-altered for livestock and/or hay production. Interseeding of non-native cool-season grasses, annual mowing, and grazing by domesticated livestock transition and maintain this simplified grassland state. Over time, as lands were continually grazed by large herds of cattle, native plant species diversity decreases and the non-native species were able to spread and expand across the prairie habitat (Nelson 2010; Steinauer and Rolfsmeier 2010).

Community 3.1

Prairie Cordgrass – Kentucky Bluegrass

Sites in this community phase arise from interseeding non-native forage species followed by grazing and/or haying. Prairie cordgrass can persist in the early phases due to its high grazing resistance and haying tolerance, but will decrease under intensive pressure (Walkup 1991). Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.) is a commonly planted forage species and is well-adapted to moist conditions (Uchytil 1993).

Community 3.2

Kentucky Bluegrass- Red Clover

This community phase represents increasing grazing and continuous haying. Kentucky bluegrass and red clover (Trifolium pratense L.) are characteristic species of frequently mowed sites. Other non-native species that can increase under these anthropogenically-induced conditions include alsike clover (Trifolium hybridum L.), timothy (Phleum pratense L.), and reed canarygrass (Steinauer and Rolfsmeier 2010).

Community 3.3

Reed Canarygrass

This community phase represents a near-to-complete exclusion of the native wet prairie species by reed canarygrass. This species regenerates aggressively by seed, seed banking, and vegetative regeneration. Disturbance may aid establishment, but it is not a requirement for colony spread. Monotypic stands are believed to influence and complicate successional pathways, especially in sites affected by nutrient enrichment from agricultural runoff (Green and Galatowitsch 2002; Kercher et al. 2007; Waggy 2010).

Pathway P3.1A

Community 3.1 to 3.2

Annual haying and/or continuous grazing frequency increased.

Pathway P3.2A

Community 3.2 to 3.1

Haying and grazing frequency reduced.

Pathway P3.2B

Community 3.2 to 3.3

Annual haying and/or grazing frequency increased.

State 4

Cropland State

The Midwest is well-known for its highly-productive agricultural soils, and as a result, much of the MLRA has been converted to cropland, including portions of this ecological site (USGS 1999). Agricultural tile drains used to lower the water table and continuous use of tillage, row-crop planting, and chemicals (i.e., herbicides, fertilizers, etc.) have effectively eliminated the reference community and many of its natural ecological functions in favor of crop production. Corn (Zea mays L.) and soybeans (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) are the dominant crops for the site. These areas are likely to remain in crop production for the foreseeable future.

Community 4.1

Conventional Tillage Field

Sites in this community phase typically consist of monoculture row-cropping maintained by conventional tillage practices. They are cropped in either continuous corn or corn-soybean rotations. The frequent use of deep tillage, low crop diversity, and bare soil conditions during the non-growing season negatively impact soil health. Under these practices, soil aggregation is reduced or destroyed, soil organic matter is reduced, erosion and runoff are increased, and infiltration is decreased, which can ultimately lead to undesirable changes in the hydrology of the watershed (Tomer et al. 2005).

Community 4.2

Conservation Tillage Field

This community phase is characterized by rotational crop production that utilizes various conservation tillage methods to promote soil health and reduce erosion. Conservation tillage methods include strip-till, ridge-till, vertical-till, or no-till planting systems. Strip-till keeps seedbed preparation to narrow bands less than one-third the width of the row where crop residue and soil consolidation are left undisturbed in-between seedbed areas. Strip-till planting may be completed in the fall and nutrient application either occurs simultaneously or at the time of planting. Ridge-till uses specialized equipment to create ridges in the seedbed and vegetative residue is left on the surface in between the ridges. Weeds are controlled with herbicides and/or cultivation, seedbed ridges are rebuilt during cultivation, and soils are left undisturbed from harvest to planting. Vertical-till systems employ machinery that lightly tills the soil and cuts up crop residue, mixing some of the residue into the top few inches of the soil while leaving a large portion on the surface. No-till management is the most conservative, disturbing soils only at the time of planting and fertilizer application. Compared to conventional tillage system, conservation tillage methods can reduce soil erosion, increase organic matter and water availability, improve water quality, and reduce soil compaction.

Community 4.3

Conservation Tillage Field/Alternative Crop Field

This condition applies conservation tillage methods as described above as well as adds cover crop practices. Cover crops typically include nitrogen-fixing species (e.g., legumes), small grains (e.g., rye, wheat, oats), or forage covers (e.g., turnips, radishes, rapeseed). The addition of cover crops not only adds plant diversity but also promotes soil health by reducing soil erosion, limiting nitrogen leaching, suppressing weeds, increasing soil organic matter, and improving the overall soil. In the case of small grain cover crops, surface cover and water infiltration are increased, while forage covers can be used to graze livestock or support local wildlife. Of the three community phases for this state, this phase promotes the greatest soil sustainability and improves ecological functioning within a cropland system.

Pathway P4.1A

Community 4.1 to 4.2

Tillage operations are greatly reduced, crop rotation occurs on a regular schedule, and crop residue is allowed to remain on the soil surface.

Pathway P4.1B

Community 4.1 to 4.3

Tillage operations are greatly reduced or eliminated, crop rotation is either reduced or eliminated, and crop residue is allowed to remain on the soil surface, and cover crops are implemented to prevent soil erosion.

Pathway P4.2A

Community 4.2 to 4.1

– Intensive tillage is utilized and monoculture row-cropping is established.

Pathway P4.2B

Community 4.2 to 4.3

Cover crops are implemented to prevent soil erosion.

Pathway P4.3B

Community 4.3 to 4.1

Intensive tillage is utilized, cover crops practices are abandoned, monoculture row-cropping is established, and crop rotation is reduced or eliminated.

Pathway P4.3A

Community 4.3 to 4.2

Cover crop practices are abandoned.

State 5

Reconstructed Wet Prairie State

Prairie reconstructions have become an important tool for repairing natural ecological functioning and providing habitat protection for numerous grassland-dependent species. The historic plant community of wet prairie was extremely diverse and complex, and prairie replication is not considered to be possible once the native vegetation has been altered by post-European settlement land uses. Therefore ecological restoration should aim to aid the recovery of degraded, damaged, or destroyed ecosystems. A successful restoration will have the ability to structurally and functionally sustain itself, demonstrate resilience to the natural ranges of stress and disturbance, and create and maintain positive biotic and abiotic interactions (SER 2002). The reconstructed wet prairie state is the result of a long-term commitment involving a multi-step, adaptive management process. Diverse, species-rich seed mixes are important to utilize as they allow the site to undergo successional stages that exhibit changing composition and dominance over time (Smith et al. 2010). On-going post-planting management will help the site progress from an early successional community dominated by annuals and some weeds to a later seral stage composed of native perennial grasses, sedges, and forbs.

Community 5.1

Early Successional Reconstructed Wet Prairie

This community phase represents the early community assembly from prairie reconstruction and is highly dependent on the seed mix utilized and the timing and priority of planting operations. The seed mix should look to include a diverse mix of native cool-season and warm-season annual and perennial grasses and forbs typical of the reference state. Cool-season annuals can help to provide litter that promotes cool, moist soil conditions to the benefit of the other species in the seed mix. The first season following site preparation and seeding will typically result in annuals and other volunteer species forming the vegetative cover (Steinauer et al. 2003). Control of non-native species, particularly perennial species, is crucial at this point in order to ensure they do not establish before the native vegetation (Martin and Wilsey 2012). After the first season, native warm-season grasses should begin to become more prominent on the landscape and, over time, close the canopy.

Community 5.2

Late Successional Reconstructed Wet Prairie

Appropriately timed disturbance regimes (e.g., seasonal flooding, prescribed fire) applied to the early successional community phase can help increase the beta diversity, pushing the site into a late successional community phase over time. While prairie communities are dominated by grasses, these species can suppress forb establishment and reduce overall diversity and ecological functioning (Martin and Wilsey 2006; Williams et al. 2007). Reducing accumulated plant litter from such tallgrasses as prairie cordgrass and bluejoint allows more light and nutrients to become available for forb recruitment, allowing for greater ecosystem complexity (Wilsey 2008).

Pathway P5.1A

Community 5.1 to 5.2

Selective herbicides are used to control non-native species, and prescribed fire and/or light grazing help to increase the native species diversity and control woody vegetation.

Pathway P5.2A

Community 5.2 to 5.1

Reconstruction experiences a decrease in native species diversity from drought or improper timing of management actions (e.g., lack of flooding, reduced fire frequency, use of non-selective herbicides).

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Transition 1A – Long-term fire suppression transitions this site to the fire-suppressed state (2).

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Transition 1B – Interseeding of cool-season grasses and annual mowing and/or grazing transition this site to the cool-season grassland state (3).

Transition T1C

State 1 to 4

Transition 1C – Installation of drain tiles, tillage, seeding of agricultural crops, and non-selective herbicide transition this site to the cropland state (4).

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Restoration 2A – Re-establishment of a historic fire regime and non-native species control transitions this site to the reference state (1).

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

Transition 3A – Installation of drain tiles, tillage, seeding of agricultural crops, and non-selective herbicide transition this site to the cropland state (4).

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 5

Restoration 3A – Site preparation, exotic species control, native species seeding, and post-planting management transition this site to the reconstructed wet prairie state (5).

Restoration pathway T4A

State 4 to 3

Transition 4A – Interseeding of cool-season grasses and annual mowing and/or grazing transition this site to the cool-season grassland state (3).

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 5

Restoration 4A – Removal of drain tiles, site preparation, native seeding, and invasive species control transition this site to the reconstructed wet prairie state (5).

Restoration pathway T5B

State 5 to 3

Transition 5B – Uncontrolled reed canarygrass invasions transition this site to the cool-season grassland state (3).

Transition T5A

State 5 to 4

Transition 5A – Tillage, seeding of agricultural crops, and non-selective herbicide transition this site to the cropland state (4).