Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site F116BY001MO

Fragipan Upland Woodland

Last updated: 10/06/2020

Accessed: 02/27/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

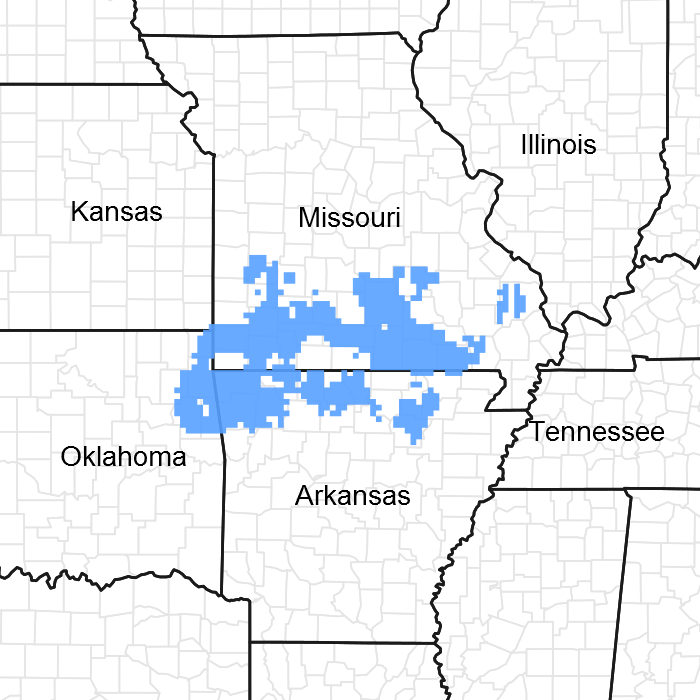

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 116B–Springfield Plain

The Springfield Plain is in the western part of the Ozark Uplift. It is primarily a smooth plateau with some dissection along streams. Elevation is about 1,000 feet in the north to over 1,700 feet in the east along the Burlington Escarpment adjacent to the Ozark Highlands. The underlying bedrock is mainly Mississippian-aged limestone, with areas of shale on lower slopes and structural benches, and intermittent Pennsylvanian-aged sandstone deposits on the plateau surface.

Classification relationships

Terrestrial Natural Community Type in Missouri (Nelson, 2010):

The reference state for this ecological site is most similar to an Upland Flatwoods.

Missouri Department of Conservation Forest and Woodland Communities (Missouri Department of Conservation, 2006):

The reference state for this ecological site is most similar to a Post Oak Woodland.

National Vegetation Classification System Vegetation Association (NatureServe, 2010):

The reference state for this ecological site is most similar to Quercus stellata - Quercus marilandica / Schizachyrium scoparium Wooded Herbaceous Vegetation (CEGL002391).

Geographic relationship to the Missouri Ecological Classification System (Nigh & Schroeder, 2002):

This ecological site occurs primarily within the following Land Type Associations:

Spring River Prairie/Savanna Dissected Plain

Springfield Karst Prairie Plain

Seymour Highland Oak Savanna/Woodland Dissected Karst Plain

Sparta Oak Savannah Plain

Ecological site concept

NOTE: This is a “provisional” Ecological Site Description (ESD) that is under development. It contains basic ecological information that can be used for conservation planning, application and land management. As additional information is collected, analyzed and reviewed, this ESD will be refined and published as “Approved”.

Fragipan Upland Woodlands occur throughout the Ozark Highlands. Within the Springfield Plain they are confined mainly to the flat to gently rolling, loess covered dissected plains in the southern half of the region, particularly around the James River, and Finley and Shoal Creeks. Fragipan Upland Flatwoods occur in depressional areas within broader areas of Fragipan Upland Woodland. Low-base Chert Upland Woodland sites are often directly downslope. Soils have root-restricting fragipans. The reference plant community is woodland with an overstory dominated by post oak and black oak and a ground flora of native grasses and forbs.

Associated sites

| F116BY003MO |

Chert Upland Woodland Chert Upland Woodlands are often downslope. |

|---|---|

| F116BY004MO |

Low-Base Chert Upland Woodland Low-base Chert Upland Woodlands are often downslope. |

| F116BY010MO |

Low-Base Chert Protected Backslope Woodland Low-base Chert Protected Backslope Woodlands are often downslope, on steep northern and eastern aspects. |

| F116BY033MO |

Low-Base Chert Exposed Backslope Woodland Low-base Chert Exposed Backslope Woodlands are often downslope, on steep southern and western aspects. |

| R116BY021MO |

Chert Upland Prairie In the western part of the Fragipan Upland Woodlands range, Chert Upland Prairie sites are often slightly higher, on broad prairie surfaces. |

Similar sites

| F116BY039MO |

Fragipan Upland Flatwoods Fragipan Upland Flatwoods are on the flattest upland positions. Extensive ponding in the spring occurs. These sites are less productive. |

|---|

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

(1) Quercus stellata |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Rhus aromatica |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Schizachyrium scoparium |

Physiographic features

This site is on level to broadly convex upland summits that include broad shallow depressions in some areas. Slopes range from 1 to 8 percent. The site generates runoff to adjacent, downslope ecological sites. This site does not flood.

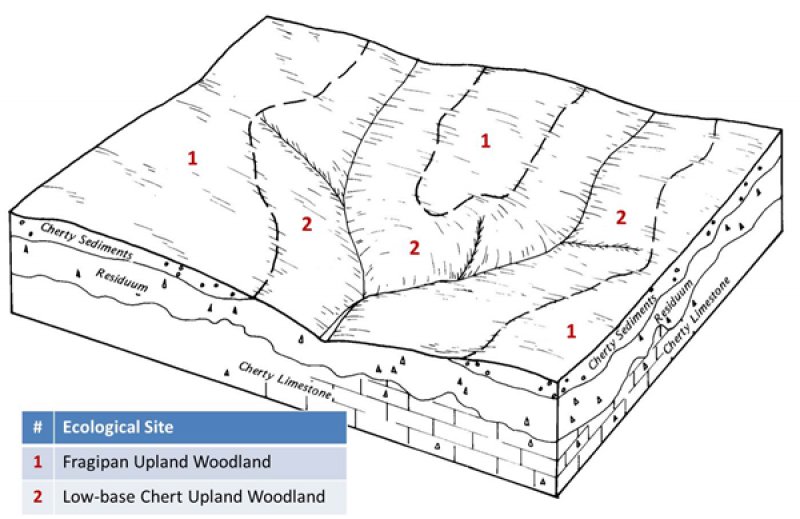

The following figure (adapted from Aldrich, 1989) shows the typical landscape position of this ecological site, and landscape relationships with other ecological sites. The site is within the area labeled “1”, on broadly convex upland summits. Low-base Chert Upland Woodland sites are often directly downslope, and are included within the area labeled “2”.

Figure 2. Landscape relationships for this ecological site.

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Interfluve

(2) Ridge (3) Depression |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Slope | 1 – 8% |

| Water table depth | 7 – 27 in |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The Springfield Plain has a continental type of climate marked by strong seasonality. In winter, dry-cold air masses, unchallenged by any topographic barriers, periodically swing south from the northern plains and Canada. If they invade reasonably humid air, snowfall and rainfall result. In summer, moist, warm air masses, equally unchallenged by topographic barriers, swing north from the Gulf of Mexico and can produce abundant amounts of rain, either by fronts or by convectional processes.

In some summers, high pressure stagnates over the region, creating extended droughty periods. Spring and fall are transitional seasons when abrupt changes in temperature and precipitation may occur due to successive, fast-moving fronts separating contrasting air masses.

The Springfield Plain experiences some regional differences in climates. The average annual precipitation in this area is 41 to 45 inches. Snow falls nearly every winter, but the snow cover lasts for only a few days. The average annual temperature is about 55 to 58 degrees F. The lower temperatures occur at the higher elevations. Mean July maximum temperatures have a range of only one or two degrees across the area.

Mean annual precipitation varies along a west to east gradient. Seasonal climatic variations are more complex. Seasonality in precipitation is very pronounced due to strong continental influences. June precipitation, for example, averages three to four times greater than January precipitation. Most of the rainfall occurs as high-intensity, convective thunderstorms in summer.

During years when precipitation is normal, moisture is stored in the soil profile during the winter and early spring, when evaporation and transpiration are low. During the summer months the loss of water by evaporation and transpiration is high, and if rainfall fails to occur at frequent intervals, drought will result. Drought directly affects plant and animal life by limiting water supplies, especially at times of high temperatures and high evaporation rates. Drought indirectly affects ecological communities by increasing plant and animal susceptibility to the probability and severity of fire. Frequent fires encourage the development of grass/forb dominated communities and understories.

Superimposed upon the basic MLRA climatic patterns are local topographic influences that create topoclimatic, or microclimatic variations. In regions of appreciable relief, for example, air drainage at nighttime may produce temperatures several degrees lower in valley bottoms than on side slopes. At critical times during the year, this phenomenon may produce later spring or earlier fall freezes in valley bottoms. Deep sinkholes often have a microclimate significantly cooler, moister, and shadier than surrounding surfaces that may result in a strikingly different vegetational composition and community structure. Higher daytime temperatures of bare rock surfaces and higher reflectivity of these unvegetated surfaces create characteristic glade and cliff ecological sites. Slope orientation is an important topographic influence on climate. Summits and south-and-west-facing slopes are regularly warmer and drier than adjacent north- and-east-facing slopes. Finally, the climate within a canopied forest ecological site is measurably different from the climate of the more open grassland or savanna ecological sites.

Source: University of Missouri Climate Center - http://climate.missouri.edu/climate.php;

Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin, United States Department of Agriculture Handbook 296 - http://soils.usda.gov/survey/geography/mlra/

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (characteristic range) | 149-162 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (characteristic range) | 185-192 days |

| Precipitation total (characteristic range) | 46-47 in |

| Frost-free period (actual range) | 143-162 days |

| Freeze-free period (actual range) | 182-194 days |

| Precipitation total (actual range) | 46-48 in |

| Frost-free period (average) | 155 days |

| Freeze-free period (average) | 188 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 46 in |

Figure 3. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 4. Monthly minimum temperature range

Figure 5. Monthly maximum temperature range

Figure 6. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 7. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 8. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) STOCKTON DAM [USC00238082], Stockton, MO

-

(2) SPRINGFIELD [USW00013995], Springfield, MO

-

(3) NEOSHO [USC00235976], Neosho, MO

Influencing water features

This ecological site is not influenced by wetland or riparian water features. However, a seasonal zone of saturation occurs, perched on the fragipan in the subsoil. In broad depressional areas within this site, seasonal wetness and ponding can occur, resulting in a flatwoods woodland community on sites. Where present, these depressional areas are in the MINERAL FLAT class in the Hydrogeomorphic (HGM) system (Brinson, 1993), and are Forested Palustrine wetlands (Cowardin et al., 1979).

Soil features

These soils have a root-restricting fragipan at about 24 inches. The soils were formed under woodland vegetation, and have thin, light-colored surface horizons. They have silt loam surface horizons, and silty clay loam subsoils. Soil materials in and below the fragipan may be very gravelly. Parent material is a thin layer of loess over residuum derived primarily from cherty limestone. These soils are affected by seasonal wetness in spring months from a water table perched on the fragipan. Soil series associated with this site include Captina, Hobson, Tonti, and Viraton.

The accompanying picture of the Tonti series shows a thin, light-colored surface horizon and reddish brown gravelly silt loam subsoil, over a fragipan at about 60 cm. The fragipan is a barrier to roots. Scale is in centimeters. Picture courtesy of John Preston, NRCS.

Figure 9. Tonti series

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Residuum

–

limestone

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Silt loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Moderately well drained |

| Permeability class | Very slow |

| Soil depth | 16 – 30 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | Not specified |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | Not specified |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

4 – 6 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

Not specified |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

4.5 – 6 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

5 – 50% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

5% |

Ecological dynamics

Information contained in this section was developed using historical data, professional experience, field reviews, and scientific studies. The information presented is representative of very complex vegetation communities. Key indicator plants, animals and ecological processes are described to help inform land management decisions. Plant communities will differ across the MLRA because of the naturally occurring variability in weather, soils, and aspect. The Reference Plant Community is not necessarily the management goal. The species lists are representative and are not botanical descriptions of all species occurring, or potentially occurring, on this site. They are not intended to cover every situation or the full range of conditions, species, and responses for the site.

Historically, Fragipan Upland Woodlands were dominated by drought and fire-tolerant post and blackjack oaks. Their landscape position and juxtaposition to prairies lead to a high fire frequency (every 1 to 3 years). These woodlands ranged from savannas near the prairie edge to open, park-like woodlands farther away. Canopy closure varied from 40 to 70 percent and tree height from 35 to 50 feet.

Native prairie grasses dominated the open understory, along with a diverse mix of native legumes, asters, sunflowers and other forbs. Dense thickets of oak sprouts occurred during periods of less-frequent fire, but periodic fire would eventually clear them out. Grazing by native large herbivores, such as bison, elk, and white-tailed deer also influenced the understory, keeping it more open and structurally diverse.

Today, this community has been cleared and converted to pasture, or has grown dense in the absence of fire. Most occurrences exhibit canopy closure of 80 to 100 percent. In addition, the sub-canopy and understory layers are more developed. Post oak and black oak share dominance with black hickory and an occasional white oak. Under these denser, more shaded conditions, the original sun-loving ground flora has diminished in diversity and cover. While some woodland species persist in the ground flora, many have been replaced by more shade-tolerant species.

Uncontrolled domestic grazing has also impacted these communities, further diminishing the diversity of native plants and introducing invasive species that are tolerant of grazing, such as coralberry, gooseberry, Virginia creeper and, in severely overgrazed situations, mosses and lichens.

Although timber products from these woodlands are of limited value, logging does occur, and influences the community. Occasional partial cuts provide sunlight to the woodland floor, stimulating native woodland ground flora. However, in the absence of fire and continual cultural treatments, oaks sprout and grow into a dense stand, again shading out the sun-loving ground flora.

Partial cutting and prescribed fire can, however, restore the more open structure and diversity of ground flora species. Managed areas show an exceptional resiliency. This type of management may provide timber products, wildlife habitat, and potential native forage.

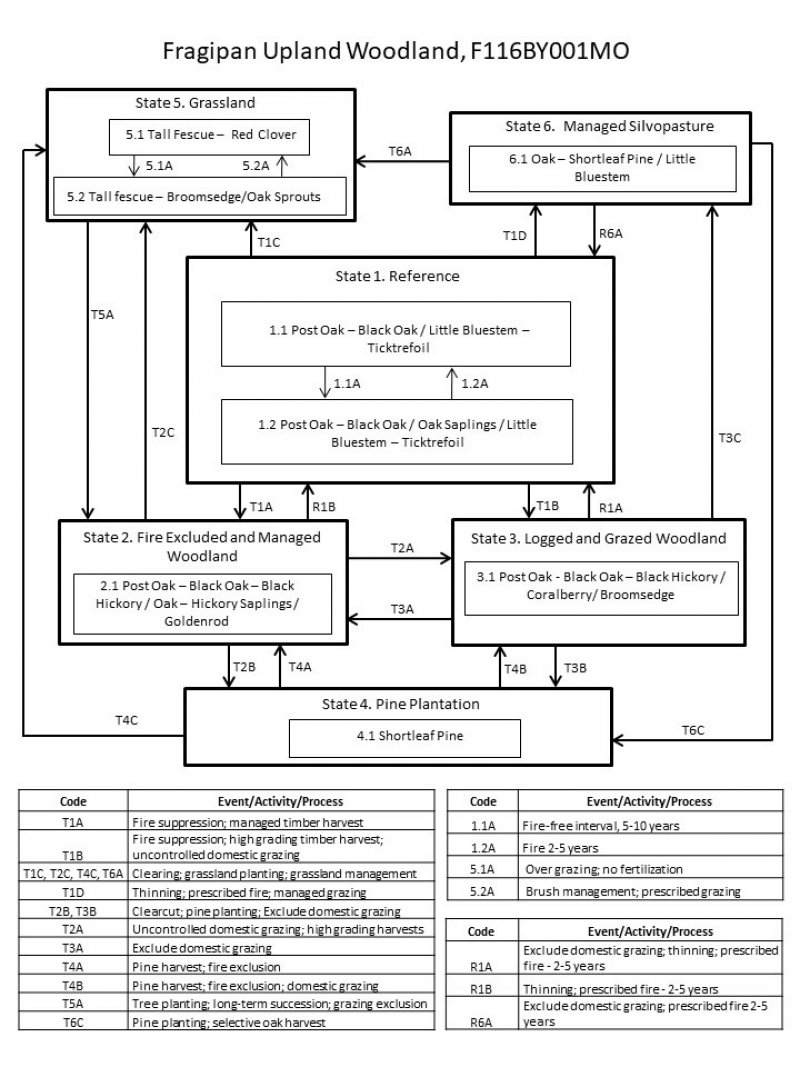

A State and Transition Diagram follows. Detailed descriptions of each state, transition, plant community, and pathway follow the model. This model is based on available experimental research, field observations, professional consensus, and interpretations. It is likely to change as knowledge increases.

State and transition model

Figure 10. State and Transition Model for this ecological site.

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

States 1, 5 and 6 (additional transitions)

States 2 and 5 (additional transitions)

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 5 submodel, plant communities

State 6 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference

These open woodland communities were strongly influenced by fire. Herbivory by native (now expatriated) ungulates also played a role. Consequently, this maintained drought and fire-tolerant post, black and blackjack oaks over a ground flora of tallgrass prairie grasses, sedges and wildflowers. There are two phases associated with this Reference State.

Community 1.1

Post Oak – Blackjack Oak /Little Bluestem - Ticktrefoil

The overstory in this phase is dominated by post oak and blackjack oak, with black oak and black hickory also present. This open woodland community typically has a two-tiered structure, with canopy height of 40 to 60 feet and 40 to 70 percent closure. The abundant herbaceous layer is dominated by little bluestem, big bluestem and Indiangrass. Fire frequency was every 1 to 3 years. This continued fire would have maintained the more open canopy and profusion of ground flora species. Herbivory by native (now expatriated) ungulates also played a role.

Forest overstory. The overstory is dominated by post oak and blackjack oak, with scattered black oak and black hickory. The Overstory Species list is based on field reconnaissance as well as commonly occurring species listed in Nelson 2010; names and symbols are from USDA PLANTS database.

Forest understory. The abundant understory layer is dominated by little bluestem, big bluestem and Indiangrass. Forbs are common. The Understory Species list is based on field reconnaissance as well as commonly occurring species listed in Nelson 2010; names and symbols are from USDA PLANTS database.

Community 1.2

Post Oak – Blackjack Oak / Oak Saplings / Little Bluestem - Ticktrefoil

This phase is similar to community phase 1.1. Due to fire-free intervals that likey ranged from 5 to 10 years, this brushy woodland community typically has a three-tiered structure, with 50 to 80 percent closure. It is characterized by a thick understory of oak saplings, and shrubs. The herbaceous layer is dominated by little bluestem.

Forest overstory. The overstory is dominated by post oak and blackjack oak, with scattered black oak and black hickory.

Forest understory. It is characterized by a thick understory of oak saplings, and shrubs. The herbaceous layer is dominated by little bluestem.

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

This pathway is a gradual transition that results from fire-free periods of roughly 3 to 10 years or longer.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

This pathway results from fire. Historically, native grazers such as bison provided understory disturbance as well.

State 2

Fire Excluded and Managed Woodland

Most current areas of Fragipan Upland Woodlands have suffered fire exclusion for decades. In the absence of fire, ongoing recruitment of trees develops into a closed canopy, shading out the rich herbaceous ground flora. This results in the formation of the post oak, black oak, black hickory closed woodland. Black oak and white oak increase in the canopy. Herbaceous cover and diversity greatly diminishes, leaf litter builds up, and only a few shade-tolerant woodland species persist, such as elmleaf goldenrod, panicgrass and spreading aster. The understory also develops with oak and hickory saplings along with sassafras and black cherry. Single-tree timber harvest often occurs, resulting in a stimulation of understory saplings and herbaceous vegetation. However, without fire, the reference species richness and open structure do not return.

Dominant resource concerns

-

Plant productivity and health

-

Plant structure and composition

-

Terrestrial habitat for wildlife and invertebrates

Community 2.1

Post Oak – Black Oak – Black Hickory/Oak-Hickory Saplings/Goldenrod

Figure 11. Fragilpan Upland Woodland restoration at the Fuson Conservation Area, Missouri

This phase is dominated by post oak, black oak, and black hickory. Scattered blackjack oak and white oak occur in the canopy as well. This closed woodland community has a multi-tiered structure, with 80 to 100 percent canopy closure.

State 3

Logged and Grazed Woodland

Although many of the closed Fragipan Upland Woodlands are now fenced, most have been heavily grazed by domestic livestock at some point in their history. Grazing decreases the cover and abundance of saplings, shrubs and herbaceous ground flora, opening up the understory. Weedy native shrubs and vines, such as coralberry, gooseberry, poison ivy and Virginia creeper, often flourish after grazing, and exotic species like tall fescue and sericea lespedeza increase in abundance. Poorly managed grazing can cause compaction and denudation of the soil surface, allowing mats of lichens and mosses to flourish. Soil compaction may also further limit height growth of trees. With poorly managed grazing, this can result in an increase in weedy natives such as broomsedge, and exotics such as sericea lespedeza if they are present. Single-tree timber harvesting also occurred, resulting in a high grading of the canopy structure, creating many stands with poorly formed trees.

Dominant resource concerns

-

Sheet and rill erosion

-

Ephemeral gully erosion

-

Nutrients transported to surface water

-

Plant productivity and health

-

Plant structure and composition

-

Plant pest pressure

-

Wildfire hazard from biomass accumulation

-

Terrestrial habitat for wildlife and invertebrates

Community 3.1

Post Oak – Black Oak – Black Hickory / Buckbrush / Broomsedge

The overstory is dominated by post oak, black oak, and black hickory. Scattered blackjack oak and white oak occur in the canopy as well. This closed woodland community has a two to three-tiered structure, and a 80 to 100 percent canopy closure. The understory includes weedy native shrubs and vines, such as buckbrush, gooseberry, poison ivy and Virginia creeper. Mats of lichens and mosses occur on areas denuded by livestock.

State 4

Pine Plantation

The Pine Plantation state results from clearing the oak woodlands and planting shortleaf pine. Shortleaf pine grows well on less-productive sites, so the practice was common during reforestation of the Ozarks in the middle of the 20th century. The plantations are typically dense, mature stands of pine with deep leaf litter and little understory or groundflora vegetation. A return from this condition to a woodland state requires enormous energy inputs.

Dominant resource concerns

-

Plant structure and composition

-

Terrestrial habitat for wildlife and invertebrates

Community 4.1

Shortleaf Pine

The plantations are typically dense, mature stands of pine with deep leaf litter and little groundflora vegetation. They have a two-tiered structure, with canopy height of about 45 to 60 feet and canopy closures of 80 to 100 percent.

State 5

Grassland

Conversion of these woodlands to planted, non-native grassland species such as tall fescue and red clover has been common occurrence. Clearing is often done by bulldozing. This practice often strips the thin topsoil along with most of the native ground cover plants. Occasionally, clumps of trees will be left in small groves for shade, giving the structural appearance of historic woodlands. However, Fragipan Upland Woodlands have most often been converted into wide, open fescue grasslands, adjacent to densely overgrown and grazed woodlots. A return from this condition to a reference state requires enormous cost and management inputs.

Community 5.1

Tall Fescue - Red Clover

This is an herbaceous community that is typically dominated by tall fescue. Various other grass and forb species are typically present, in various amounts. Shrub and pioneer tree species such as eastern redcedar and black locust along with oak sprouts typically invade sites that are not regularly managed.

Dominant resource concerns

-

Terrestrial habitat for wildlife and invertebrates

Community 5.2

Tall Fescue - Broomsedge/Oak Sprouts

Dominant resource concerns

-

Sheet and rill erosion

-

Ephemeral gully erosion

-

Nutrients transported to surface water

-

Plant productivity and health

-

Plant structure and composition

-

Plant pest pressure

-

Terrestrial habitat for wildlife and invertebrates

-

Feed and forage imbalance

Pathway P5.1A

Community 5.1 to 5.2

Over grazing; no fertilization

Pathway P5.2A

Community 5.2 to 5.1

Brush management; prescribed grazing; grassland management

State 6

Managed Silvopasture

Although this state is currently uncommon, Fragipan Upland Woodlands have the potential to support controlled grazing while maintaining a near-reference composition and structure. Short periods of rotational grazing, especially during the hot, dry summer season, along with thinning and prescribed fire, has the potential to create an open, diverse woodland with abundant native forage. Controlled grazing may emulate historical grazing by native herbivores and create a structural diversity in the ground flora that may be beneficial to ground-nesting birds.

Community 6.1

Oak-Shortleaf Pine/Little Bluestem

This phase has an open, two-tiered structure of post oak and shortleaf pine over native grasses and forbs. Canopy height is typically 40 to 60 feet, with canopy closure of 20 to 60 percent. Native grasses include little bluestem, big bluestem and Indian grass.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Fire suppression; managed timber harvest

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

This transition results from fire suppression combined with timber harvests and domestic grazing.

Transition T1C

State 1 to 5

This transition is the result of clearing the woodland community and planting pasture species. Topsoil can be relocated to bulldozed burn piles or lost to erosion in this process, along with loss of organic matter. Liming and fertilizing associated with pasture management typically raises the soil pH and increases the cation concentration (such as calcium and magnesium) of the upper soil horizons.

Transition T1D

State 1 to 6

This transition is the result of thinning the canopy species, combined with prescribed fire and well-managed domestic grazing.

Restoration pathway R1B

State 2 to 1

Thinning; prescribed fire every 2-5 years

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

This transition is the result of poorly managed domestic grazing and timber harvesting.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 4

This transition is the result of clearcutting the hardwood canopy species and planting shortleaf pine.

Transition T2C

State 2 to 5

This transition is the result of clearing the woodland community and planting pasture species. Topsoil can be relocated to bulldozed burn piles or lost to erosion in this process, along with loss of organic matter. Liming and fertilizing associated with pasture management typically raises the soil pH and increases the cation concentration (such as calcium and magnesium) of the upper soil horizons.

Restoration pathway R1A

State 3 to 1

Exclude domestic grazing; thinning; prescribed fire - 2-5 years; long rotations of 70-80 years.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 2

This transition results from the exclusion of domestic grazing and forest stand improvement.

Transition T3B

State 3 to 4

This transition is the result of clearcutting the hardwood canopy species and planting shortleaf pine.

Transition T3C

State 3 to 6

This transition is the result of planting shortleaf pine, combined with prescribed fire and well-managed domestic grazing.

Transition T4A

State 4 to 2

This transition results from clearcut harvest of the shortleaf pine, combined with fire exclusion and long-term succession.

Transition T4B

State 4 to 3

This transition results from clearcut harvest of the shortleaf pine, combined with fire exclusion and long-term succession, under the influence of domestic grazing.

Transition T4C

State 4 to 5

This transition is the result of clearing the pine community and planting pasture species. Topsoil can be relocated to bulldozed burn piles or lost to erosion in this process, along with loss of organic matter. Liming and fertilizing associated with pasture management typically raises the soil pH and increases the cation concentration (such as calcium and magnesium) of the upper soil horizons.

Transition T5A

State 5 to 2

This transition results from the cessation of cattle grazing and associated pasture management such as mowing and brush-hogging. Herbicide application, tree planting and timber stand improvement techniques can speed up this otherwise very lengthy transition.

Restoration pathway R6A

State 6 to 1

Exclude domestic grazing; prescribed fire 2-5 years; long rotations of 70-80 years.

Transition T6B

State 6 to 3

This transition results from fire suppression.

Transition T6C

State 6 to 4

This transition results from planting shortleaf pine.

Transition T6A

State 6 to 5

This transition is the result of clearing the woodland community and planting pasture species. Topsoil can be relocated to bulldozed burn piles or lost to erosion in this process, along with loss of organic matter. Liming and fertilizing associated with pasture management typically raises the soil pH and increases the cation concentration (such as calcium and magnesium) of the upper soil horizons.

Additional community tables

Table 5. Community 1.1 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (ft) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (in) | Basal area (square ft/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| post oak | QUST | Quercus stellata | Native | – | 10–30 | – | – |

| blackjack oak | QUMA3 | Quercus marilandica | Native | – | 10–30 | – | – |

| black hickory | CATE9 | Carya texana | Native | – | 10–30 | – | – |

| black oak | QUVE | Quercus velutina | Native | – | 10–30 | – | – |

| sassafras | SAAL5 | Sassafras albidum | Native | – | 0–10 | – | – |

| shortleaf pine | PIEC2 | Pinus echinata | Native | – | 0–10 | – | – |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | – | 0–10 | – | – |

Table 6. Community 1.1 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (ft) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| poverty oatgrass | DASP2 | Danthonia spicata | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| hirsute sedge | CACO9 | Carex complanata | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| blue sedge | CAGL6 | Carex glaucodea | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| Virginia wildrye | ELVI3 | Elymus virginicus | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| broomsedge bluestem | ANVI2 | Andropogon virginicus | Native | – | 5–20 | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| smooth small-leaf ticktrefoil | DEMA2 | Desmodium marilandicum | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| panicledleaf ticktrefoil | DEPA6 | Desmodium paniculatum | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| slender lespedeza | LEVI7 | Lespedeza virginica | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| sidebeak pencilflower | STBI2 | Stylosanthes biflora | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| queendevil | HIGR3 | Hieracium gronovii | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| hairy sunflower | HEHI2 | Helianthus hirsutus | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| largeflower yellow false foxglove | AUGR | Aureolaria grandiflora | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| white wild indigo | BAAL | Baptisia alba | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| elmleaf goldenrod | SOUL2 | Solidago ulmifolia | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| common cinquefoil | POSI2 | Potentilla simplex | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| Virginia tephrosia | TEVI | Tephrosia virginiana | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| stiff tickseed | COPA10 | Coreopsis palmata | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| pussytoes | ANTEN | Antennaria | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| American hogpeanut | AMBR2 | Amphicarpaea bracteata | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| slender lespedeza | LEVI7 | Lespedeza virginica | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| flowering spurge | EUCO10 | Euphorbia corollata | Native | – | 5–20 | |

|

Shrub/Subshrub

|

||||||

| fragrant sumac | RHAR4 | Rhus aromatica | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| New Jersey tea | CEAM | Ceanothus americanus | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| American hazelnut | COAM3 | Corylus americana | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| black huckleberry | GABA | Gaylussacia baccata | Native | – | 5–20 | |

Table 7. Community 1.2 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (ft) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (in) | Basal area (square ft/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| post oak | QUST | Quercus stellata | Native | – | 40–60 | – | – |

| blackjack oak | QUMA3 | Quercus marilandica | Native | – | 30–50 | – | – |

| black hickory | CATE9 | Carya texana | Native | – | 20–40 | – | – |

| black oak | QUVE | Quercus velutina | Native | – | 20–30 | – | – |

| sassafras | SAAL5 | Sassafras albidum | Native | – | 0–20 | – | – |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | – | 5–20 | – | – |

Table 8. Community 1.2 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (ft) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | Native | – | 20–60 | |

| poverty oatgrass | DASP2 | Danthonia spicata | Native | – | 20–40 | |

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | Native | – | 10–30 | |

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | Native | – | 10–30 | |

| Virginia wildrye | ELVI3 | Elymus virginicus | Native | – | 10–20 | |

| broomsedge bluestem | ANVI2 | Andropogon virginicus | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| hirsute sedge | CACO9 | Carex complanata | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| blue sedge | CAGL6 | Carex glaucodea | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| Leiberg's panicum | DILE2 | Dichanthelium leibergii | Native | – | 5–10 | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| stiff tickseed | COPA10 | Coreopsis palmata | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| largeflower yellow false foxglove | AUGR | Aureolaria grandiflora | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| slender lespedeza | LEVI7 | Lespedeza virginica | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| pussytoes | ANTEN | Antennaria | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| smooth small-leaf ticktrefoil | DEMA2 | Desmodium marilandicum | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| panicledleaf ticktrefoil | DEPA6 | Desmodium paniculatum | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| American hogpeanut | AMBR2 | Amphicarpaea bracteata | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| sidebeak pencilflower | STBI2 | Stylosanthes biflora | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| hairy hawkweed | HILO2 | Hieracium longipilum | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| trailing lespedeza | LEPR | Lespedeza procumbens | Native | – | 5–10 | |

|

Shrub/Subshrub

|

||||||

| New Jersey tea | CEAM | Ceanothus americanus | Native | – | 0–20 | |

| American hazelnut | COAM3 | Corylus americana | Native | – | 0–20 | |

| black huckleberry | GABA | Gaylussacia baccata | Native | – | 0–20 | |

| fragrant sumac | RHAR4 | Rhus aromatica | Native | – | 0–20 | |

Table 9. Community 2.1 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (ft) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (in) | Basal area (square ft/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| black hickory | CATE9 | Carya texana | Native | – | 20–30 | – | – |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | – | 10–30 | – | – |

| post oak | QUST | Quercus stellata | Native | – | 20–30 | – | – |

| black oak | QUVE | Quercus velutina | Native | – | 20–30 | – | – |

| sassafras | SAAL5 | Sassafras albidum | Native | – | 10–20 | – | – |

| rusty blackhaw | VIRU | Viburnum rufidulum | Native | – | 10–20 | – | – |

| black cherry | PRSE2 | Prunus serotina | Native | – | 5–20 | – | – |

| blackjack oak | QUMA3 | Quercus marilandica | Native | – | 5–20 | – | – |

| eastern redcedar | JUVI | Juniperus virginiana | Native | – | 5–20 | – | – |

Table 10. Community 2.1 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (ft) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | Native | – | 5–20 | |

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | Native | – | 0–10 | |

| poverty oatgrass | DASP2 | Danthonia spicata | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| Leiberg's panicum | DILE2 | Dichanthelium leibergii | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| Virginia wildrye | ELVI3 | Elymus virginicus | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | Native | – | 0–10 | |

| broomsedge bluestem | ANVI2 | Andropogon virginicus | Native | – | 0–5 | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| elmleaf goldenrod | SOUL2 | Solidago ulmifolia | Native | – | 10–20 | |

| pussytoes | ANTEN | Antennaria | Native | – | 0–10 | |

| slender lespedeza | LEVI7 | Lespedeza virginica | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| smooth small-leaf ticktrefoil | DEMA2 | Desmodium marilandicum | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| panicledleaf ticktrefoil | DEPA6 | Desmodium paniculatum | Native | – | 5–10 | |

|

Shrub/Subshrub

|

||||||

| fragrant sumac | RHAR4 | Rhus aromatica | Native | – | 0–10 | |

|

Vine/Liana

|

||||||

| Virginia creeper | PAQU2 | Parthenocissus quinquefolia | Native | – | 0–10 | |

Table 11. Community 3.1 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (ft) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (in) | Basal area (square ft/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| post oak | QUST | Quercus stellata | Native | – | 20–40 | – | – |

| black oak | QUVE | Quercus velutina | Native | – | 10–40 | – | – |

| blackjack oak | QUMA3 | Quercus marilandica | Native | – | 10–30 | – | – |

| black hickory | CATE9 | Carya texana | Native | – | 10–30 | – | – |

| eastern redcedar | JUVI | Juniperus virginiana | Native | – | 0–20 | – | – |

| black cherry | PRSE2 | Prunus serotina | Native | – | 0–10 | – | – |

| white oak | QUAL | Quercus alba | Native | – | 5–10 | – | – |

| sassafras | SAAL5 | Sassafras albidum | Native | – | 0–10 | – | – |

Table 12. Community 3.1 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (ft) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| broomsedge bluestem | ANVI2 | Andropogon virginicus | Native | – | 10–30 | |

| poverty oatgrass | DASP2 | Danthonia spicata | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| Virginia wildrye | ELVI3 | Elymus virginicus | Native | – | 5–10 | |

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | Native | – | 5–10 | |

|

Forb/Herb

|

||||||

| sericea lespedeza | LECU | Lespedeza cuneata | Introduced | – | 10–30 | |

| pussytoes | ANTEN | Antennaria | Native | – | 0–5 | |

| slender lespedeza | LEVI7 | Lespedeza virginica | Native | – | 0–5 | |

|

Shrub/Subshrub

|

||||||

| buckbrush | CECU | Ceanothus cuneatus | Native | – | 10–50 | |

| eastern prickly gooseberry | RICY | Ribes cynosbati | Introduced | – | 10–30 | |

| fragrant sumac | RHAR4 | Rhus aromatica | Native | – | 5–10 | |

|

Tree

|

||||||

| black cherry | PRSE2 | Prunus serotina | Native | – | 0–5 | |

|

Vine/Liana

|

||||||

| eastern poison ivy | TORA2 | Toxicodendron radicans | Native | – | 10–30 | |

| Virginia creeper | PAQU2 | Parthenocissus quinquefolia | Native | – | 10–20 | |

Table 13. Community 4.1 forest overstory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (ft) | Canopy cover (%) | Diameter (in) | Basal area (square ft/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tree

|

|||||||

| shortleaf pine | PIEC2 | Pinus echinata | Native | – | 80–100 | – | – |

Table 14. Community 4.1 forest understory composition

| Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Nativity | Height (ft) | Canopy cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/grass-like (Graminoids)

|

||||||

| broomsedge bluestem | ANVI2 | Andropogon virginicus | Native | – | 0–10 | |

| poverty oatgrass | DASP2 | Danthonia spicata | Native | – | 0–5 | |

| Virginia wildrye | ELVI3 | Elymus virginicus | Native | – | 0–5 | |

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | Native | – | 0–5 | |

Interpretations

Animal community

Wildlife (MDC, 2006):

Oaks provide hard mast; numerous native legumes provide high-quality wildlife food; native warm-season grasses provide extensive cover and nesting habitat; and forbs provide a diversity and abundance of insects.

Bird species associated with early-successional Upland Flatwoods are Northern Bobwhite, Painted Bunting, Prairie Warbler, Field Sparrow, Blue-winged Warbler, Yellow-breasted Chat, Brown Thrasher, and Bachman’s Sparrow. All of these species also occur in glades associated with woodlands. Birds associated with mid- to late successional sites [˜ 80+ years]) are Indigo Bunting, Red-headed Woodpecker, Eastern Bluebird, Northern Bobwhite, Summer Tanager, Eastern Wood-Pewee, Whip-poor-will, Chuck-will’s widow, and Red-eyed Vireo.

Reptiles and amphibians associated with Post Oak Woodlands include ornate box turtle, northern fence lizard, five-lined skink, coal skink, broad-headed skink, six-lined racerunner, western slender glass lizard, prairie ring-necked snake, flat-headed snake, rough earth snake, red milk snake, western pygmy rattlesnake, and timber rattlesnake.

Other information

Forestry (NRCS 2002; 2014):

Management: Field measured site index values average 50 for white oak and post oak, 56 for shortleaf pine, and 62 for black oak. Timber management opportunities are fair. These sites have a root-restricting fragipan which impedes rooting. Reduced rooting depth restricts tree growth and increases windthrow hazards. These sites respond well to prescribed fire as a management tool.

Limitations: Restricted rooting depth; seasonal wetness. Unsurfaced roads and traffic areas tend to be slippery and form ruts easily when wet. Graveling roads facilitates year-round use. Equipment use when wet may compact soil and damage tree roots. Planting is difficult during wet spring periods. Seedling mortality may be high due to excess seasonal wetness, shallow effective rooting depths or sodium. Ridging the soil and planting on the ridges may increase survival. The use of equipment can become restricted in spring and other excessively wet periods.

Table 15. Representative site productivity

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Potential Reference Sites: Fragipan Upland Woodland

Plot COHOCA01 – Captina soil

Located in Compton Hollow CA, Webster County, MO

Latitude: 37.23433

Longitude: -93.00144

Other references

Aldrich, M. W. 1989. Soil Survey of Newton County, Missouri. U.S. Dept. of Agric. Soil Conservation Service.

Anderson, R.C. 1990. The historic role of fire in North American grasslands. Pp. 8-18 in S.L. Collins and L.L. Wallace (eds.). Fire in North American tallgrass prairies. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Batek, M.J., A.J. Rebertus, W.A. Schroeder, T.L. Haithcoat, E. Compas, and R.P. Guyette. 1999. Reconstruction of early nineteenth-century vegetation and fire regimes in the Missouri Ozarks. Journal of Biogeography 26:397-412.

Brinson, M.M. 1993. A hydrogeomorphic classification for wetlands. Technical Report WRP-DE-4, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Waterways Experiment Station, Vicksburg, MS.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, & E.T. LaRoe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Dept. of Interior, Fish & Wildlife Service, Office of Biological Services, Washington DC.

Dodd, Jerry A. 1985. Soil Survey of Christian County, Missouri. U.S. Dept. of Agric. Soil Conservation Service.

Harlan, J.D., T.A. Nigh and W.A. Schroeder. 2001. The Missouri original General Land Office survey notes project. University of Missouri, Columbia.

Ladd, D. 1991. Reexamination of the role of fire in Missouri oak woodlands. Pp. 67-80 in G.V. Brown, James K.; Smith, Jane Kapler, eds. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on flora. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 2. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 257 p.

Missouri Department of Conservation. 2010. Missouri Forest and Woodland Community Profiles. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, Missouri.

Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2002. Woodland Suitability Groups. Missouri FOTG, Section II, Soil Interpretations and Reports. 30 pgs.

Natural Resources Conservation Service. Site Index Reports. Accessed May 2014. https://esi.sc.egov.usda.gov/ESI_Forestland/pgFSWelcome.aspx

NatureServe. 2010. Vegetation Associations of Missouri (revised). NatureServe, St. Paul, Minnesota.

Nelson, Paul W. 2010. The Terrestrial Natural Communities of Missouri. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, Missouri.

Nigh, Timothy A. and Walter A. Schroeder. 2002. Atlas of Missouri Ecoregions. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, Missouri.

Schoolcraft, H.R. 1821. Journal of a tour into the interior of Missouri and Arkansas from Potosi, or Mine a Burton, in Missouri territory, in a southwest direction, toward the Rocky Mountains: performed in the years 1818 and 1819. Richard Phillips and Company, London.

Taft, J. B., M.W. Schwartz and R.P. Loy. 1995. Vegetation ecology of flatwoods on the Illinoian till plain. Journal of Vegetation Science 6: 647-666.

United States Department of Agriculture – Natural Resource Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS). 2006. Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. U.S. Department of Agriculture Handbook 296. 682 pgs.

Contributors

Doug Wallace

Fred Young

Approval

Nels Barrett, 10/06/2020

Acknowledgments

Missouri Department of Conservation and Missouri Department of Natural Resources personnel provided significant and helpful field and technical support in the development of this ecological site.

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | |

| Date | 09/06/2022 |

| Approved by | Nels Barrett |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

-

Presence of water flow patterns:

-

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

-

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

-

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

-

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

-

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

-

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

-

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

-

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

-

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

-

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Sub-dominant:

Other:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

-

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

-

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

-

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.