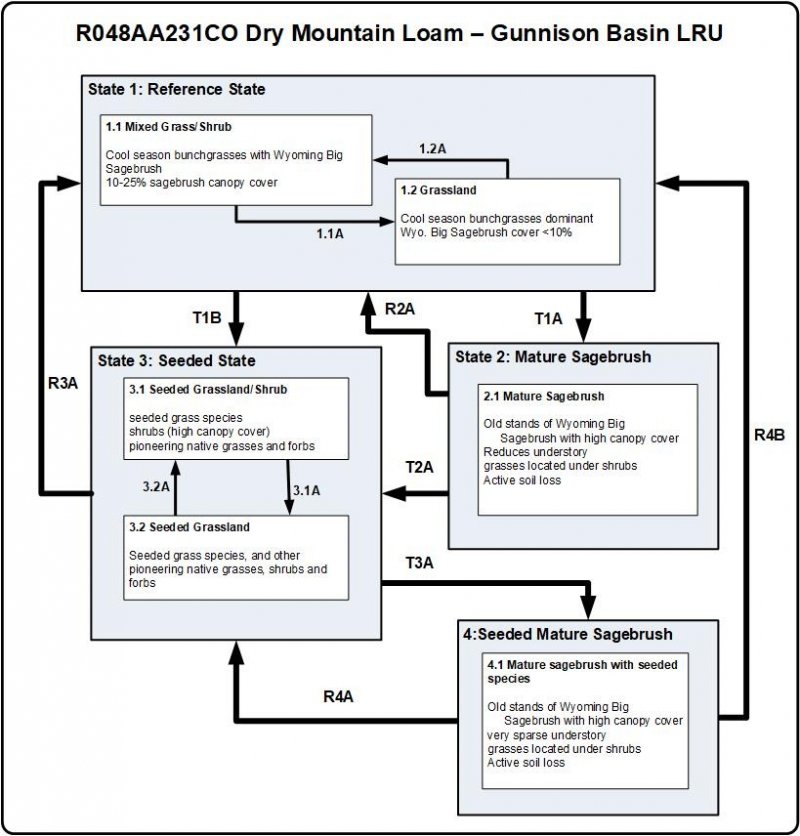

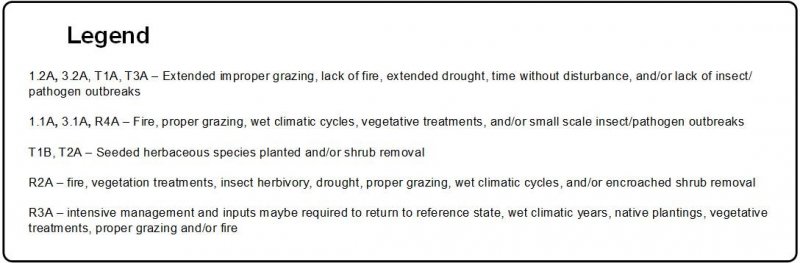

Ecological dynamics

The description of this site is based on the existing description of the Dry Mountain Loam range site (R48XY231CO) (USDA-SCS, 1975). The original site concept covered the entire MLRA 48A, which consists of the mountainous areas in Colorado. The concept for this ecological site covers primarily the high mountain areas in the Gunnison Basin area. The site has an aridic bordering on ustic soil moisture regime and a frigid temperature regime. This site is treeless; however, trees commonly are in the general vicinity. The reference state is a cool-season bunchgrass/shrub community. The appearance of the site is grassland with woody shrubs such as Wyoming big sagebrush and several forbs. Indian ricegrass, blue grama, pine needlegrass, needle and thread, prairie Junegrass, bottlebrush squirreltail, Sandberg bluegrass, muttongrass, and upland sedges provide the sparse grassland appearance. Wyoming big sagebrush is the dominant shrub. Yellow rabbitbrush may be present in small amounts, but the abundance will increase under some disturbances. Hood's phlox, winterfat, buckwheat, and fringed sage are common. Black sagebrush, snowberry, serviceberry, and antelope bitterbrush may be present in small amounts, especially at the edges of the modal concept of this site. The species composition and relative productivity may fluctuate from year to year depending on precipitation and other climatic factors.

The Gunnison Basin is in a climatic zone where pinyon (Pinus edulis) and juniper (Juniperus osteosperma) normally occur; however, the basin generally does not support these species because of its unique ecological characteristics. The basin does support intergradations of Wyoming big sagebrush and mountain big sagebrush. The Gunnison Basin is recognized for its unusual ecological characteristics, including absence of certain plants and vertebrates. Pinyon pine is rare in the basin, and western rattlesnake is absent. Winters are extremely cold, and the cold air settles into the basin. Also, this area is drier than other regions at similar elevations. It is thought that the temperature, moisture, and topography are responsible for the sagebrush-dominant plant communities in the Upper Gunnison Basin (Emslie et al., 2005).

The Gunnison Basin is in the transition zone from Wyoming big sagebrush to mountain big sagebrush. Wyoming big sagebrush generally is in areas that receive 7 to 11 inches of precipitation and are at an elevation of 4,500 to 6,000 feet, but in Colorado it may be in areas of well drained soils at an elevation of as high as 8,000 feet. Mountain big sagebrush is at an elevation of 6,800 to 8,500 feet. Bonneville big sagebrush, a hybrid of Wyoming big sagebrush and mountain big sagebrush, has been observed at the head of Long Gulch near Gunnison, Colorado, at an elevation of about 8,000 feet (between the boundaries of Wyoming big sagebrush and mountain big sagebrush (Winward, 2004). Ultraviolet fluorescent tests showed intergradations between the two subspecies in areas that receive 8 to 15 inches of precipitation (Goodrich et al., 1999). This ecological site is in areas that receive 10 to 14 inches of precipitation and are at an elevation of 7,200 to 8,200 feet; thus, both the subspecies and the hybrid may be in this site, depending on elevation and aspect. Mountain big sagebrush may grow in areas with Wyoming big sagebrush (Johnson, 2000); however, Wyoming big sagebrush tends to be associated with the Dry Mountain Loam ecological site (R048AA231CO) and mountain big sagebrush with the Mountain Loam site. The Dry Mountain Loam site is on the warmer, drier south and southwest aspects at the higher elevations, and the Mountain Loam site is on the cooler, wetter north and northeast aspects at the lower elevations.

The soils, topographic location, climate, and periodic drought and fire influence the stability of the reference state. The reference state is presumed to be the community encountered by European settlers in the early 1800's that developed under the prevailing climate over time. Grazing and browsing by wildlife also influenced the plant community. The resulting plant community is a cool-season bunchgrass/shrub community. Sagebrush communities in Colorado above an elevation of 8,500 feet are in relatively good condition and appear to be recovering slowly from the impacts of settlement in the west. Sagebrush communities below an elevation of 8,500 feet have been slower to recover (Winward, 2004).

Natural fire plays an important role in the function of most sites in high mountain valleys, especially the sagebrush communities. Fire stimulates growth of grasses such as needlegrasses and bluegrasses. It also helps to keep sagebrush stands from becoming too dense and invigorate other sprouting shrubs such as serviceberry and snowberry. Fire helps to maintain a balance among grasses, forbs, and shrubs. The dynamics of a plant community are improved by opening the canopy and stimulating growth of forbs, creating a mosaic of different age classes of species and a diverse composition of species in the communities. Other than Wyoming big sagebrush, the deep-rooted shrub species in the site are not easily damaged by fire (USDI-BLM, 2002). Shrubs that re-sprout, such as yellow rabbitbrush and snowberry, are suppressed for a period. This allows grasses to become dominant. If periodic fires or other brush control does not occur, sagebrush slowly increases in abundance and can become dominant.

Wyoming big sagebrush plant communities have lower productivity (less fuel loads), less ground cover, less crown cover of shrubs, and less diversity in species and structure than do mountain big sagebrush plant communities (Goodrich et al., 1999; West and Hassan, 1985; Evers et al., 2011; Johnson, 2000). Wyoming big sagebrush communities are less susceptible to fire than are mountain big sagebrush communities. Wyoming big sagebrush communities in the western United States have a fire return interval of 10 to 115 years (West and Hassan, 1985; Evers et al., 2011; Johnson, 2000). The fire return interval for Wyoming big sagebrush communities varies greatly depending precipitation and temperature; it is about 10 to 70 years in the Gunnison Basin.

Prior to 1850, the fires most likely consisted of many small- to medium-sized mosaic burns. Since 1980, the fires typically are a few very large fires (Evers et al., 2011). The change in the return interval and intensity of fires was cause by fire suppression and reduced fine fuel as a result of livestock grazing practices in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Proper treatment varies among sites due to differences in the composition and abundance of vegetation, soils, elevation, aspect, slope, and climate (McIver et al., 2010). Shrub management treatments other than fire may be needed periodically to maintain the balance of the community.

Several sagebrush taxa have been subject to die-off of shrubs in the past 10 to 15 years. The dominant factors are disease and pathogens. Disease and stem and root pathogens have caused die-off in dense, over-mature sagebrush stands throughout the west. Drought and heavy browsing in conjunction with disease and pathogens have caused complete die-off in other areas.

The major drivers of transitions from the reference plant community are continuous season-long grazing by ungulates and a decrease in the frequency of fires. As the population of ungulates increases and grazing exceeds the ability of plants to sustain under defoliation, the more palatable plants decline in stature, productivity, and density.

Limited cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) currently is in the Gunnison Basin. It is primarily along roadsides and in campgrounds. A study of cheatgrass seeds collected in the Gunnison Basin showed significant differences in germination characteristics regarding storage duration and temperature. This may indicate that cheatgrass is adapting to the colder temperatures in the Gunnison Basin, but further study is needed (Gasch and Bingham, 2006).

Variability in climate, soils, aspect, and complex biological processes results in differing plant communities. The species listed in this description are representative; not all occurring or potentially occurring species are listed. The species listed do not cover the full range of conditions and responses of the site. The state-and-transition model is based on available research, field observations, and interpretations by experts; changes may be needed as knowledge increases. The reference plant community is the interpretive community. This plant community evolved as a result of grazing, fire, and other disturbances such as drought. This site is well suited to grazing by domestic livestock and wildlife, and it is in areas that are properly managed by prescribed grazing.

State 1

Reference

Grass and minor amounts of woody plants such as sagebrush and several forbs make up most of the vegetative cover of this state. The site is treeless; however, trees commonly are in the general vicinity. The dominant grasses are native bluegrasses, Letterman’s needlegrass, pine needlegrass, and Indian ricegrass. Germander beardtongue, spiny phlox, and hollyleaf clover are the principal forbs. Sagebrush may become dominant if the understory species are over-defoliated. The optimum amount of ground cover is 35 percent. The species most likely to increase or invade are cheatgrass, blue grama, and rabbitbrush.

This state represents the community and function of the site prior to European settlement. Two dominant plant community phases are in the reference state. Fire and drought are natural disturbances that drive the pathways between the community phases. The site is subject to frequent periods of drought and fires of mixed intensity and frequency. The fire return interval (FRI) is 10 to 70 years in the more arid sagebrush areas (Wyoming big sagebrush) (Howard, 1999), and it is 15 to 40 years in the wetter mountain big sagebrush areas (Johnson, 2000). Sagebrush species less than 50 years old are easily killed by fire. Most forb species that re-sprout from a caudex, corm, bulb, rhizome, or rootstock recover rapidly following fire, and suffrutescent, low-growing or mat-forming forbs such as pussytoes and buckwheat may be severely damaged by fire (Miller and Eddleman, 2001). Needle and thread (Bunting, 1985), Indian ricegrass, and muttongrass are very palatable and can be over-defoliated. Wyoming big sagebrush, western wheatgrass, yellow rabbitbrush, Sandberg bluegrass (Bunting, 1985), prairie Junegrass (Bunting, 1985), blue grama, and needlegrasses are less palatable and can increase in abundance.

Sagebrush has tap roots, lateral roots and tertiary roots which allows this advantage in competition. Thinning sagebrush crowns may be necessary for understory establishment. Treatments methods need to fit the site’s specific needs. Sagebrush recruitment is episodic in 7-9 year cycles and sagebrush seeds have a limited viability after their second year. (Winward, 2004) Resting and/or deferring grazing after brush management promotes the establishment of grasses which in turn slows down sagebrush establishment. Grazing by species that prefer grasses and forbs will speed up the establishment of sagebrush.

When the density and canopy cover of sagebrush are near maximum for several decades, sagebrush can become competitive with the understory forbs and grasses. Grazing by species that prefer grasses and forbs will speed up the establishment of sagebrush. Sagebrush has tap, lateral, and tertiary roots that give it a competitive advantage. Thinning of sagebrush crowns may be necessary for establishment of the understory. Treatment methods should be adapted to the specific needs of the site. Sagebrush recruitment is episodic in 7- to 9-year cycles, and sagebrush seeds have limited viability after the second year (Winward, 2004). Resting or deferring grazing after brush management promotes the establishment of grasses and slows the establishment of sagebrush.

Community 1.1

Mixed Grass/Shrub

Figure 7. Reference plant community.

This plant community is characterized by Wyoming big sagebrush and Indian ricegrass. Based on annual production, the potential vegetation is about 40 to 60 percent grasses and grasslike plants, 5 to 15 percent forbs, and 25 to 35 percent woody plants. Prolonged grazing during periods of drought can result in an increase in subdominant grass species and shift the plant community to mixed grasses rather than dominantly Indian ricegrass. Primary grasses include needle and thread, muttongrass, western wheatgrass, pine needlegrass, Indian ricegrass, and blue grama. Major forbs include redroot buckwheat, spiny phlox (Hood’s phlox), and scarlet globemallow.

The plant community is diverse, stable, and productive under normal precipitation. Litter is properly distributed and little is moved offsite. The natural plant mortality rate is low. Forbs are a dynamic component of this site; production can vary greatly depending on the annual precipitation. Community dynamics, the nutrient and water cycles, and energy flow function properly in this community. The community can be maintained by properly management of grazing, including adequate deferment during the growing season to allow for establishment of grasses and recovery of the vigor of stressed plants. This community is resistant to many disturbances, but it may be affected by continuous overgrazing, tillage, urban sprawl, and oil and gas infrastructures and other developments.

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type |

Low

(lb/acre) |

Representative value

(lb/acre) |

High

(lb/acre) |

| Grass/Grasslike |

285 |

420 |

550 |

| Shrub/Vine |

165 |

250 |

340 |

| Forb |

50 |

80 |

110 |

| Total |

500 |

750 |

1000 |

Table 6. Ground cover

| Tree foliar cover |

0%

|

| Shrub/vine/liana foliar cover |

10-25%

|

| Grass/grasslike foliar cover |

15-25%

|

| Forb foliar cover |

3-10%

|

| Non-vascular plants |

0-2%

|

| Biological crusts |

0-2%

|

| Litter |

15-30%

|

| Surface fragments >0.25" and <=3" |

15-25%

|

| Surface fragments >3" |

0-5%

|

| Bedrock |

0%

|

| Water |

0%

|

| Bare ground |

25-40%

|

Table 7. Canopy structure (% cover)

| Height Above Ground (ft) |

Tree |

Shrub/Vine |

Grass/

Grasslike |

Forb |

| <0.5 |

– |

10-25% |

10-25% |

3-10% |

| >0.5 <= 1 |

– |

10-25% |

5-15% |

1-5% |

| >1 <= 2 |

– |

10-20% |

0-5% |

1-5% |

| >2 <= 4.5 |

– |

0-10% |

0-2% |

0-1% |

| >4.5 <= 13 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >13 <= 40 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >40 <= 80 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >80 <= 120 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| >120 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Community 1.2

Grassland

Figure 10. Area of community 1.2 ten years after a fire.

This community is characterized by an increase in the abundance of grasses and forbs following a disturbance such as fire. Recurring fires at an internal of less than 10 years maintain the grassland and prevent establishment of sagebrush. Five to ten years is needed for sagebrush to establish after a fire and 15 to 20 years for the density and cover to return to pre-burn levels (Nelle et al., 2000). Severe fires can slow the re-establishment and dominance of Wyoming big sagebrush. The maximum total production of grass herbage is reached 2 to 5 years after burning, but the increased grass cover is short lived. Production declines as the abundance of sagebrush and other shrub species increases. The forb cover has the highest biomass 5 to 15 years after burning (Nelle et al., 2000).

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

The natural fire return interval and fire intensity characterize this pathway (McIver, et al., 2010). Shrub management including applying herbicides and mowing can be used to mimic this pathway. Drought and prescribed grazing or improper grazing can influence the time frame of the pathway. This pathway can be a result of high use by wildlife in winter and browsing by livestock. Short periods of drought in winter and early in spring facilitate an increase in the understory. Grasses respond quicker to moisture received in midsummer and late in summer than do shrubs.

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

This pathway is characterized by the natural fire return interval. Improper grazing can decrease the abundance of the understory and increase the sagebrush canopy, which shortens the time to transition back to reference community phase 1.1. Extended drought and improper grazing can change the time frame for this pathway. Improper browsing and suitable grazing of the understory species, frequent fires prior to seed set of the sagebrush but after seed set of the understory, and large-scale die-off of sagebrush from insects or pathogens can cause this pathway (Evers et al., 2011).

State 2

Mature Sagebrush

State 2 is a sagebrush-dominant plant community. This state has an increase in shrub cover and a decrease in understory cover as compared to state 1. This sagebrush community is a single-aged stand. The abundance of Sandberg bluegrass and western wheatgrass is increased and that of Indian ricegrass and prairie Junegrass is decreased. The abundance of low shrubs such as yellow rabbitbrush, spineless horsebrush, and broom snakeweed also is increased, replacing some of the herbaceous component in the understory. The diversity of species is lower in this state than in state 1. Improper grazing management practices that decrease the abundance of the deep-rooted understory species can lead to compaction of the soil, increased susceptibility to erosion, decreased organic matter in the soil, and increased exposure of the soil.

Community 2.1

Sagebrush Dominated

Figure 12. Area of sagebrush-dominant community 2.1.

This state has a very dense stand of Wyoming big sagebrush and little, if any, understory. A few remnant herbaceous plants are in the understory but not enough to re-seed the site if it is disturbed. This state is comprised dominantly of shrubs, including Wyoming big sagebrush, yellow rabbitbrush, and prickly pear cactus. The dominant forb is Hood’s phlox. Trace amounts of Sandberg bluegrass, pine needlegrass, and Letterman’s needlegrass may be present. The minimal understory helps to suppress low-intensity fires because of a lack of fine fuel; however, high-intensity crown fires may occur because of the high canopy cover. An increase in the sagebrush canopy may be due to lack of disturbance such as wildfire. Cumulating effects of degrading sagebrush habitats include higher susceptibility to erosion and sedimentation, decreased water quality, decreased forage for domestic livestock, and decreased habitat for wildlife species (McIver et al., 2010).

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

State 3

Seeded

This state is characterized by sagebrush removal due to fire or shrub management treatments, which may include chaining, disking, and mowing. The community dynamics are similar those of the reference state. This state could persist for long periods. Sagebrush will start to re-establish when the conditions are favorable. This site is seeded to perennial species such as crested wheatgrass and Russian wildrye.

Community 3.1

Seeded Grassland/Shrub

Figure 14. Area of crested wheatgrass.

This community consists dominantly of seeded perennial grasses such as Russian wildrye and crested wheatgrass and some Wyoming big sagebrush establishing as the overstory species. The sagebrush is seeded from adjacent areas or the seedbanks after the grasses are seeded. Small amounts of Sandberg bluegrass, western wheatgrass, pine needlegrass, and Letterman’s needlegrass slowly become established in this community phase. The sagebrush canopy is 1 to 15 percent, and the herbaceous understory cover is 30 to 40 percent.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Community 3.2

Seeded Grassland

This community is characterized by introduced perennial grasses such as crested wheatgrass and Russian wildrye. Fire or other shrub management is needed to maintain this community phase.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Pathway 3.1A

Community 3.1 to 3.2

Proper grazing and wet periods can move this community toward phase 3.1. Shrub management, including use of herbicides, can be used to mimic the pathway. Mortality of establishing sagebrush from pathogens and insects can influence this pathway. Short-term drought in winter and early in spring will facilitate an increase in the understory. Grasses respond quicker to moisture received in midsummer and late in summer than do shrubs.

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|

Pathway 3.2A

Community 3.2 to 3.1

The natural pathway over time without fire. Improper grazing of the understory species and little, if any, seedling establishment or regeneration results in an increased canopy cover of sagebrush.

State 4

Seeded Mature Sagebrush

State 4 is a sagebrush-dominant community. The abundance of shrub cover is increased and that of the understory is decreased. The sagebrush consists of an even-structured, single-aged stand. The abundance of introduced species is decreased in this community. The abundance of low shrubs such as yellow rabbitbrush and spineless horsebrush also is increased, replacing some of the herbaceous component in the understory. The diversity of species is low. Improper grazing management leads to a decrease in deep-rooted species in the understory.

Community 4.1

Sagebrush Dominated with Introduced Species

This community has more than 45 percent live canopy cover of Wyoming big sagebrush. Little, if any, grasses and forbs are in the interspaces. The grasses and forbs that remain are directly under the canopy of the Wyoming big sagebrush. Soil erosion is active.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Improper grazing for extended periods during the growing season can reduce the amount of fine fuel in the understory, which favors sagebrush encroachment. Lack of fire over time can cause this transition (McIver et al., 2010). Extended periods of drought and lack of insect and pathogen activity can result in a single-aged stand of sagebrush. This transition is characterized by a decrease in the understory and an increase in the amount of bare ground between the shrubs and other evidence of soil erosion. The depletion of fine fuel due to improper grazing shifts the fire regime from relatively frequent fires of low to mixed severity (10- to 70-year mean fire return interval) to less frequent fires of high severity (more than 70-year mean fire return interval).

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

Historically, this transition has resulted from a catastrophic wildfire but it can be induced by human activity (shrub management or prescribed burning). It is seeded with introduced species. Short-term loss of topsoil and a reduction in the water-holding capacity in the upper part of the soil occur, and the diversity of species is decreased.

Restoration pathway R2A

State 2 to 1

Proper grazing, wet periods, fire after seed set of the understory, and small-scale mortality of shrubs from insects and pathogens can move this community toward a more diverse understory and away from a dense, single-aged stand of sagebrush (Evers et al., 2011). Shrub management, including application of herbicides and prescribed burning, and seeding of native species after burning can be used to mimic this pathway.

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Range Planting |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|

Transition T2A

State 2 to 3

This transition is human induced through shrub management, prescribed burning, and reseeding with introduced species after a catastrophic wildfire.

Restoration pathway R3A

State 3 to 2

The site may be restored to resemble the Indian ricegrass and Wyoming big sagebrush community in the reference state by seeding commercial mixtures of native grasses, forbs, and shrubs. Selective removal of introduced species also may be needed. If properly managed, a semblance of the diversity and complexity of the reference state can be restored. This restoration pathway is intensive if attempted on a large scale.

Transition T3A

State 3 to 4

Improper grazing for an extended period and lack of fire are the main drivers of this transition. Extended periods of drought also can affect the productivity of the understory. These factors can return the community to a mature, single-aged shrub community that has a few seeded introduced species in the understory, mostly under the canopy of the shrubs.

Restoration pathway R4A

State 4 to 3

Fire and wet periods can cause the mature, single-aged shrub community to return to a grassland state if proper grazing management is implemented and sufficient seed is in the seed bank to regenerate the understory species. If sufficient seed or mature plants are not available for this pathway, reseeding may be needed. Shrub management practices such as prescribed burning, prescribed grazing, and seeding could help to move the community from state 4 to state 3.

| Brush Management |

|

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Fence |

|

| Range Planting |

|

| Watering Facility |

|

| Upland Wildlife Habitat Management |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|