Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R024XY014NV

COARSE SILTY 4-8 P.Z.

Last updated: 3/07/2025

Accessed: 02/27/2026

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 024X–Humboldt Basin and Range Area

Major land resource area (MLRA) 24, the Humboldt Area, covers an area of approximately 8,115,200 acres (12,680 sq. mi.). It is found in the Great Basin Section of the Basin and Range Province of the Intermontane Plateaus. Elevations range from 3,950 to 5,900 feet (1,205 to 1,800 meters) in most of the area, some mountain peaks are more than 8,850 feet (2,700 meters).

A series of widely spaced north-south trending mountain ranges are separated by broad valleys filled with alluvium washed in from adjacent mountain ranges. Most valleys are drained by tributaries to the Humboldt River. However, playas occur in lower elevation valleys with closed drainage systems. Isolated ranges are dissected, uplifted fault-block mountains. Geology is comprised of Mesozoic and Paleozoic volcanic rock and marine and continental sediments. Occasional young andesite and basalt flows (6 to 17 million years old) occur at the margins of the mountains. Dominant soil orders include Aridisols, Entisols, Inceptisols and Mollisols. Soils of the area are generally characterized by a mesic soil temperature regime, an aridic soil moisture regime and mixed geology. They are generally well drained, loamy and very deep.

Approximately 75 percent of MLRA 24 is federally owned, the remainder is primarily used for farming, ranching and mining. Irrigated land makes up about 3 percent of the area; the majority of irrigation water is from surface water sources, such as the Humboldt River and Rye Patch Reservoir. Annual precipitation ranges from 6 to 12 inches (15 to 30 cm) for most of the area, but can be as much as 40 inches (101 cm) in the mountain ranges. The majority of annual precipitation occurs as snow in the winter. Rainfall occurs as high-intensity, convective thunderstorms in the spring and fall.

Ecological site concept

This ecological site is on fan piedmonts. Soils associated with this site are very deep, well drained and formed in alluvium derived from mixed rocks, loess and volcanic ash. The soil profile is characterized by an ochric epipedon, a sodium free surface, and moderately to strongly sodium effected subsoil. Soil textures are dominated by silt loam, ashy very fine silt loam, and/or ashy fine sandy loam. The soil temperature regime is mesic, and the soil moisture regime is typic aridic.

The reference state is dominated by Winterfat, Bud sagebrush and Indian ricegrass.

Future field work in compare the soil characteristics and abiotic factors for all Winterfat dominated ESCs (024XY004NV, 024XY011NV, 024XY014NV, 024XY059NV & 024XY011OR) in MRLA 24 and determine if they are actually one ESC.

Associated sites

| R024XY004NV |

SILTY 4-8 P.Z. Soils associated with this site are very deep, well drained and formed in alluvium derived from mixed rocks, loess and volcanic ash. The soil profile is characterized by an ochric epipedon, a sodium free surface, and moderately to strongly sodium effected subsoil. Soil textures are dominated by silt loam, ashy very fine silt loam, and/or ashy fine sandy loam. The soil temperature regime is mesic and the soil moisture regime is typic aridic. |

|---|---|

| R024XY020NV |

DROUGHTY LOAM 8-10 P.Z. Important abiotic factors contributing to the presence of this site include limited available soil moisture due to texture and precipitation zone. Vegetative cover is less than 25 percent and is dominated by deep-rooted, cool season perennial bunchgrasses and drought tolerant shrubs. Dominant species include Thurber’s needlegrass (ACTH7), Indian ricegrass (ACHY), Wyoming big sagebrush (ARTRW8), and spiny hopsage (GRSP). |

| R024XY030NV |

SHALLOW CALCAREOUS LOAM 8-10 P.Z. Important abiotic factors contributing to the presence of this site include shallow depth, low available water holding capacity and less than 10 percent CaCO3 in the surface and subsurface. The soil profile is characterized by an ochric epipedon, effervescence throughout the profile and less than 35 percent rock fragments by volume. |

Similar sites

| R024XY004NV |

SILTY 4-8 P.Z. More productive site; greater shrub diversity. Winterfat (KRLA2) |

|---|---|

| R024XY059NV |

SILTY 8-10 P.Z. May be same plant community as this site. Winterfat (KRLA2) and Indian ricegrass (ACHY). |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Krascheninnikovia lanata |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Achnatherum hymenoides |

Physiographic features

This site is on middle and lower fan piedmonts, alluvial flats and alluvial plains. Slopes range from 0 to 30 percent, but slope gradients of 0 to 4 percent are most typical. Elevations are 3800 to 6000 feet (1158 to1829m.)

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Alluvial fan

(2) Fan skirt |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Low to medium |

| Flooding duration | Very brief (4 to 48 hours) |

| Flooding frequency | Rare to frequent |

| Elevation | 3,800 – 6,000 ft |

| Slope | 30% |

| Water table depth | 72 in |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate associated with this site is semiarid and characterized by cool, moist winters and warm, dry summers. Average annual precipitation is 4 to 8 inches (10 to 20cm.) Mean annual air temperature is 45 to 53 degrees F. The average growing season is about 90 to 130 days.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 130 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | |

| Precipitation total (average) | 8 in |

Figure 1. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Influencing water features

There are no influencing water features associated with this site.

Soil features

The soils associated with this site are very deep, well drained and formed in alluvium derived from mixed rocks, loess, and volcanic ash. The soil profile is characterized by an ochric epipedon, a cambic horizon, and silt loam textures throughout. The soil profile is moderately to strongly alkaline at depth, but its not salt affected at the surface.

Permeability is moderate to slow and available water capacity is high. The soil temperature regime is mesic and the soil moisture regime is typic aridic.

Soil series associated with this site include: Broyles, Creemon, Jerval, Trocken, and Wholan.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Alluvium

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Gravelly sandy loam (2) Gravelly fine sandy loam (3) Very fine sandy loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Loamy |

| Drainage class | Well drained |

| Permeability class | Moderate |

| Soil depth | 72 – 84 in |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 24% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 3% |

| Available water capacity (0-40in) |

2 – 7.9 in |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-40in) |

15% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-40in) |

32 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-40in) |

30 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-40in) |

6.6 – 9.6 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

48% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

5% |

Ecological dynamics

An ecological site is the product of all the environmental factors responsible for its development and it has a set of key characteristics that influence a site’s resilience to disturbance and resistance to invasives. Key characteristics include 1) climate (precipitation, temperature), 2) topography (aspect, slope, elevation, and landform), 3) hydrology (infiltration, runoff), 4) soils (depth, texture, structure, organic matter), 5) plant communities (functional groups, productivity), and 6) natural disturbance regime (fire, herbivory, etc.) (Caudle 2013). Biotic factors that influence resilience include site productivity, species composition and structure, and population regulation and regeneration (Chambers et al. 2013).

Winterfat is a long-lived, drought tolerant, native shrub typically about 30 cm tall (Mozingo 1987). It has a woody base from which annual branchlets grow (Welsh et al. 1987). The most common variety is a low growing dwarf form (less than 38.1 cm), which is most often found on desert valley floors (Stevens et al. 1977). Total winter precipitation is a primary growth driver and lower than average spring precipitation can reverse the impact of plentiful winter precipitation. While summer rainfall has a limited impact, heavy August-September rain can cause a second flowering in winterfat (West and Gasto 1978). Winterfat reproduces from seed and primarily pollinates via wind (Stevens et al. 1977). Seed production, especially in desert regions, is dependent on precipitation (West and Gasto 1978) with good seed years occurring when there is appreciable summer precipitation and little browsing (Stevens et al. 1977).Winterfat has multiple dispersal mechanisms: diaspores are shed in the fall or winter, dispersed by wind, rodent-cached, or carried on animals (Majerus 2003). Diaspores take advantage of available moisture, tolerating freezing conditions as they progress from imbibed seeds to germinants to nonwoody seedlings (Booth 1989). Under some circumstances, the degree of reproduction may be dependent on mature plant density (Freeman and Emlen 1995).

These communities often exhibit the formation of microbiotic crusts within the interspaces between shrubs. These crusts influence the soils on these sites and their ability to reduce erosion and increase infiltration; they may also alter the soil structure and possibly increase soil fertility (Fletcher and Martin 1948, Williams 1993). Finer textured soils such as silts tend to support more microbiotic cover than coarse texture soils (Anderson 1982). Disturbance such as hoof action from inappropriate grazing and cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) invasion can reduce biotic crust integrity (Anderson 1982, Ponzetti et al. 2007) and increase erosion.

Drought and/or inappropriate grazing will initially favor shrubs but prolonged drought can cause a decrease in the winterfat, bud sagebrush and other shrubs, while bare ground increases. Indian ricegrass will decrease with inappropriate grazing management. Squirreltail may maintain or also decline within the community. Repeated spring and early summer grazing will have an especially detrimental effect on winterfat and bud sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata). Cheatgrass and other non-native annual weeds increase with excessive grazing. Abusive grazing during the winter may lead to soil compaction and reduced infiltration. Prolonged abusive grazing during any season leads to abundant bare ground, desert pavement and active wind and water erosion. Repeated, frequent fire will promote cheatgrass dominance and elimination of the native plant community. These sites frequently attract recreational use, primarily by off highway vehicles (OHV). Annual non-native species increase where surface soils have been disturbed. Three alternative stable states have been identified for this site.

Fire Ecology:

Winterfat tolerates environmental stress, extremes of temperature and precipitation, and competition from other perennials but not the disturbance of fire or overgrazing (Ogle 2001). Fire is rare within these communities due to low fuel loads. There are conflicting reports in the literature about the response of winterfat to fire. In one of the first published descriptions, Dwyer and Pieper (1967) reported that winterfat sprouts vigorously after fire. This observation was frequently cited in subsequent literature, but recent observations have suggested that winterfat can be completely killed by fire (Pellant and Reichert 1984). The response is apparently dependent on fire severity. Winterfat is able to sprout from buds near the base of the plant. However, if these buds are destroyed, winterfat will not sprout. Research has shown that winterfat seedling growth is depressed in growth by at least 90% when growing in the presence of cheatgrass (Hild et al. 2007). Repeated, frequent fires will increase the likelihood of conversion to a non-native, annual plant community with trace amounts of winterfat.

Bud sagebrush (Picrothamnus desertorum), a minor shrub to this ecological site, is a native, summer-deciduous shrub. It is low growing, spinescent, aromatic shrub with a height of 4 to 10 inches and a spread of 8 to 12 inches (Chambers and Norton 1993). Bud sagebrush is fire intolerant and must reestablish from seed (Banner 1992, West 1994).

Indian ricegrass, the dominant grass within this site, is a hardy, cool-season, densely tufted, native perennial bunchgrass that grows from 4 to 24 inches in height (Blaisdell and Holmgren 1984). Indian ricegrass has been found to reestablish on burned sites through seed dispersed from adjacent unburned areas (Young 1983). Thus the presence of surviving, seed producing plants is necessary for reestablishment of Indian ricegrass. Grazing management following fire to promote seed production and establishment of seedlings is important.

Bottlebrush squirreltail, another cool-season, native perennial bunchgrass is common to this ecological site. Bottlebrush squirreltail is considered more fire tolerant than Indian ricegrass due to its small size, coarse stems, and sparse leafy material (Britton et al. 1990). Postfire regeneration occurs from surviving root crowns and from on- and off-site seed sources. Bottlebrush squirreltail has the ability to produce large numbers of highly germinable seeds, with relatively rapid germination (Young and Evans 1977) when exposed to the correct environmental cues. Early spring growth and ability to grow at low temperatures contribute to the persistence of bottlebrush squirreltail among cheatgrass dominated ranges (Hironaka and Tisdale 1972).

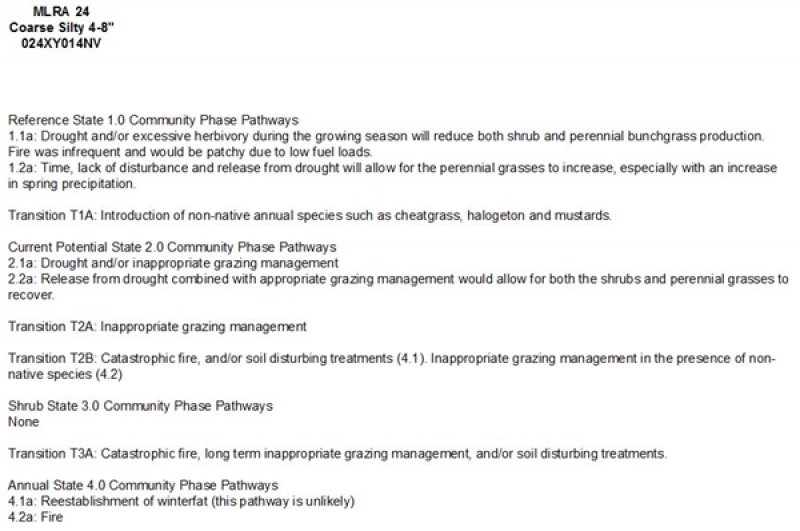

State and transition model

Figure 2. T. Stringham 4/2016

Figure 3. Legend

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference State

Community 1.1

Reference Plant Community

The reference plant community is dominated by winterfat and bud sagebrush. Shadscale, Indian ricegrass and bottlebrush squirreltail are important species associated with this site. Potential vegetative composition is about 45% grasses, 5% forbs and 50% shrubs. Approximate ground cover (basal and crown) is 10 to 20 percent.

Figure 4. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (lb/acre) |

Representative value (lb/acre) |

High (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrub/Vine | 100 | 250 | 350 |

| Grass/Grasslike | 90 | 225 | 315 |

| Forb | 10 | 25 | 35 |

| Total | 200 | 500 | 700 |

Community 1.2

Plant community 1.2

Drought will favor shrubs over perennial bunchgrasses. However, long-term drought will result in an overall decline in the plant community, regardless of functional group.

Pathway a

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Long term drought and/or herbivory. Fires would also decrease vegetation on these sites but would be infrequent and patchy due to low fuel loads.

Pathway a

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Time, lack of disturbance and recovery from drought would allow the vegetation to increase and bare ground would eventually decrease.

State 2

Current Potential State

This state is similar to the Reference State 1.0. This state has the same two general community phases. Ecological function has not changed, however the resiliency of the state has been reduced by the presence of invasive weeds. Non-natives may increase in abundance but will not become dominant within this State. These non-natives can be highly flammable and can promote fire where historically fire had been infrequent. Negative feedbacks enhance ecosystem resilience and contribute to the stability of the state. These feedbacks include the presence of all structural and functional groups, low fine fuel loads, and retention of organic matter and nutrients. Positive feedbacks decrease ecosystem resilience and stability of the state. These include the non-natives’ high seed output, persistent seed bank, rapid growth rate, ability to cross pollinate, and adaptations for seed dispersal.

Community 2.1

Plant community 2.1

This community is dominated by winterfat and Indian ricegrass. Bottlebrush squirreltail and bud sagebrush are also important species on this site. Community phase changes are primarily a function of chronic drought. Fire is infrequent and patchy due to low fuel loads. Non-native annual species are present.

Community 2.2

Plant community 2.2

This community is dominated by winterfat. The perennial grass component is significantly reduced.

Pathway a

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Drought will favor shrubs over perennial bunchgrasses. However, long-term drought will result in an overall decline in the plant community, regardless of functional group. Inappropriate grazing management will favor unpalatable shrubs such as shadscale, and cause a decline in winterfat and budsage.

Pathway a

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Release from long term drought and/or growing season grazing pressure allows recovery of bunchgrasses, winterfat, and bud sagebrush.

State 3

Shrub State

This state consists of one community phase. This site has crossed a biotic threshold and site processes are being controlled by shrubs. Bare ground has increased.

Community 3.1

Plant community 3.1

Perennial bunchgrasses, like Indian ricegrass are reduced and the site is dominated by winterfat. Rabbitbrush and shadscale may be significant components or dominant shrubs. Annual non-native species increase. Bare ground has increased.

State 4

Annual State

This state consists of two community phases. This state is characterized by the dominance of annual non-native species such as halogeton and cheatgrass. Rabbitbrush, shadscale, sickle saltbush and other sprouting shrubs may dominate the overstory.

Community 4.1

Plant community 4.1

Figure 5. T. Stringham, August 2010, NV775, MU 231 Broyles s

This community is dominated by annual non-native species. Trace amounts of winterfat and other shrubs may be present, but are not contributing to site function. Bare ground may be abundant, especially during low precipitation years. Soil erosion, soil temperature and wind are driving factors in site function.

Community 4.2

Plant community 4.2

This community is dominated by winterfat with an understory of non-native annual species. Perennial bunchgrasses may be a minor component or missing. Bare ground may be abundant.

Pathway a

Community 4.1 to 4.2

Reestablishment of winterfat. This pathway is unlikely due to the impact of annual non-native species on the establishment and growth of winterfat seedlings.

Pathway a

Community 4.2 to 4.1

wildfire

Transition 1A

State 1 to 2

Trigger: This transition is caused by the introduction of non-native annual plants, such as halogeton and cheatgrass. Slow variables: Over time the annual non-native species will increase within the community. Threshold: Any amount of introduced non-native species causes an immediate decrease in the resilience of the site. Annual non-native species cannot be easily removed from the system and have the potential to significantly alter disturbance regimes from their historic range of variation.

Transition 2A

State 2 to 3

Trigger: Inappropriate, long-term grazing of perennial bunchgrasses during the growing season and/or long term drought will favor shrubs and initiate a transition to Community phase 3.1. Slow variables: Long term decrease in deep-rooted perennial grass density. Threshold: Loss of deep-rooted perennial bunchgrasses changes nutrient cycling, nutrient redistribution, and reduces soil organic matter.

Transition 2B

State 2 to 4

Trigger: Severe fire/ multiple fires and/or soil disturbing treatments would transition to Community Phase 4.1. Long term inappropriate grazing management in the presence of non-native annual species would transition to Community Phase 4.2. Slow variables: Increased production and cover of non-native annual species. Threshold: Loss of deep-rooted perennial bunchgrasses and shrubs truncates, spatially and temporally, nutrient capture and cycling within the community. Increased, continuous fine fuels from annual non-native plants modify the fire regime by changing intensity, size and spatial variability of fires.

Transition 3A

State 3 to 4

Trigger: Severe fire/ multiple fires, long term inappropriate grazing management, and/or soil disturbing treatments such as plowing. Slow variables: Increased production and cover of non-native annual species. Threshold: Increased, continuous fine fuels modify the fire regime by changing intensity, size and spatial variability of fires. Changes in plant community composition and spatial variability of vegetation due to the loss of perennial bunchgrasses and sagebrush truncate energy capture spatially and temporally thus impacting nutrient cycling and distribution.

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (lb/acre) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Primary Perennial Grasses | 135–240 | ||||

| Indian ricegrass | ACHY | Achnatherum hymenoides | 125–200 | – | ||

| squirreltail | ELEL5 | Elymus elymoides | 10–40 | – | ||

| 2 | Secondary Perennial Grasses | 10–40 | ||||

| needle and thread | HECO26 | Hesperostipa comata | 3–15 | – | ||

| Sandberg bluegrass | POSE | Poa secunda | 3–15 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | Perennial Forbs | 10–40 | ||||

| evening primrose | OENOT | Oenothera | 3–10 | – | ||

| globemallow | SPHAE | Sphaeralcea | 3–10 | – | ||

| 4 | Annual Forbs | 1–20 | ||||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 5 | Primary Shrubs | 235–390 | ||||

| winterfat | KRLA2 | Krascheninnikovia lanata | 150–200 | – | ||

| shadscale saltbush | ATCO | Atriplex confertifolia | 10–40 | – | ||

| 6 | Secondary Shrubs | 10–40 | ||||

| yellow rabbitbrush | CHVI8 | Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus | 5–15 | – | ||

| spiny hopsage | GRSP | Grayia spinosa | 5–15 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

Livestock Interpretations:

Winterfat is a valuable forage species with an average of 10% crude protein during winter when there are few nutritious options for livestock and wildlife (Welch 1989). However, excessive grazing throughout the west has negatively impacted survival of winterfat stands (Hilton 1941; Statler 1967; Stevens et al. 1977). Time of grazing is critical for winterfat with the active growing period being most critical (Romo 1995). Stevens et al. (1977) found that both vigor and reproduction of winterfat were reduced in Steptoe Valley, Nevada by improper season of use, and he recommended no more than 25% utilization during periods of active growth and up to 75% utilization during dormant season use. Rasmussen and Brotherson (1986) found significantly greater foliar cover and density of winterfat in areas ungrazed for 26 years versus winter grazed areas in Utah. In exclosures protected from grazing for between 5 and 16 years, Rice and Westoby (1978) found that winterfat increased in foliar cover but not in density where it was dominant, and in both foliar cover and density in shadscale-perennial grass communities where it was not dominant.

In addition to grazing by cattle, winterfat is browsed by rabbits, antelope, and other wildlife species (Stevens et al. 1977, Ogle et al. 2001). Winterfat and perennial grasses average 80% of jackrabbits’ diet in southeastern Idaho, with shrubs being grazed in fall and winter particularly (Johnson and Anderson 1984). Pronghorn and rabbits browse stems, leaves, and seed stalks of winterfat year round, especially during periods of active growth (Stevens et al. 1977). Management of wildlife browse is difficult and browse may be harmful to winterfat reestablishment as seed production and regrowth are curtailed if grazing occurs as the plant begins to grow (Eckert 1954).

Heavy spring grazing has been found to sharply reduce the vigor of Indian ricegrass and decrease the stand (Cook and Child 1971). In eastern Idaho, productivity of Indian ricegrass was at least 10 times greater in undisturbed plots than in heavily grazed ones (Pearson 1976). Cook and Child (1971) found significant reduction in plant cover after 7 years of rest from heavy (90%) and moderate (60%) spring use. The seed crop may be reduced where grazing is heavy (Bich et al. 1995). Tolerance to grazing increases after May thus spring deferment may be necessary for stand enhancement (Pearson 1964, Cook and Child 1971); however, utilization of less than 60% is recommended.

Bottlebrush squirreltail generally increases in abundance when moderately grazed or protected (Hutchings and Stewart 1953). In addition, moderate trampling by livestock in big sagebrush rangelands of central Nevada enhanced bottlebrush squirreltail seedling emergence compared to untrampled conditions. Heavy trampling however was found to significantly reduce germination sites (Eckert et al. 1987). Squirreltail is more tolerant of grazing than Indian ricegrass but all bunchgrasses are sensitive to over utilization within the growing season.

Bud sagebrush is also a palatable, nutritious forage for upland game birds, small game, big game and domestic sheep in winter, particularly late winter (Johnson 1978), however it can be poisonous or fatal to calves when eaten in quantity (Stubbendieck et al. 1992). Budsage is highly susceptible to effects of browsing. It decreases under browsing due to year-long palatability of its buds and is particularly susceptible to browsing in the spring when it is physiologically most active (Chambers and Norton 1993). Heavy browsing (>50%) may kill budsage rapidly (Wood and Brotherson 1986).

Shadscale is a valuable browse species, providing a source of palatable, nutritious forage for a wide variety of livestock. Shadscale provides good browse for domestic sheep. Shadscale leaves and seeds are an important component of domestic sheep and cattle winter diets. Indian ricegrass is highly palatable to all classes of livestock in both green and cured condition. It supplies a source of green feed before most other native grasses have produced much new growth. Bottlebrush squirreltail is very palatable winter forage for domestic sheep of Intermountain ranges. Domestic sheep relish the green foliage. Overall, bottlebrush squirreltail is considered moderately palatable to livestock.

Stocking rates vary over time depending upon season of use, climate variations, site, and previous and current management goals. A safe starting stocking rate is an estimated stocking rate that is fine tuned by the client by adaptive management through the year and from year to year.

Wildlife Interpretations:

Winterfat is an important forage plant for wildlife, especially during winter when forage is scarce. Winterfat seeds are eaten by rodents and are a staple food for black-tailed jackrabbits. Mule deer and pronghorn antelope browse winterfat. Winterfat is used for cover by rodents. It is potential nesting cover for upland game birds, especially when grasses grow up through its crown. Budsage is palatable, nutritious forage for upland game birds, small game and big game in winter. Budsage is browsed by mule deer in Nevada in winter and is utilized by bighorn sheep in summer, but the importance of budsage in the diet of bighorns is not known. Bud sage comprises 18 – 35% of a pronghorn’s diet during the spring where it is available. Chukar will utilize the leaves and seeds of bud sage. Budsage is highly susceptible to effects of browsing. It decreases under browsing due to year-long palatability of its buds and is particularly susceptible to browsing in the spring when it is physiologically most active. Shadscale is a valuable browse species, providing a source of palatable, nutritious forage for a wide variety of wildlife particularly during spring and summer before the hardening of spiny twigs. It supplies browse, seed, and cover for birds, small mammals, rabbits, deer, and pronghorn antelope. Indian ricegrass is eaten by pronghorn in moderate amounts whenever available. A number of heteromyid rodents inhabiting desert rangelands show preference for seed of Indian ricegrass. Indian ricegrass is an important component of jackrabbit diets in spring and summer. In Nevada, Indian ricegrass may even dominate jackrabbit diets during the spring through early summer months. Indian ricegrass seed provides food for many species of birds. Doves, for example, eat large amounts of shattered Indian ricegrass seed lying on the ground. Bottlebrush squirreltail is a dietary component of several wildlife species. Bottlebrush squirreltail may provide forage for mule deer and pronghorn.

Hydrological functions

Runoff is low to medium. Permeability is moderate. Hydrologic soil group is B. Rills are none. Water flow patterns are rare to common depending on site location relative to major inflow areas. Pedestals are none. Gullies are none. Shrubs and deep-rooted perennial herbaceous bunchgrasses aid in infiltration. Shrub canopy and associated litter break raindrop impact and provide opportunity for snow catch and accumulation on site.

Recreational uses

Aesthetic value is derived from the diverse floral and faunal composition and the colorful flowering of wild flowers and shrubs during the spring and early summer. This site offers rewarding opportunities to photographers and for nature study. This site has potential for upland bird and big game hunting.

Other products

Seeds of shadscale were used by Native Americans for bread and mush. Indian ricegrass was traditionally eaten by some Native Americans. The Paiutes used seed as a reserve food source.

Other information

Winterfat adapts well to most site conditions, and its extensive root system stabilizes soil. However, winterfat is intolerant of flooding, excess water, and acidic soils. Bottlebrush squirreltail is tolerant of disturbance and is a suitable species for revegetation.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

NASIS soil component data.

Other references

Anderson, D. C., K. T. Harper, and S. R. Rushforth. 1982. Recovery of cryptogamic soil crusts from grazing on Utah winter ranges. Journal of Range Management 35:355-359.

Banner, R.E. 1992. Vegetation types of Utah. Journal of Range Management 14(2):109-114.

Bich, B.S., J.L. Butler, and C.A. Schmidt. 1995. Effects of differential livestock use of key plant species and rodent populations within selected Oryzopsis hymenoides/Hilaria jamesii communities in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. The Southwestern Naturalist 40(3):281-287.

Blaisdell, J.P. and R.C. Holmgren. 1984. Managing Intermountain rangelands – Salt-desert shrub ranges. USDA-FS General Technical Report INT-163. 52 p.

Booth, D.T. 1989. A model of freeze tolerance in winterfat germinants. In: Proceedings--Symposium on shrub ecophysiology and biotechnology; 1987 June 30-July 2; Logan, UT. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-256. Ogden, UT. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: Pgs 83-89.

Britton, C.M., G.R. McPherson, and F.A. Sneva. 1990. Effects of burning and clipping on five bunchgrasses in eastern Oregon. The Great Basin Naturalist 50(2):115-120.

Caudle, D., J. DiBenedetto, M. Karl, H. Sanchez, and C. Talbot. 2013. Interagency ecological site handbook for rangelands. Available at: http://jornada.nmsu.edu/sites/jornada.nmsu.edu/files/InteragencyEcolSiteHandbook.pdf. Accessed 4 October 2013.

Chambers, J.C. and B.E. Norton. 1993. Effects of grazing and drought on population dynamics of salt desert species on the Desert Experimental Range, Utah. Journal of Arid Environments 24:261-275.

Clark, L.D. and N.E. West. 1971. Further studies of Eurotia lanata germination in relation to salinity. The Southwestern Naturalist 15(3):371-375.

Cook, C.W. and R.D. Child. 1971. Recovery of desert plants in various states of vigor. Journal of Range Management 24(5):339-343.

Dwyer, D.D. and R.D. Pieper. 1967. Fire effects on blue grama--pinyon-juniper rangeland in New Mexico. Journal of Range Management 20:359-362.

Eckert, R.E., Jr. 1954. A study of competition between whitesage and halogeton in Nevada. Journal of Range Management 7:223-225.

Eckert, R.E., Jr., F.F. Peterson, and F.L. Emmerich. 1987. A study of factors influencing secondary succession in the sagebrush [Artemisia spp. L.] type. In: Frasier, G.W. and R.A. Evans, (eds.). Proceedings of the symposium: "Seed and seedbed ecology of rangeland plants"; 1987 April 21-23; Tucson, AZ. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service: Pgs 149-168.

Fletcher, J. E. and W. P. Martin. 1948. Some Effects of Algae and Molds in the Rain-Crust of Desert Soils. Ecology 29:95-100.

Freemen, D.C. and J.M. Emlen. 1995. Assessment of interspecific interactions in plant communities: an illustration from the cold desert saltbush grasslands of North America. Journal of Arid Environments 31:179-198.

Hild, A.L, J.M. Muscha, and N.L.Shaw. 2007. Emergence and growth of four winterfat accessions in the presence of the exotic annual cheatgrass. In: Sosebee, R.E., D.B. Wester, C.M. Britton, E.D. McArthur, and S.G. Kitchen (compilers). Proceedings: Shrubland dynamics—fire and water; 2004 Aug 10-12; Lubbock, TX. RMRS-P-47. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Pgs 147-152.

Hilton, J.W. 1941. Effects of certain micro-ecological factors on the germinability and early development of Eurotia lanata. Northwest Science 15:86-92.

Hironaka, M. and E.W. Tisdale. 1972. Growth and development of Sitanion hystrix and Poa sandbergii. Research Memorandum RM 72-24. U.S. International Biological Program, Desert Biome. 15 p.

Hutchings, S.S. and G. Stewart. 1953. Increasing forage yields and sheep production on Intermountain winter ranges. Circular No. 925. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture. 63 p.

Johnson, K.L. 1978. Wyoming shrublands: Proceedings, 7th Wyoming shrub ecology workshop; 1978 May 31-June 1; Rock Springs, WY. Laramie, WY: University of Wyoming, Agricultural Extension Service. 58 p.

Johnson, R.D. and J.E. Anderson. 1984. Diets of black-tailed jackrabbits in relation to population density and vegetation. Journal of Range Management 37:79-83.

Majerus, M. 2003. Production and conditioning of winterfat seeds (Krascheninnikovia lanata). Native Plants Journal 4(1):10-17.

Mozingo, H.N. 1987. Shrubs of the Great Basin: a natural history. University of Nevada Press, Reno, NV. 342 p.

Ogle, D.G., L. St. John, and L. Holzworth. 2001. Plant guide management and use of winterfat. Boise (ID): USDA-NRCS. 4 p.

Pearson, L.C. 1964. Effect of harvest date on recovery of range grasses and shrubs. Agronomy Journal 56:80-82.

Pearson, L.C. 1976. Primary production in grazed and ungrazed desert communities of eastern Idaho. Ecology 46(3):278-285.

Pellant, M. and L. Reichert. 1984. Management and rehabilitation of a burned winterfat community in southwestern Idaho. In: Tiedemann, Arthur R.; McArthur, E. Durant; Stutz, Howard C.; [and others], compilers. Proceedings--symposium on the biology of Atriplex and related chenopods; 1983 May 2-6; Provo, UT. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-172. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Pgs 281-285.

Ponzetti, J. M., B. McCune, and D. A. Pyke. 2007. Biotic Soil Crusts in Relation to Topography, Cheatgrass and Fire in the Columbia Basin, Washington. The Bryologist 110:706-722.

Rasmussen, L.L. and J.D. Brotherson. 1986. Response of winterfat communities to release from grazing pressure. Great Basin Naturalist 46:148-156.

Rice, B. and M. Westoby. 1978. Vegetative responses of some Great Basin shrub-communities protected against jackrabbits or domestic stock. Journal of Range Management 31:28-34.

Romo, J.T., R.E. Redmann, B.L. Kowalenko, and A.R. Nicholson. 1995. Growth of winterfat following defoliation in northern mixed prairie of Saskatchewan. Journal of Range Management 48:240-245.

Statler, G.D. 1967. Eurotia lanata establishment trials. Journal of Range Management 20:253-255.

Stevens, R., B.C. Giunta, K.R. Jorgensen, and A.P. Plummer. Winterfat (Ceratoides lanata). Publ. No. 77-2. Salt Lake City, UT: Utah State Division of Wildlife Resources. 41 p.

Stubbendieck, J., S.L. Hatch, and C.H. Butterfield. 1992. North American range plants. 4th ed. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. 493 p.

Welch, B.L. 1989. Nutritive value of shrubs. In: McKell, C.M. (ed.). The biology and utilization of shrubs. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc. Pgs 405-424.

Welsh, S.L., N.D. Atwood, S. Goodrich, L.C. Higgins, (eds.). 1987. A Utah flora. The Great Basin Naturalist Memoir No. 9. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University. 894 p.

West, N.E. 1994. Effects of fire on salt-desert shrub rangelands. In: Monsen, S.B. and S.G. Kitchen (compilers). Proceedings--ecology and management of annual rangelands; 1992 May 18-22; Boise, ID. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-GTR-313. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: Pgs 71-74.

West, N.E. and J. Gasto. 1978. Phenology of the aerial portions of shadscale and winterfat in Curlew Valley, Utah. Journal of Range Management 31(1):43-45.

Wood, B.W. and J.D. Brotherson. 1986. Ecological adaptation and grazing response of budsage (Artemisia spinescens). In: McArthur, E.D. and B.L. Welch (compilers). Proceedings--symposium on the biology of Artemisia and Chrysothamnus; 1984 July 9-13; Provo, UT. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-200. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: 75-92.

Workman, J.P. and N.E. West. 1967. Germination of Eurotia lanata in relation to temperature and salinity. Ecology 48(4):659-661.

Williams, J. D. 1993. Influence of microphytic crusts on selected soil physical and hydrologic properties in the Hartnet Draw, Capital Reef National Park Utah. Utah State University.

Young, R.P. 1983. Fire as a vegetation management tool in rangelands of the Intermountain Region. In: Monsen, S.B. and N. Shaw (compilers). Managing Intermountain rangelands--improvement of range and wildlife habitats: Proceedings; 1981 September 15-17; Twin Falls, ID; 1982 June 22-24; Elko, NV. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-157. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Pgs 18-31.

Young, J.A. and R.A. Evans 1977. Squirreltail seed germination. Journal of Range Management 30(1):33-36.

Young, R.P. 1983. Fire as a vegetation management tool in rangelands of the Intermountain region. In: Monsen, S.B. and N. Shaw (Eds). Managing Intermountain rangelands—improvement of range and wildlife habitats: Proceedings of symposia; 1981 September 15-17; Twin Falls, ID; 1982 June 22-24; Elko, NV. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-157. Ogden, UT. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. Pp. 18-31.

Contributors

CP/GKB

T Stringham

P NovakEchenique

Approval

Kendra Moseley, 3/07/2025

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Patti Novak-Echenique |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | State Rangeland Management Specialist |

| Date | 02/05/2010 |

| Approved by | Kendra Moseley |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

Rills are not typical. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

Water flow patterns are rare to common depending on site location relative to major inflow areas. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

Pedestals are none. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

Bare Ground ± 60%. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

None -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Fine litter (foliage of grasses and annual & perennial forbs) expected to move distance of slope length during periods of intense summer convection storms or run in of early spring snow melt flows. Persistent litter (large woody material) will remain in place except during unusual flooding (ponding) events. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Soil stability values will range from 1 to 4. (To be field tested.) -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

Structure of soil surface is thin to medium platy or subangular blocky. Soil surface colors are very light and soils are typified by an ochric epipedon. Organic matter is typically 0.1-1.4 percent (OM values taken from lab characterization data). -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

Shrubs and deep-rooted perennial herbaceous bunchgrasses aid in infiltration. Shrub canopy and associated litter break raindrop impact and provide opportunity for snow catch and accumulation on site. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

Compacted layers are not typical. Platy, subangular blocky, prismatic, or massive subsurface layers are normal for this site and are not to be interpreted as compaction. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Low statured or half shrubs (winterfat & budsage) > deep-rooted, cool season, perennial bunchgrassesSub-dominant:

shallow-rooted cool season, perennial bunchgrasses > associated shrubs = deep-rooted, cool season, perennial forbs = fibrous, shallow-rooted, cool season, perennial and annual forbs.Other:

Microbiotic crustsAdditional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

Dead branches within individual shrubs common and standing dead shrub canopy material may be as much as 35% of total woody canopy. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Between plant interspaces (< 15%) and depth (± ¼ in.). -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

For normal or average growing season (March thru May) ± 500 lbs/ac. Favorable years ± 700 lbs/ac and unfavorable years ±200 lbs/ac. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Potential invaders include cheatgrass, annual mustards, annual kochia, Russian thistle, and halogeton. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

All functional groups should reproduce in average (or normal) and above average growing season years. Reduced growth and reproduction occur during extended and extreme drought years.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.