Ecological site group R008XG630WA

Loamy, Grassland

Last updated: 09/21/2023

Accessed: 12/20/2025

Ecological site group description

Key Characteristics

None specified

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Physiography

A PROVISIONAL ECOLOGICAL SITE is a conceptual grouping of soil map unit components within a Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) based on the similarities in response to management. Although there may be wide variability in the productivity of the soils grouped into a Provisional Site, the soil vegetation interactions as expressed in the State and Transition Model are similar and the management actions required to achieve objectives, whether maintaining the existing ecological state or managing for an alternative state, are similar. Provisional Sites are likely to be refined into more precise group during the process of meeting the APPROVED ECOLOGICAL SITE DESCRIPTION criteria.

This PROVISIONAL ECOLOGICAL SITE has been developed to meet the standards established in the National Ecological Site Handbook. The information associated with this ecological site does not meet the Approved Ecological Site Description Standard, but it has been through a Quality Control and Quality Assurance processes to assure consistency and completeness. Further investigations, reviews and correlations are necessary before it becomes an Approved Ecological Site Description.

Hierarchical Classification

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 8 – Columbia Plateau

LRU – Common Resource Areas (CRA):

8.1 - Channeled Scablands

8.2 - Loess Islands

8.3 - Okanogan Drift Hills

8.6 - Lower Snake and Clearwater Canyons

Site Concept Narrative:

Note: For MLRA 8 there are four ecological sites with the name ‘Loamy’.

1. One for the sagebrush steppe region

2. One specifically for grasslands on Goldendale Prairie (Klickitat Co.)

3. One specifically for grasslands on south side of Columbia Hills (Klickitat Co.)

4. One for other grassland regions in MLRA 8 including

a. SE portion of MLRA 8 includes portions of Adams, Franklin, Walla Walla, Asotin, Columbia and Garfield counties

b. Elevations above 2400 feet in northern Douglas Co. including Dyer Hill and Wilson Butte

The ESD below is for other grassland areas in MLRA 8 including portions of Adams, Franklin, Walla, Walla, Asotin, Columbia, Garfield and Douglas counties (see 4a and 4b above).

Diagnostics:

Loamy, grassland ESD is an upland site occurring on 20 inches and deeper loamy soils on other grassland regions of MLRA 8. Soils have a loamy to sandy loam surface texture and limited rock fragments (generally 10% or less) in the root-growing portions of the soil profile. Silt loam soils are most common, but a variety of soils and landforms are possible.

Loamy, grassland is found on flat areas and west, east and south slopes.

Grassland steppe areas have not had sagebrush or bitterbrush for more than 50 years and are not expected to have either. Perennial bunchgrasses dominate the reference state. Fire-tolerant shrubs are a minor presence in the reference state, while forbs fill the interspaces. The shrub layer is typically knee- to waist-high rabbitbrush. Cool-season bunchgrasses form two distinct layers. Bluebunch wheatgrass is the dominant bunchgrass in the top grass layer, while Sandberg bluegrass is the major grass of the lower grass layer.

Principle Vegetative Drivers:

The moderately deep to deep silt loam soils drive the vegetative expression of this productive site. Most species have unrestricted rooting on this site.

Influencing Water Features:

A plant’s ability to grow on a site and overall plant production is determined by soil-water-plant relationships

1. Whether rain and melting snow runs off-site or infiltrates into the soil

2. Whether soil condition remain aerobic or become saturated and become anaerobic

3. Water drainage and how quickly the soil reaches wilting point

The Loamy, grassland site consists of deep soils and occurs for the most part on gently sloping landforms with little limitations for water infiltration. On steeper slopes and localized high silt or sodic soils, infiltration may be limited. Calcic and petrocalcic horizons may be present indicating long-term moisture penetration. There is generally no run-in moisture from surrounding sites or long-term soil moisture saturation.

Physiographic Features:

The landscape is part of the Columbia basalt plateau. Loamy, grassland sites occur on broad ridges and plateaus, stream terraces, and east-facing hillslopes in Adams, Franklin, Walla, Walla, Asotin, Columbia, Garfield and Douglas counties

Physiographic Division: Intermontane Plateau

Physiographic Province: Columbia Plateau

Physiographic Sections: Walla Walla Plateau Section

Landscapes: Hills, valleys, scablands and plateaus

Landform: Sideslopes, terraces, till plain, ridges, alluvial fans

Elevation: Dominantly 800 to 4,000 feet

Central tendency: 1,200 to 3,000 feet

Slope: Total range: 0 to 65 percent

Central tendency: 2 to 30 percent

Aspect: Occurs on all aspects

Geology:

This MLRA is almost entirely underlain by Miocene basalt flows. Columbia River basalt is covered in many areas with as much as 200 feet of loess and volcanic ash. Small areas of sandstones, siltstones, and conglomerates of the Upper Tertiary Ellensburg Formation are along the western edge of this area. Some Quaternary glacial drift covers the northern edge of the basalt flows, and some Miocene-Pliocene continental sedimentary deposits occur south of the Columbia River, in Oregon.

A wide expanse of scablands in the eastern portion of this MLRA, in Washington, was deeply dissected about 16,000 years ago, when an ice dam that formed ancient glacial Lake Missoula was breached several times, creating catastrophic floods. The geology of the northernmost part of this MLRA is distinctly different from that of the rest of the area. Alluvium, glacial outwash, and glacial drift fill the valley floor of the Okanogan River and the side valleys of tributary streams. The fault parallel with the valley separates pre-Tertiary metamorphic rocks on the west, in the Cascades, from older, pre-Cretaceous metamorphic rocks on the east, in the Northern Rocky Mountains. Mesozoic and Paleozoic sedimentary rocks cover the metamorphic rocks for most of the length of the valley on the west.

Climate

Grasslands do not have shrubs because they receive more spring precipitation especially in March (Daubenmire). The climate is characterized by moderately cold, wet winters, and hot, dry summers, with limited precipitation due to the rain shadow effect of the Cascades. Taxonomic soil climate is either xeric (12 – 16 inches PPT) or aridic moisture regimes (10 – 12 inches PPT) with a mesic temperature regime.

Mean Annual Precipitation:

Range: 10 – 16 inches

Seventy to seventy-five percent of the precipitation comes late October through March as a mixture of rain and snow. June through early October is mostly dry.

Mean Annual Air Temperature:

Range: 46 to 54 F

Central Tendency: 48 – 52 F

Freezing temperatures generally occur from late-October through early-April. Temperature extremes are 0 degrees in winter and 110 degrees in summer. Winter fog is variable and often quite localized, as the fog settles on some areas but not others.

Frost-free Period (days):

Total range: 90 to 210

Central tendency: 110 to 160

The growing season for Loamy, grassland is March through mid-July.

Soil features

Edaphic:

The Loamy, grassland ecological site commonly occurs with Stony, Very Shallow, Cool Loamy and Loamy Bottom ecological sites.

Representative Soil Features:

This ecological site components are dominantly Typic, Aridic, Calcic, Calcidic and Vitrandic taxonomic subgroups of Haploxerolls, Haplocambids, Durixerolls and Haploxerepts great groups of the Mollisols, Aridisols and Inceptisols taxonomic orders. Soils are moderately deep to very deep. Average available water capacity of about 7.0 inches (17.8 cm) in the 0 to 40 inches (0-100 cm) depth range.

Soil parent material is dominantly mixed loess with influence of volcanic ash possible.

The associated soils are Asotin, Chard, Ellisforde, Farrell, Magallon, Nims, Ritzville, Roloff, Siweeka, Walla Walla and similar soils.

Dominate soil surface is silt loam to loam, with ashy modifier sometimes occurring as well.

Dominant particle-size class is fine-silty to coarse-loamy.

Fragments on surface horizon > 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 2

Average: 0

Fragments within surface horizon > 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 10

Average: 5

Fragments within surface horizon ≤ 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 20

Average: 5

Subsurface fragments > 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 30

Average: 10

Subsurface fragments ≤ 3 inches (% Volume):

Minimum: 5

Maximum: 40

Average: 10

Drainage Class: Dominantly well drained

Water table depth: Greater than 60 inches

Flooding:

Frequency: None

Ponding:

Frequency: None

Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity Class:

0 to 10 inches: High to moderately high

10 to 40 inches: High to moderately high

Depth to root-restricting feature (inches):

Minimum: 20

Maximum: Greater than 60 inches

Electrical Conductivity (dS/m):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 4

Sodium Absorption Ratio:

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 10

Calcium Carbonate Equivalent (percent):

Minimum: 0

Maximum: 30

Soil Reaction (pH) (1:1 Water):

0 - 10 inches: 5.6 to 9.0

10 - 40 inches: 5.6 to 9.6

Available Water Capacity (inches, 0 – 40 inches depth):

Minimum: 3.1

Maximum: 11.1

Average: 7.0

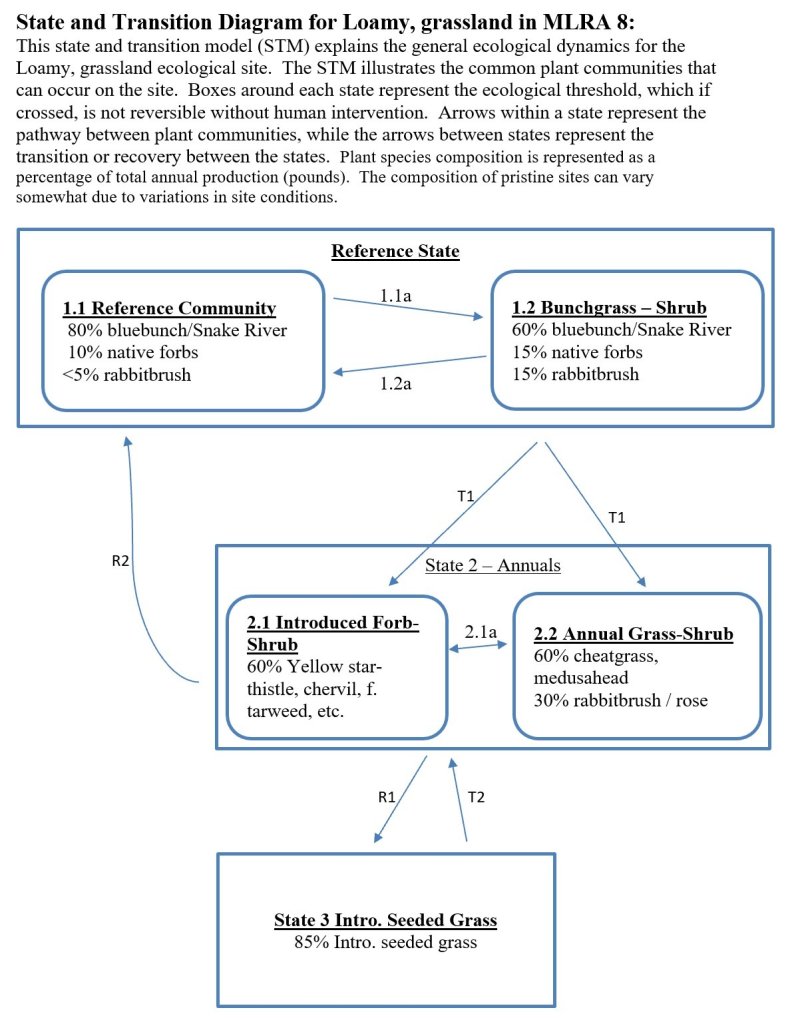

Vegetation dynamics

Ecological Dynamics:

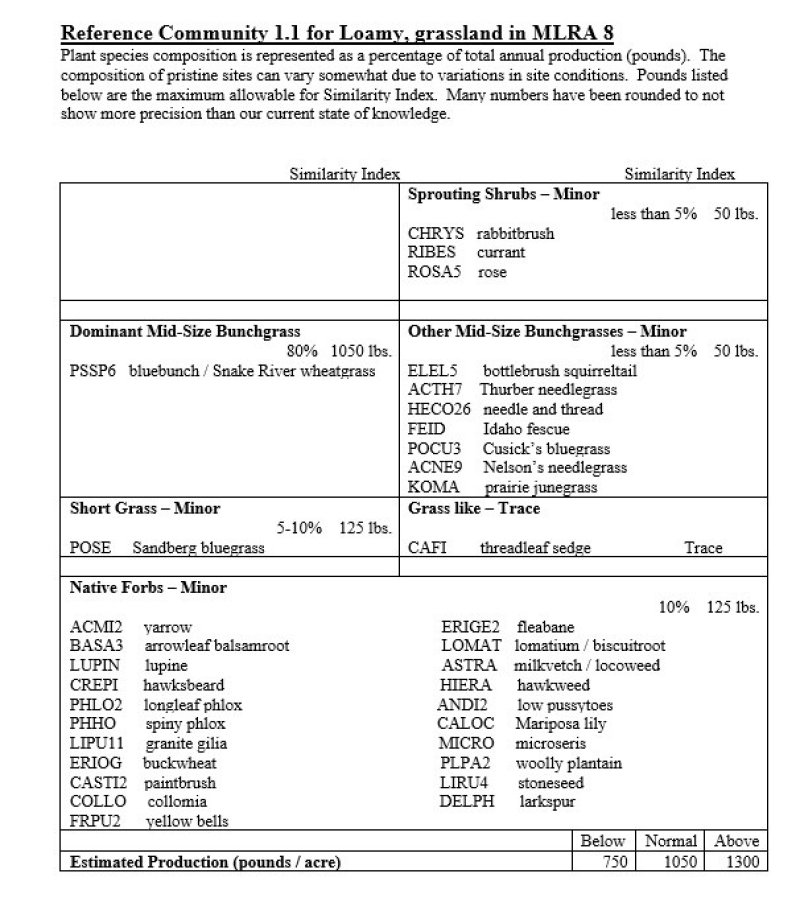

Loamy, grassland produces about 750-1300 pounds/acre of biomass annually.

The line between sagebrush steppe and true grasslands has been discussed and debated for many years. Daubenmire states that the line has nothing to do with pre-settlement as native ungulates played no significant role in the evolution of ecotypes. He also says that there is no evidence that the distribution of vegetative types is related to fire. And he also says there is no useful correlation between soil classification and the line between grasslands and sagebrush steppe.

The ecotones between Daubenmire’s vegetation types can be defined on the basis of consistent differences in climate and consistent differences in vegetation. Higher spring precipitation, especially in March, favors grasses over sagebrush. The grassland area of southeastern Adams and eastern Franklin counties have more precipitation in March. The same for the grasslands in Walla Walla, Asotin and Garfield counties. The Goldendale Prairie and the high elevation grassland above Coulee Dam in Douglas county also have higher spring precipitation. So, the grassland areas of MLRA 8 are consistent with Daubenmire’s findings.

Bluebunch wheatgrass is a long-lived, mid-sized bunchgrass with an awned or awnless spike seed head. Bluebunch provides a crucial and extensive network of roots to the upper portions (up to 48” deep in soils with no root-restrictive horizons) of the soil profile. These roots create a massive underground source to stabilize the soils, provide organic matter and nutrients inputs, and help maintain soil pore space for water infiltration and water retention in the soil profile. The extensive rooting system of mid-sized bunchgrasses leave very little soil niche space available for invasion by other species. This drought resistant root can compete, with and, suppress the spread of exotic weeds.

The stability and resiliency of the reference communities is directly linked to the health and vigor of bluebunch wheatgrass. Refer to page 8 for more details about bluebunch physiology. Research has found that the community remains resistant to medusahead if the site maintains at least 0.8 mid-sized bunchgrass plant/sq. ft. (K. Davies, 2008). The relationship between bunchgrasses and other invasive species should be similar. It is bluebunch that holds the system together. If we lose the bluebunch the ecosystem crashes or unravels.

The natural climax condition consists of widely spaced bluebunch wheatgrass plants which allows vernal forbs to flourish, particularly in years of above-normal precipitation. Six weeks fescue and Sandberg bluegrass would have been typical early spring species. In the presence of introduced weeds and historic disturbance, native annual grasses have been replaced with a variety of invasive species which threaten the native grasslands even in absence of grazing use

The natural disturbance regime for grassland communities is periodic lightning-caused fires. The fire return intervals (FRI) listed in research for sagebrush steppe communities is quite variable. Ponderosa pine communities have the shortest FRI of about 10-20 years (Miller). The FRI increases as one moves to wetter forested sites or to dries shrub steppe

communities. Given the uncertainties and opinions of reviewers, a mean of 75 years was chosen for Wyoming sagebrush communities (Rapid Assessment Model). This would place the historic FRI for grassland steppe around 30-50 years

The effect of fire on the community depends upon the severity of the burn. With a light to moderate fire there can be a mosaic of burned and unburned patches. Bunchgrasses thrive as the fire does not get into the crown. With adequate soil moisture Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass can make tremendous growth the year after the fire. Largely, the community is not affected by lower intensity fire.

A severe fire puts stress on the entire community. Bluebunch wheatgrass and basin wildrye will have weak vigor for a few years but generally survive. Spots and areas that were completely sterilized are especially vulnerable to exotic invasive species. Sterilized spots must be seeded to prevent invasive species (annual grasses, tumble mustard) from totally occupying the site. Needle and thread is one native species that can increase via new seedlings.

Grazing is another common disturbance that occurs to this ecological site. Grazing pressure can be defined as heavy grazing intensity, or frequent grazing during reproductive growth, or season-long grazing (the same plants grazed more than once). As grazing pressure increases the plant community unravels in stages:

1. Cusick bluegrass, a highly desirable and palatable bunchgrass, declines and is eliminated. Adjacent native species fill the void.

2. Bluebunch wheatgrass declines while Sandberg bluegrass and needle and thread increase

3. As bluebunch continues to decline invasive species such as cheatgrass, chervil or Yellow star-thistle colonize the site

4. With further decline the site can become a community dominated by invasive species

Managing grasslands to improve the vigor and health of native bunchgrasses begins with an understanding of grass physiology. New growth each year begins from basal buds. Bluebunch wheatgrass plants rely principally on tillering, rather than establishment of new plants through natural reseeding. During seed formation, the growing points become elevated and are vulnerable to damage or removal.

If defoliated during the formation of seeds, bluebunch wheatgrass has limited capacity to tiller compared with other, more grazing resistant grasses (Caldwell et al., 1981). Repeated critical period grazing (boot stage through seed formation) is especially damaging. Over several years each native bunchgrass pasture should be rested during the critical period two out of every three years (approximately April 15–July 15). And each

pasture should be rested the entire growing-season every third year (approximately March 1 – July 15).

In the spring each year it is important to monitor and maintain an adequate top growth: (1) so plants have enough energy to replace basal buds annually, (2) to optimize regrowth following spring grazing, and (3) to protect the elevated growing points of bluebunch wheatgrass.

Bluebunch wheatgrass remains competitive if:

(1) Basal buds are replaced annually,

(2) Enough top-growth is maintained for growth and protection of growing points, and

(3) The timing of grazing and non-grazing is managed over a several-year period. Careful management of late spring grazing is especially critical

For more grazing management information refer to Range Technical Notes found in Section I Reference Lists of NRCS Field Office Technical Guide for Washington State.

In Washington, bluebunch wheatgrass communities provide habitat for many upland wildlife species.

Supporting Information:

Associated Sites:

Loamy, grassland is associated with other ecological sites in the MLRA 8 grassland areas of Douglas County, Asotin County and counties nearby Asotin. Associated sites include North Aspect grassland, Very Shallow and Riparian Complex

Similar Sites:

Loamy, grassland is a bluebunch / Snake River wheatgrass ecological site. Sagebrush is not present while Idaho fescue is minor. In MLRA 8 other Loamy sites have sagebrush or much higher amounts of Idaho fescue.

Inventory Data References (narrative):

Data to populate Reference Community came from several sources: (1) NRCS ecological sites from 2004, (2) Soil Conservation Service range sites from 1980s and 1990s, (3) Daubenmire’s habitat types, and (4) ecological systems from Natural Heritage Program

Major Land Resource Area

MLRA 008X

Columbia Plateau

Subclasses

Stage

Provisional

Contributors

Provisional Site Author: Kevin Guinn

Technical Team: K. Moseley, G. Fults, R. Fleenor, W. Keller, C. Smith, K. Bomberger, C. Gaines, K. Paup-Lefferts

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.