Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R024XY044NV

WET SODIC FLAT

Last updated: 3/06/2025

Accessed: 03/18/2025

General information

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 024X–Humboldt Basin and Range Area

Major land resource area (MLRA) 24, the Humboldt Area, covers an area of approximately 8,115,200 acres (12,680 sq. mi.). It is found in the Great Basin Section of the Basin and Range Province of the Intermontane Plateaus. Elevations range from 3,950 to 5,900 feet (1,205 to 1,800 meters) in most of the area, some mountain peaks are more than 8,850 feet (2,700 meters).

A series of widely spaced north-south trending mountain ranges are separated by broad valleys filled with alluvium washed in from adjacent mountain ranges. Most valleys are drained by tributaries to the Humboldt River. However, playas occur in lower elevation valleys with closed drainage systems. Isolated ranges are dissected, uplifted fault-block mountains. Geology is comprised of Mesozoic and Paleozoic volcanic rock and marine and continental sediments. Occasional young andesite and basalt flows (6 to 17 million years old) occur at the margins of the mountains. Dominant soil orders include Aridisols, Entisols, Inceptisols and Mollisols. Soils of the area are generally characterized by a mesic soil temperature regime, an aridic soil moisture regime and mixed geology. They are generally well drained, loamy and very deep.

Approximately 75 percent of MLRA 24 is federally owned, the remainder is primarily used for farming, ranching and mining. Irrigated land makes up about 3 percent of the area; the majority of irrigation water is from surface water sources, such as the Humboldt River and Rye Patch Reservoir. Annual precipitation ranges from 6 to 12 inches (15 to 30 cm) for most of the area, but can be as much as 40 inches (101 cm) in the mountain ranges. The majority of annual precipitation occurs as snow in the winter. Rainfall occurs as high-intensity, convective thunderstorms in the spring and fall.

Ecological site concept

This ecological site is on lake plains. Soils are very deep, somewhat poorly drained and formed in alluvium derived from mixed sources. The soil profile is saline-sodic with a pH of 9.0 at the surface, EC of 4 to 32 and SAR of 13 to 90.

Important abiotic factors contributing to the presence of this site include the strongly saline-sodic conditions in the soil profile and shallow depth to a water table.

Full consideration should be given to combining this ESC with 024XY010NV as a community phase.

Associated sites

| R024XY007NV |

SALINE BOTTOM The soil profile is characterized by an ochric epipedon, strong to moderate salinity throughout and a high-water table between 70-100cm at some time during the year. Sodicity (SAR) is 13-99 in the upper 50cm and decreases with depth. Dominant plant species are Black greasewood (SAVE4) and Basin wildrye (LECI4) |

|---|---|

| R024XY011NV |

SODIC FLAT 6-8 P.Z. Important abiotic factors include crusting & baking of the surface layer upon drying, inhibiting water infiltration and seedling emergence. High salt concentrations reduce seed viability, germination and the available water capacity of these soils. |

| R024XY043NV |

WET MEADOW 6-8 P.Z. This site is found near seeps and springs on basin floors, as well as flood plains and lava plains associated with perennial streams. Soils are very deep, very poorly drained and formed in alluvium derived from mixed rocks. |

Similar sites

| R024XY010NV |

SODIC FLOODPLAIN Iodinebush (ALOC2) dominant shrub. |

|---|---|

| R024XY011NV |

SODIC FLAT 6-8 P.Z. Greasewood (SAVE4) dominant shrub. |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

(1) Chrysothamnus albidus |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Distichlis spicata |

Physiographic features

This site is on basin floor lake plains, usually at the playa fringe. Slopes are less than 2 percent. Elevations are 5600 to about 5700 feet (1707 to about 1737m).

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Basin floor

(2) Lake plain (3) Playa rim |

|---|---|

| Runoff class | Medium to very high |

| Flooding duration | Brief (2 to 7 days) |

| Flooding frequency | Frequent |

| Elevation | 1,067 – 1,768 m |

| Slope | 0 – 2% |

| Water table depth | 69 – 213 cm |

| Aspect | Aspect is not a significant factor |

Climatic features

The climate associated with this site is semiarid and characterized by cool, moist winters and warm, dry summers. Average annual precipitation is 6 to 8 inches (15 to 20cm). Mean annual air temperature is 45 to 53 degrees F. The average growing season is about 90 to 130 days.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 130 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | |

| Precipitation total (average) | 203 mm |

Figure 1. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 2. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Influencing water features

There are no influencing water features associated with this site.

Soil features

The soils associated with this site are very deep, poorly drained and formed in alluvium derived from mixed sources. The soil profile is saline-sodic with a pH of 9.0 at the surface, EC of 4 to 32 and SAR of 13 to 90. A water table is found between 18 to 39 inches (46 to 100 cm) in the spring.

These soils are strongly salt and sodium affected with a very high concentration of salts at or near the surface due to capillary movement of dissolved salts upward from the ground water. High salt concentrations reduce the available water capacity of these soils and adversely affect seed viability and germination.

Skullwak soil component is correlated to the Wet Sodic Flat site.

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Parent material |

(1)

Alluvium

|

|---|---|

| Surface texture |

(1) Silt loam |

| Family particle size |

(1) Clayey |

| Drainage class | Poorly drained |

| Permeability class | Very slow |

| Soil depth | 183 – 213 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

20.07 – 20.32 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

1 – 15% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

8 – 32 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

13 – 45 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

7.9 – 9.6 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

0% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0% |

Ecological dynamics

An ecological site is the product of all the environmental factors responsible for its development and it has a set of key characteristics that influence a site’s resilience to disturbance and resistance to invasives. Key characteristics include 1) climate (precipitation, temperature), 2) topography (aspect, slope, elevation, and landform), 3) hydrology (infiltration, runoff), 4) soils (depth, texture, structure, organic matter), 5) plant communities (functional groups, productivity), and 6) natural disturbance regime (fire, herbivory, etc.) (Caudle et al 2013). Biotic factors that influence resilience include site productivity, species composition and structure, and population regulation and regeneration (Chambers et al. 2013).

The Great Basin shrub communities have high spatial and temporal variability in precipitation, both among years and within growing seasons. Nutrient availability is typically low but increases with elevation and closely follows moisture availability. The moisture resource supporting the greatest amount of plant growth is usually the water stored in the soil profile during the winter. The invasibility of plant communities is often linked to resource availability. Disturbance can decrease resource uptake due to damage or mortality of the native species and depressed competition or can increase resource pools by the decomposition of dead plant material following disturbance.

These salt-desert shrub communities are dominated by phreatophytes that depend for their water supply upon ground water that lies within reach of their roots. The plants on this site are halophytes, meaning they are highly tolerant of saline soil conditions. Halophytes tend to be smaller in size in areas with concentrated salt, and larger in less saline conditions (Flowers 1934). Halophyte seeds remain viable for long periods of time under saline conditions and tend to germinate in the spring when salt concentrations are reduced due to precipitation (Unger 1982, Gul and Weber 1999, Khan et al 2000). Alkali sacaton is a native long-lived, warm-season, densely tufted perennial bunchgrass ranging from 20 to 40 inches in height (Dayton 1931). It is considered a phreatophyte and a facultative wetland species in this region (USDA, NRCS 2015). It usually grows on saline soils but is not restricted to saline soils and can be found on nonsaline soils, rocky sites, open plains, valleys and bottom lands (Dayton 1931). Alkali sacaton has deep, coarse roots allowing it reach water tables at depths from 4 to 27 feet (Meinzer 1927). It reproduces from seeds and tillers and is a prolific seed producer. The seeds remain viable for several years because of the hard, waxy seed coats (USDA-Forest Service 1988).

Marcum and Kopec (1997) found inland saltgrass more tolerant of increased levels of salinity than alkali sacaton therefore dewatering and/or long term drought causing increased levels of salinity would create environmental conditions more favorable to inland saltgrass over alkali sacaton. Alkali sacaton is considered a facultative wet species in this region; therefore it is not drought tolerant. A lowering of the water table can occur with ground water pumping in these sites. This may contribute to the loss of deep rooted species such as greasewood and basin wildrye and an increase in rabbitbrush, shadscale (Atriplex confertifolia) and other species with the absence of drought.

This ecological site has low resilience to disturbance and resistance to invasion. Fire is not a typical disturbance in these sparsely vegetated communities. Changes in hydrology will affect plant communities; for example, lowering of the water table will decrease the herbaceous understory and eventually affect shrub species as well. If the soils in this DRG are excessively disturbed, soil blowouts followed by ponding may lead to the formation of small playettes and loss of vegetation for a time. There is a greater risk of this occurring in areas with high off-highway vehicle (OHV) use. It has been observed that soil disturbance appeared to enable vegetation recruitment (Blank et al 1998), but no further research has verified this. In the presence of non-native invasive weeds, soil disturbance could allow for further invasion. The introduction of annual weedy species, like halogeton (Halogeton glomeratus), may cause an increase in fire frequency and eventually lead to an annual state. One alternative stable state has been identified for this sit e.

Fire Ecology:

Historically, salt-desert shrub communities had sparse understories and bare soil in intershrub spaces, making these communities somewhat resistant to fire (Young 1983, Paysen et al. 2000). They may burn only during high fire hazard conditions; for example, years with high precipitation can result in almost continuous fine fuels, increasing fire hazard (West 1994, Paysen et al. 2000).

Alkali sacaton is tolerant of, but not resistant to fire. Recovery of alkali sacaton after fire has been reported as 2 to 4 years (Bock and Bock 1978). Alkali sacaton is tolerant of fire, but can be killed by severe fire. Summer fires are more detrimental than winter fires. Recovery is typically two to four years (Newman and Gates 2000).

Loren and Kadlec (1985) found that fire followed by flooding one week later eliminated saltgrass from a Utah salt marsh; they found that although fire did not kill the plant’s rhizomes, the grass was not able to recover after flooding. Without immediate flooding, saltgrass may actually increase in cover after fire (de Szalay and Resh 1997).

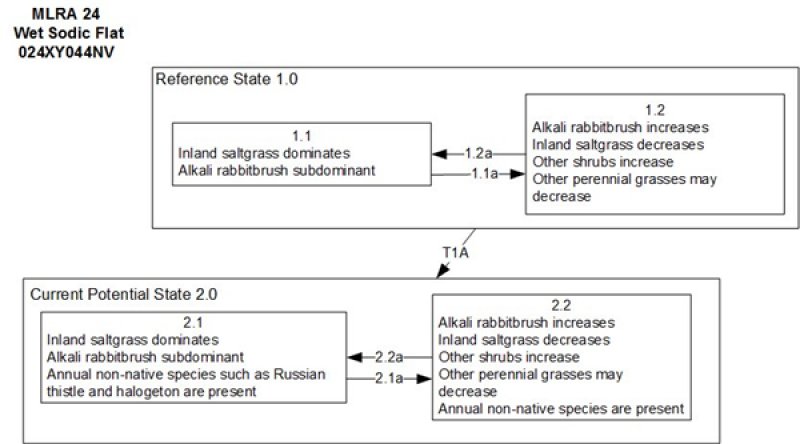

State and transition model

Figure 3. T Stringham 2016

Figure 4. Legend 8/2016

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

Ecosystem states

State 1 submodel, plant communities

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference State

The Reference State is representative of the natural range of variability under pristine conditions. The Reference State has two general community phases; a shrub-grass dominant phase and a shrub dominant phase. State dynamics are maintained by interactions between climatic patterns and disturbance regimes. Negative feedbacks enhance ecosystem resilience and contribute to the stability of the state. These include the presence of all structural and functional groups, low fine fuel loads, and retention of organic matter and nutrients. This site is very stable, with little variation in plant community composition. Plant community changes would occur in response to precipitation, long-term drought, or abusive grazing and would be reflected in annual production. Wet years will increase grass production, while normal dry conditions will reduce grass production and shrubs will dominate.

Community 1.1

Inland saltgrass

Figure 5. Wet Sodic Flat

The reference plant community is dominated by inland saltgrass and alkali rabbitbrush. Vegetation is distributed among low relief coppice mounds and salt-encrusted intermound depressions. Potential vegetative composition is about 45 percent grasses, 15 percent forbs and 40 percent shrubs. Approximate ground cover (basal and crown) is less than 10 percent.

Figure 6. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 76 | 113 | 177 |

| Shrub/Vine | 67 | 101 | 157 |

| Forb | 25 | 38 | 58 |

| Total | 168 | 252 | 392 |

Community 1.2

Shrub Dominated

Alkali rabbitbrush and iodinebush dominate saltgrass has decreased

Dominant plant species

-

iodinebush (Allenrolfea occidentalis), shrub

-

whiteflower rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus albidus), shrub

-

saltgrass (Distichlis spicata), grass

Pathway 1.1a

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Dry conditions increase soil surface salt content and allows iodinebush to dominate.

Pathway 1.2a

Community 1.2 to 1.1

High precipitation causes ponding on soil surface; increases alkali sacaton.

State 2

Current Potential State

This state is similar to the Reference State with two similar community phases. Ecological function has not changed, however the resiliency of the state has been reduced by the presence of invasive weeds. Non-natives may increase in abundance but will not become dominant within this state. These non-natives can be highly flammable and can promote fire where historically fire had been infrequent. Negative feedbacks enhance ecosystem resilience and contribute to the stability of the state. These feedbacks include the presence of all structural and functional groups, low fine fuel loads, and retention of organic matter and nutrients. Positive feedbacks reduce ecosystem resilience and stability of the state. These include the non-natives’ high seed output, persistent seed bank, rapid growth rate, ability to cross pollinate, and adaptations for seed dispersal.

Community 2.1

Grass Dominated

This plant community is dominated by inland saltgrass and alkali sacaton with patchy scattered shrubs including alkali rabbitbrush and black greasewood . Annual non-native species such as halogeton and Russian thistle are present and may be increasing within the community.

Community 2.2

Shrub dominated

This community is dominated by iodine bush, alkali rabbitbrush and other shrubs. Inland saltgrass and other perennial grasses have decreased. Annual non native plants are present and may be increasing.

Dominant plant species

-

whiteflower rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus albidus), shrub

-

iodinebush (Allenrolfea occidentalis), shrub

-

greasewood (Sarcobatus vermiculatus), shrub

-

saltgrass (Distichlis spicata), grass

-

alkali sacaton (Sporobolus airoides), grass

-

saltlover (Halogeton), other herbaceous

-

Russian thistle (Salsola), other herbaceous

Pathway 2.1a

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Dry conditions increases soil surface salt content and allows iodinebush to dominate

Pathway 2.2a

Community 2.2 to 2.1

High precipitation causes ponding on soil surface; increases alkali sacaton.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Introduction of non-native species such as halogeton and Russian thistle.

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Primary Perennial Grasses | 75–128 | ||||

| saltgrass | DISP | Distichlis spicata | 50–76 | – | ||

| 2 | Secondary Perennial Grasses | 6–20 | ||||

| squirreltail | ELEL5 | Elymus elymoides | 1–8 | – | ||

| alkaligrass | PUCCI | Puccinellia | 1–8 | – | ||

| alkali sacaton | SPAI | Sporobolus airoides | 1–8 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 3 | Primary Perennial Forbs | 12–26 | ||||

| cinquefoil | POTEN | Potentilla | 12–26 | – | ||

| 4 | Secondary Perennial Forbs | 6–20 | ||||

| buckwheat | ERIOG | Eriogonum | 1–8 | – | ||

| thelypody | THELY | Thelypodium | 1–8 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 5 | Primary Shrubs | 50–89 | ||||

| whiteflower rabbitbrush | CHAL9 | Chrysothamnus albidus | 50–89 | – | ||

| 6 | Secondary Shrubs | 39–59 | ||||

| iodinebush | ALOC2 | Allenrolfea occidentalis | 2–12 | – | ||

| rubber rabbitbrush | ERNAN5 | Ericameria nauseosa ssp. nauseosa var. nauseosa | 2–12 | – | ||

| greasewood | SAVE4 | Sarcobatus vermiculatus | 2–12 | – | ||

| seepweed | SUAED | Suaeda | 2–12 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

Livestock Interpretations:

This site has limited value for livestock grazing, due to the low forage production. Grazing management should be keyed to dominant grasses or palatable shrubs production. nadequate rest and recovery from defoliation favors inland saltgrass and causes a decrease in alkali sacaton. Alkali sacaton has been found to be sensitive to early growing season defoliation whereas late growing season and/or dormant season use allowed recovery of depleted stands (Hickey and Springfield 1966). Reduction in alkali sacaton facilitates the increase in bare ground and rabbitbrush, along with other shrubs and annual salt tolerant weedy species such as halogeton and fivehook bassia (Bassia hyssopifolia).

Kovalev and Krylova (1992) found that iodinebush is a possible feed for animals if mixed with other forage plants. Saltgrass is an important forage species and is relatively high in crude protein (Hanson et al 1976). It is grazed by both cattle and horses and it has a forage value of fair to good because it remains green when most other grasses are dry during periods of drought as well as being resistant to grazing and trampling (Skaradek and Miller 2010, Kartesz 1988).

Saltgrass's value as forage depends primarily on the relative availability of other grasses of higher nutritional value and palatability. It can be an especially important late summer grass in arid environments after other forage grasses have deceased. Saltgrass is rated as a fair to good forage species only because it stays green after most other grasses dry. Livestock generally avoid saltgrass due to its coarse foliage. Saltgrass is described as an increaser under grazing pressure. Baltic rush is described as a fair to good forage species for cattle. On average, Baltic rush palatability is considered medium to moderately low. Baltic rush is considered palatable early in the growing season when plants are young and tender, but as stems mature and toughen palatability declines.

Stocking rates vary over time depending upon season of use, climate variations, site, and previous and current management goals. A safe starting stocking rate is an estimated stocking rate that is fine tuned by the client by adaptive management through the year and from year to year.

Wildlife Interpretations:

Salt-desert shrub communities are relatively simple in terms of structure and species diversity but they serve as habitat for several wildlife species including reptiles, small mammals, birds and large herbivores (pronghorn antelope) (Blaisdell and Holmgren 1984).

Saltgrass provides cover for a variety of bird species, small mammals, and arthropods and is on occasion used as forage for several big game wildlife species. Baltic rush also provides food for several wildlife species and waterfowl. Baltic rush is an important cover species for a variety of small birds, upland game birds, birds of prey, and waterfowl.

Hydrological functions

Runoff is very high. Permeability is very slow. Hydrologic soil groups is D. Rills are none. Water flow patterns are rare to common dependent on site location relative to major inflow areas. Moderately fine to fine surface textures and physical crusts result in limited infiltration rates. The surface layer will normally crust and bake upon drying, inhibiting water infiltration and seedling emergence. Pedestals are none. There are typically no gullies associated with this site. Shrubs and deep-rooted perennial herbaceous bunchgrasses and/or rhizomatous grasses aid in infiltration.

Recreational uses

Aesthetic value is derived from the diverse floral and faunal composition and the colorful flowering of wild flowers and shrubs during the spring and early summer. This site offers rewarding opportunities to photographers and for nature study. This site has potential for upland and big game hunting.

Other products

The stems of Baltic rush were historically used by Native Americans as a foundation for coiled basketry.

Other information

Given its extensive system of rhizomes and roots which form a dense sod, saltgrass is considered a suitable species for controlling wind and water erosion. Baltic rush's production of deep and fibrous roots originating from a mass of coarse and creeping rhizomes makes it a valuable species for stabilizing streambanks and protecting against soil erosion.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

NASIS soil component data.

Type locality

| Location 1: Lander County, NV | |

|---|---|

| Township/Range/Section | T25N R48E S18 |

| UTM zone | N |

| UTM northing | 4432044 |

| UTM easting | 532610 |

| Latitude | 40° 2′ 16″ |

| Longitude | 116° 37′ 3″ |

| General legal description | E½ Approximately 7 miles west of Gund Ranch, on the western margins of playa at north end of Grass Valley, Lander County, Nevada. |

Other references

Blaisdell, J. P., and R. C. Holmgren. 1984. Managing Intermountain rangelands—salt-desert shrub ranges. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-163. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Ogden, UT.

Blank, R.R., J.A. Young, J.D. Trent, and D.E Palmquist. 1998. Natural history of a saline mound ecosystem. Great Basin Naturalist 58: 217-230.

Bock, C. E., and J. H. Bock. 1978. Response of birds, small mammals, and vegetation to burning sacaton grasslands in southeastern Arizona. Journal of Range Management Archives 31:296-300.

Caudle, D., J. DiBenedetto, M. Karl, H. Sanchez, and C. Talbot. 2013. Interagency ecological site handbook for rangelands. Available at: http://jornada.nmsu.edu/sites/jornada.nmsu.edu/files/InteragencyEcolSiteHandbook.pdf. Accessed 4 October 2013.

Chambers, J., B. Bradley, C. Brown, C. D’Antonio, M. Germino, J. Grace, S. Hardegree, R. Miller, and D. Pyke. 2013. Resilience to Stress and Disturbance, and Resistance to Bromus tectorum L. Invasion in Cold Desert Shrublands of Western North America. Ecosystems:1-16.

Dayton, W. 1937. Range plant handbook. USDA, Forest Service. Bull.

De Szalay, F. A. and V. H. Resh. 1997. Responses of wetland invertebrates and plants important in waterfowl diets to burning and mowing of emergent vegetation. Wetlands, 17(1), 149-156.

Flowers, S. 1934. Vegetation of the Great Salt Lake region. Botanical Gazette, 353-418.

Gul, B. and D.J. Weber. 2001. Seed bank dynamics in a Great Basin salt playa. Journal of Arid Environments 49:785-794.

Gul, B. and D. J. Weber. 1999. Effect of salinity, light, and temperature on germination in Allenrolfea occidentalis. Canadian Journal of Botany, 77(2), 240-246.

Hickey, Jr., W.C. and H.W. Springfield. 1966. Alkali sacaton: its merits for forage and cover. Journal of Range Management 19(2):71-74.

Kartesz, J.T. 1988. A flora of Nevada. University of Nevada, Reno, ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing.

Khan, M.A., B. Gul, and D. J. Weber. 2000. Germination responses of Salicornia rubra to temperature and salinity. Journal of Arid Environments, 45(3), 207-214.

Kovalev, V.M. and N.P. Krylova. 1992. Use of halophytes to improve arid pastures. Sel’skokhozyaistvennaya Biologiyha 4: 135-141.

Marcum, K.B. and D.H. Kopec. 1997. Salinity tolerance of turfgrasses and alternative species in the subfamily Chloridoideae (Poaceae). International Turfgrass Society Research Journal 8:735-742.

Meinzer, C.E. 1927. Plants as indicators of ground water. USGS Water Supply Paper 577.

Newman, S.D. and M. Gates. 2000. Plant guide for saltgrass Distichlis spicata (L.) Greene. USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service National Plant Data Center & the Louisiana State Office.

Paysen, T. E., R. J. Ansley, J. K. Brown, G. J. Gottfried, S. M. Haase, M. G. Harrington, M. G. Narog, S. S. Sackett, and R. C. Wilson. 2000. Fire in western shrubland, woodland, and grassland ecosystems. Wildland fire in ecosystems: Effects of fire on flora. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol 2:121-159.

Smith, L. M., and J.A. Kadlec. 1985. Comparisons of prescribed burning and cutting of Utah marsh plants. The Great Basin Naturalist. 45: 462-466.

Trent, J. D., R. R. Blank, and J. A. Young. 1997. Ecophysiology of the temperate desert halophytes: Allenrolfea occidentalis and Sarcobatus vermiculatus. Western North American Naturalist, 57(1), 57-65.

Ungar, I. A. 1982. Germination ecology of halophytes. In Contributions to the Ecology of Halophytes Springer Netherlands. Pp. 143-154.

USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service. 1998. Stream Visual Assessment Protocol. Technical Note 99-1. National Water and Climate Center. Portland, OR. 36pp.

Weber, D., B. Gul, and M. A. Khan. 2002. Halophytic characteristics and potential uses of Allenrolfea occidentalis. Pages 333-352 in R. Ahmad and K. A. Malik, editors. Prospects for Saline Agriculture. Springer Netherlands.

Young, R.P. 1983. Fire as a vegetation management tool in rangelands of the Intermountain region. In: Monsen, S.B. and N. Shaw (Eds). Managing Intermountain rangelands—improvement of range and wildlife habitats: Proceedings of symposia; 1981 September 15-17; Twin Falls, ID; 1982 June 22-24; Elko, NV. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-157. Ogden, UT. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. Pp. 18-31.

Contributors

GKB

TK Stringham

P NovakEchenique

Approval

Kendra Moseley, 3/06/2025

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) | Patti Novak-Echenique |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author | State Rangeland Management Specialist |

| Date | 03/19/2010 |

| Approved by | Kendra Moseley |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

Rills are none. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

Water flow patterns are rare to common depending on site location relative to major inflow areas. Moderately fine to fine surface textures and physical crusts result in limited infiltration rates. The surface layer will normally crust and bake upon drying, inhibiting water infiltration and seedling emergence. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

Pedestals are none. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

Bare Ground 70-80%. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

None -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

None -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Fine litter (foliage of grasses and annual & perennial forbs) expected to move distance of slope length during periods of intense summer convection storms or run in of early spring snow melt flows. Persistent litter (large woody material) will remain in place except during unusual flooding (ponding) events. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Soil stability values will range from 1 to 4. (To be field tested.) -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

Structure of soil surface is medium platy. Soil surface colors are light and soils are typified by an ochric epipedon. Organic matter is typically less than 2 percent. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

Shrubs and deep-rooted perennial herbaceous bunchgrasses and/or rhizomatous grasses aid in infiltration. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

Compacted layers are not typical. Angular blocky or massive subsurface layers are normal for this site and are not to be interpreted as compaction. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Reference Plant Community: Cool season, rhizomatous grassesSub-dominant:

Low-stature shrubs (alkali rabbitbrush) > deep-rooted, cool season, perennial bunchgrasses > shallow-rooted cool season, perennial bunchgrasses > deep-rooted, cool season, perennial forbs = fibrous, shallow-rooted, cool season, perennial and annual forbsOther:

Additional:

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

Little to no decadence. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Between plant interspaces (< 10-15%) and depth (± ¼ in.) -

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

For normal or average growing season (March thru May) ± 225 lbs/ac. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Increasers include rubber rabbitbrush and seepweed. Invaders include annual mustards, annual kochia, Russian thistle, halogeton, and knapweeds. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

All functional groups should reproduce in average (or normal) and above average growing season years.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.