Ecological dynamics

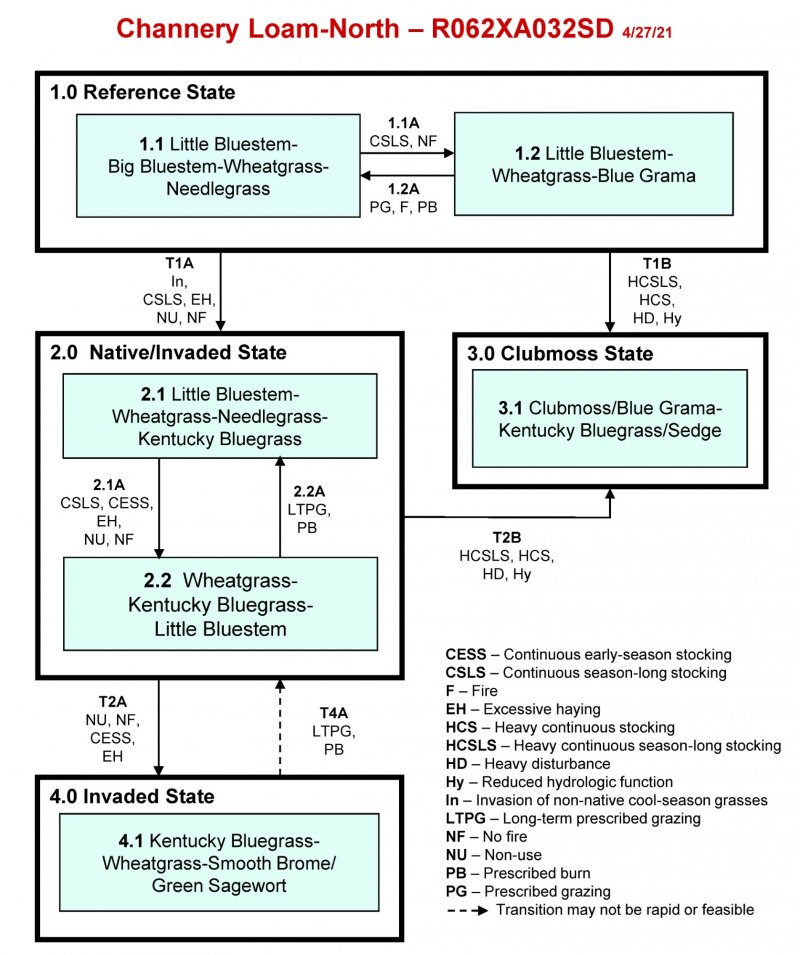

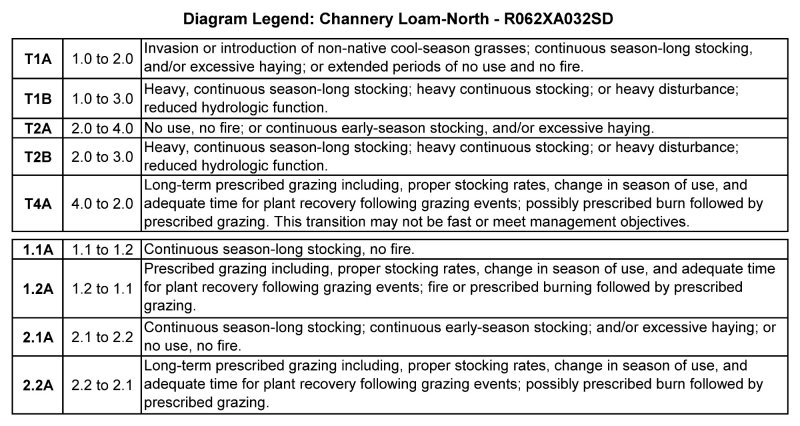

The Channery Loam - North ecological site evolved under Black Hills climatic conditions; light to severe grazing by bison, elk, insects, and small mammals; sporadic, natural or human-caused wildfire (often of light intensities); and other biotic and abiotic factors that typically influence soil and site development. Changes occur in the plant communities due to short-term weather variations, effects of native and exotic plant and animal species, and management actions. Severe disturbances, such as periods of well below-average precipitation, severe defoliation, excessive haying, or non-use and no fire can cause significant shifts in plant communities and species composition.

The natural fire regime maintained this site as a grassland and the plant communities were free of pine encroachment and invasion of non-native cool-season grasses. Fire, or the lack of fire, grazing, haying, drought, and the introduction of non-native cool-season grasses are major drivers that shape this site as well as adjacent ecological sites.

Continuous season-long stocking (e.g., the typical the full growing season, May through October) without change in season of use or adequate recovery periods following grazing events will cause departure from the Little Bluestem-Big Bluestem-Wheatgrass-Needlegrass Plant Community (1.1). Little bluestem, wheatgrass, and needlegrass will increase initially and then begin to decrease. Big bluestem and sideoats grama will decrease in frequency and production and shortgrasses and sedges will increase.

Extended periods of non-use and lack of fire will result in excessive litter and a plant community dominated by cool-season grasses such as western wheatgrass, and non-native cool-season grasses.

Heavy, continuous season-long stocking, heavy continuous stocking, or heavy disturbance can transition any plant community to a plant community dominated by clubmoss.

Long-term no fire does not appear to result in significant encroachment of conifer trees on this site as it will on adjacent ecological sites. Further investigation will be required to understand and quantify this observation.

Interpretations are primarily based on the Little Bluestem-Big Bluestem-Wheatgrass-Needlegrass Plant Community (1.1). It has been determined by study of rangeland relic areas, areas protected from excessive disturbance, and areas under long-term rotational grazing regimes. Trends in plant community dynamics ranging from heavily grazed to lightly grazed areas, seasonal use pastures, and historical accounts also have been used. Plant community phases, states, transitional pathways, and thresholds have been determined through similar studies and experience.

The following is a State-and-Transition diagram that illustrates the common plant communities that can occur on the site and the transition pathways between communities. The ecological processes will be discussed in more detail in the plant community descriptions following the diagram.

State 1

Reference State

The Reference State represents what is believed to show the natural range of variability that dominated the dynamics of the ecological site prior to European settlement. This site in the Reference State (1.0) is dominated by warm-season grasses, with cool-season grasses being subdominant.

In pre-European times, the primary disturbance mechanisms for this site in the reference condition included occasional fire and grazing by large ungulates. Timing of fires and grazing coupled with weather events dictated the dynamics that occurred within the natural range of variability. Taller cool- and warm-season grasses would have declined and a corresponding increase in short statured grass and grass-like species would have occurred.

Today, a similar state can be found on areas that are properly managed with grazing and/or prescribed burning, and sometimes on areas receiving occasional short periods of rest.

Characteristics and indicators. The Reference State (1.0) is dominated by mid- and tall-statured warm-season grasses and subdominant cool-season bunchgrasses and rhizomatous wheatgrass. The Reference State is very susceptible to invasion of non-native cool-season grasses and the expansion of clubmoss.

Resilience management. Management strategies to sustain the Reference State (1.0) include, setting proper stocking rates, monitoring utilization of key species, providing adequate time for plant recovery following grazing events or other disturbance events (e.g. fire, drought, hailstorms), and maintaining soil and site stability. The use of prescribed burning may be effective at limiting or minimizing the invasion and establishment of non-native cool-season grasses.

Community 1.1

Little Bluestem-Big Bluestem-Wheatgrass-Needlegrass

Figure 9. Channery Loam - PCP 1.1

Interpretations are based primarily on the Little Bluestem-Big Bluestem-Wheatgrass-Needlegrass Plant Community. This is also considered to be the Reference Plant Community (1.1).

The potential vegetation is about 85 percent grasses or grass-like plants, 10 percent forbs, 5 percent shrubs. The community is dominated by warm-season grasses, with cool-season grasses being subdominant. The major grasses include little bluestem, big bluestem, western wheatgrass, bearded wheatgrass, and needle and thread. Other grasses include porcupine grass, plains muhly, prairie dropseed, and a variety of other grass and grass-like species. Common forbs include, goldenrod, dotted gayfeather, western yarrow, and white sagebrush (cudweed sagewort). Prairie rose, leadplant, and fringed sagewort are common shrubs.

This plant community is resilient and well adapted to the Northern Great Plains climatic conditions. The diversity in plant species allows for high drought tolerance. This is a sustainable plant community in regard to site and soil stability, watershed function, and biologic integrity.

Resilience management. Management strategies to sustain this plant community include setting proper stocking rates, monitoring utilization of key species, providing adequate time for plant recovery following grazing events or other disturbance events, and maintaining soil and site stability.

Dominant plant species

-

prairie sagewort (Artemisia frigida), shrub

-

leadplant (Amorpha canescens), shrub

-

rose (Rosa), shrub

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), grass

-

slender wheatgrass (Elymus trachycaulus), grass

-

western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), grass

-

needle and thread (Hesperostipa comata ssp. comata), grass

-

prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis), grass

-

white sagebrush (Artemisia ludoviciana), other herbaceous

-

dotted blazing star (Liatris punctata), other herbaceous

-

goldenrod (Solidago), other herbaceous

-

prairie clover (Dalea), other herbaceous

-

scurfpea (Psoralidium), other herbaceous

-

western yarrow (Achillea millefolium var. occidentalis), other herbaceous

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type |

Low

(lb/acre) |

Representative value

(lb/acre) |

High

(lb/acre) |

| Grass/Grasslike |

1460 |

1755 |

2010 |

| Forb |

100 |

210 |

350 |

| Shrub/Vine |

40 |

125 |

215 |

| Tree |

0 |

10 |

25 |

| Total |

1600 |

2100 |

2600 |

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Community 1.2

Little Bluestem-Wheatgrass-Blue Grama

This plant community developed under continuous season-long grazing (grazing at moderate to moderately heavy stocking levels for extended portions of the growing), or from over utilization during extended drought periods, and the lack of periodic fire.

The potential plant community is made up of approximately 85 percent grasses and grass-like species, 10 percent forbs, and 5 percent shrubs. Dominant grasses include little bluestem, western and bearded wheatgrass, blue grama and upland sedges. Grasses and grass-likes species of secondary importance include sideoats grama, needle and thread, porcupine grass, and prairie Junegrass. Forbs commonly found in this plant community include white sagebrush (cudweed sagewort), goldenrod, white prairie aster, and scurfpea. Shrubs will include leadplant, rose, and fringed sagewort.

When compared to the Reference Plant Community (1.1), little bluestem, blue grama, wheatgrass, and sedge have increased. Tall warm-season grasses have decreased, and vegetative production has also declined. Needlegrasses will persist in this phase. This plant community is moderately resistant to change. The herbaceous species present are well adapted to grazing; however, species composition can be altered through continued overgrazing. If the herbaceous component is intact, it tends to be resilient if the disturbance is not long-term.

Resilience management. Management strategies to sustain this plant community include setting proper stocking rates, monitoring utilization of key species, providing adequate time for plant recovery following grazing events or other disturbance events, and maintaining soil and site stability.

Dominant plant species

-

prairie sagewort (Artemisia frigida), shrub

-

rose (Rosa), shrub

-

leadplant (Amorpha canescens), shrub

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), grass

-

blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), grass

-

threadleaf sedge (Carex filifolia), grass

-

white sagebrush (Artemisia ludoviciana), other herbaceous

-

goldenrod (Solidago), other herbaceous

-

scurfpea (Psoralidium), other herbaceous

-

western yarrow (Achillea millefolium var. occidentalis), other herbaceous

-

hairy false goldenaster (Heterotheca villosa), other herbaceous

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

•Continuous season-long stocking: repeated grazing at moderate to moderately heavy stocking levels, during the typical growing season (May through October), without change in season of use or adequate recovery periods following grazing events.

•Extended periods of drought in combination with heavy stocking that is above available levels of plant vegetative production.

•These mechanisms singly, or in combination, will shift the Little Bluestem-Big Bluestem-Wheatgrass-Needlegrass Plant Community (1.1) to the Little Bluestem-Wheatgrass-Blue Grama Plant Community (1.2).

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

•Prescribed grazing providing, proper stocking rates, alternating season of use, and adequate recovery periods following grazing events.

•Periodic light to moderate grazing possibly including periodic rest (non-use) following drought or fire.

•Possible prescribed burning.

•These mechanisms singly, or in combination, will shift the Little Bluestem-Wheatgrass-Blue Grama Plant Community (1.2) to the Little Bluestem-Big Bluestem-Wheatgrass-Needlegrass Plant Community (1.1).

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|

State 2

Native/Invaded State

The Native/Invaded State is dominated by native cool- and warm-season grasses, and subdominant non-native cool-season grasses. The non-native cool-season grasses will make up to 15 percent of the total annual production. This state can be found on areas that would appear to be properly managed with grazing and possibly periodic prescribed burning. This state represents what is most typically found on this ecological site.

This state is the result of long-term continuous season-long stocking at light to moderate stocking levels, during the typical growing season (May through October); excessive haying; or extended periods of non-use, no fire, and the build-up litter. If the native cool-season grasses decline, a corresponding increase of non-native cool-season grasses can occur. The non-native cool-season grasses will include, Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, cheatgrass, and field brome.

Characteristics and indicators. Non-native cool-season grasses will make up to 15 percent of the total annual production in the Native/Invaded State (2.0).

Resilience management. Management strategies to sustain the Native/invaded State (2.0) include, setting proper stocking rates, monitoring utilization of key species, providing adequate time for plant recovery following grazing events or other disturbance events (e.g. fire, drought, hailstorms), and maintaining soil and site stability. The use of prescribed burning may be effective at limiting or minimizing the expansion of non-native cool-season grasses on the ecological site. Because of the adaptability and persistence of these non-native grass species, a recovery to the Reference State (1.0) is highly unlikely.

Community 2.1

Little bluestem-Wheatgrass-Needlegrass-Kentucky Bluegrass

Plant Community 2.1 will closely resemble the Reference Plant Community (1.1). The major difference is that non-native cool-season grasses have invaded and established on the site and make up to 15 percent (by weight) of the plant community. The potential vegetation is about 85 percent grass and grass-like plants, 10 percent forbs, 5 percent shrubs.

Warm-season grasses and cool-season grasses are codominant. The primary warm-season grasses include little bluestem, sideoats grama, and blue grama. The cool-season grasses include western wheatgrass, slender wheatgrass, bearded wheatgrass, needle and thread, and Kentucky bluegrass and/or other non-native cool-season grasses. Forbs are common and diverse. Shrubs include wild rose, leadplant, and fringed sagewort.

This plant community is productive and resilient to disturbances such as drought and fire. It is a sustainable plant community regarding soil and site stability, watershed function, and biological integrity. Management strategies must include techniques that minimize the increase of Kentucky bluegrass and other non-native cool-season grasses, or this plant community may become at-risk.

Resilience management. Management strategies to sustain this plant community include setting proper stocking rates, monitoring utilization of key species, providing adequate time for plant recovery following grazing events or other disturbance events, and maintaining soil and site stability. Prescribed burning may be beneficial in maintaining a relative low level of non-native cool-season grasses.

Dominant plant species

-

rose (Rosa), shrub

-

leadplant (Amorpha canescens), shrub

-

prairie sagewort (Artemisia frigida), shrub

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), grass

-

slender wheatgrass (Elymus trachycaulus), grass

-

needle and thread (Hesperostipa comata ssp. comata), grass

-

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), grass

-

goldenrod (Solidago), other herbaceous

-

western yarrow (Achillea millefolium var. occidentalis), other herbaceous

-

white sagebrush (Artemisia ludoviciana), other herbaceous

-

scurfpea (Psoralidium), other herbaceous

-

prairie clover (Dalea), other herbaceous

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Community 2.2

Wheatgrass-Kentucky Bluegrass-Little bluestem

Figure 14. Channery Loam - PCP 2.2

This plant community developed under continuous season-long grazing, or continuous early-season seasonal grazing with no change in season of use; excessive haying possibly in combination with grazing; or extended periods of non-use and no fire, allowing for excessive litter buildup.

This plant community phase is made up of approximately 85 percent grass and grass-like plants, 10 percent forbs, and 5 percent shrubs. The community is dominated by cool-season grasses, with much of the warm-season grass components replaced by Kentucky bluegrass and other non-native cool-season grasses. The dominant native cool-season grasses include western wheatgrass, slender and bearded wheatgrass. Kentucky bluegrass or other non-native cool-season grasses can make up 10 to 25 percent (by weight) of the plant community. The dominant warm-season grass is remnant stands of little bluestem. Production can be variable but will typically be less than plant community 2.1. The period when palatability is high, is relatively short, as Kentucky bluegrass matures early in the growing season.

This plant community may become at-risk of transitioning to the Invaded State (4.0).

Resilience management. Management strategies to sustain this plant community include setting proper stocking rates, monitoring utilization of key species, providing adequate time for plant recovery following grazing events or other disturbance events, and maintaining soil and site stability. Prescribed burning may be an option to reduce the amount of Kentucky bluegrass and other non-native cool-season grasses.

Dominant plant species

-

prairie sagewort (Artemisia frigida), shrub

-

rose (Rosa), shrub

-

field sagewort (Artemisia campestris), shrub

-

western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), grass

-

slender wheatgrass (Elymus trachycaulus), grass

-

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), grass

-

little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), grass

-

western yarrow (Achillea millefolium var. occidentalis), other herbaceous

-

white sagebrush (Artemisia ludoviciana), other herbaceous

-

scurfpea (Psoralidium), other herbaceous

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Pathway 2.1A

Community 2.1 to 2.2

•Continuous season-long stocking including, repeated grazing at moderate to moderately heavy stocking levels, during the typical growing season (May through October), without change in season of use or adequate recovery periods following grazing events.

•Continuous early-season stocking including, repeated moderate to moderately heavy stocking levels, during the spring, early cool-season growing season (April through early June), without change in season of use or adequate recovery periods following grazing events.

•Excessive haying includes annual mechanical harvesting of rangeland plant communities without adequate time for plant recovery. Leaving inadequate post-harvest stubble height for retention of photosynthetic leaf area, nor providing adequate insulation cover from extreme heat or cold will result in a decline in plant health and vigor and increased plant mortality. Desirable grasses and forbs for forage and wildlife cover will decrease, and other less desirable plants will increase.

•Extended periods of no use and no fire results in heavy litter buildup which favors non-native cool-season grasses such as Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and other non-native species, and the reduction of native warm-season grasses.

•These mechanisms, singly or in combination, will shift the Little Bluestem-Wheatgrass-Needlegrass-Kentucky Bluegrass Plant Community (2.1) to the Wheatgrass-Kentucky Bluegrass-Little Bluestem Plant Community (2.2).

Pathway 2.2A

Community 2.2 to 2.1

•Long-term prescribed grazing including proper stocking rates, change in season of use, and adequate time for plant recovery following grazing events.

•Prescribed burning to decrease the amount of non-native cool-season grasses.

•These mechanisms, singly or in combination, may shift the Wheatgrass-Kentucky Bluegrass-Little Bluestem Plant Community (2.2) to the Little Bluestem-Wheatgrass-Needlegrass- Kentucky Bluegrass Plant Community (2.1).

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|

State 3

Clubmoss State

Clubmoss (lesser spikemoss) forms a dense sod-matt in this state. It will occupy areas of plant communities that are disturbed or degraded due to long-term repeated disturbances. Clubmoss cover is often 25 percent or greater. This sod-matt alters the normal hydrologic function of the site and creates a more arid microclimate, resulting in extreme competition for available moisture. The vigor and productivity of other native grasses are dramatically reduced.

Characteristics and indicators. Clubmoss expands in disturbed or degraded areas within a plant community. The foliar cover is often 25 percent or greater. It will alter the normal hydrologic function of this site, with increased runoff and less infiltration rates.

Resilience management. A restoration or transition pathway from the Clubmoss State (3.0) to another State is unlikely, except on small areas where channers are deeper in the profile. Most areas within this ecological site contain exposed schist channers, and the use of mechanical treatment to break up the clubmoss may not be practical or economical. Herbicides and/or intense short-term hoof action may be effective in reducing clubmoss in the plant community, but the results may be mixed, and not meet management objectives.

Community 3.1

Clubmoss/Blue Grama-Kentucky Bluegrass/Sedge

Figure 16. Channery Loam - PCP 3.1 - Clubmoss

Figure 17. Channery Loam - PCP 3.1 - Clubmoss root mat

This plant community is the results of heavy, continuous season-long stocking, heavy continuous stocking, heavy disturbance, and reduced hydrologic function.

This plant community is dominated by a dense sod of clubmoss, blue grama, and upland sedges. There will also be minor amounts of native cool-season grasses, forbs, and shrubs that persist in the plant community. Because infiltration is greatly reduced, tall, and mid-statured grasses will lack vigor and vegetative production. Cool-season grasses can include, Sandberg bluegrass, wheatgrass, needle and thread, prairie Junegrass, bottlebrush squirreltail, and Kentucky bluegrass. Common forbs will include goldenrod, scurfpea, and western yarrow. Shrubs will include green sagewort, and fringed sagewort.

Resilience management. The Clubmoss/Blue Grama-Kentucky Bluegrass/Sedge plant community is very resistant to change. The altered hydrology gives clubmoss, blue grama, and upland sedges a competitive advantage over other native species from expanding and establishing on the site. Initially runoff rates are low but then increase as clubmoss becomes saturated.

Dominant plant species

-

prairie sagewort (Artemisia frigida), shrub

-

field sagewort (Artemisia campestris), shrub

-

blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), grass

-

threadleaf sedge (Carex filifolia), grass

-

Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), grass

-

prairie Junegrass (Koeleria macrantha), grass

-

Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda), grass

-

western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), grass

-

needle and thread (Hesperostipa comata ssp. comata), grass

-

lesser spikemoss (Selaginella densa), other herbaceous

-

western yarrow (Achillea millefolium var. occidentalis), other herbaceous

-

goldenrod (Solidago), other herbaceous

-

scurfpea (Psoralidium), other herbaceous

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

State 4

Invaded State

The Invaded State (4.0) is the result long-term no use, and no fire, or continuous early-season stocking and/or excessive haying, which has allowed Kentucky bluegrass and other non-native cool-season grasses to dominate the site. No use and no fire will cause an excessive thatch layer to develop. Plant litter accumulation tends to favor the more shade-tolerant introduced grass species. Hydrological function can be reduced as the dense root mats created by Kentucky bluegrass reduces water infiltration. The nutrient cycle can also be impaired, resulting in a higher level of nitrogen which also favors the introduced species. Kentucky bluegrass is very resistant to overgrazing and will expand under heavy continuous grazing and out-compete other native species that are not as adapted to overgrazing.

Characteristics and indicators. Non-native cool-season grasses will make up 30 percent or more of the total annual production in the Invaded State (4.0).

Resilience management. Management strategies to sustain this plant community include setting proper stocking rates, monitoring utilization of key species, providing adequate time for plant recovery following grazing events or other disturbance events. If adequate native propagules remain in the plant community, long-term prescribed grazing, and prescribed burning, may reduce the amount of Kentucky bluegrass and other non-native cool-season grasses to facilitate a transition to the Native/Invaded State (2.0).

Another potential option to facilitate a transition to the Native/Invaded State (2.0), if deemed both ecologically and/or economically feasible. This would include, mechanical and/or chemical herbaceous weed control to reduce the non-native cool-season grasses, followed by a seeding of a native grass and forb species, and the implementation of long-term prescribed grazing.

Community 4.1

Kentucky Bluegrass-Wheatgrass-Smooth Brome/Green Sagewort

Figure 19. Channery Loam - PCP 3.1

This plant community is dominated by Kentucky bluegrass and/or other non-native cool-season grasses. These species will make up 30 percent or more of the total annual production. This plant community developed under long-term no use and no fire, or with continuous early-season stocking, and/or excessive haying.

This plant community is made up of approximately 85 percent grasses and grass-like species, 10 percent forbs, and 5 percent shrubs. Dominant grasses include Kentucky bluegrass and smooth brome. Western wheatgrass, slender or bearded wheatgrass, and a minor amount of needlegrass and little bluestem. Forbs commonly found will include western yarrow, scurfpeas, and goldenrod. Shrubs include green sagewort and fringed sagewort.

| Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

•Invasion of non-native cool-season grasses.

•Continuous season-long stocking: long-term grazing at moderate to moderately heavy stocking levels, during the typical growing season (May through October), without change in season of use or adequate recovery periods following grazing events.

•Excessive haying includes annual mechanical harvesting of rangeland plant communities without adequate time for plant recovery. Leaving inadequate post-harvest stubble height for retention of photosynthetic leaf area, nor providing adequate insulation cover from extreme heat or cold will result in a decline in plant health and vigor and increased plant mortality. Desirable grasses and forbs for forage and wildlife cover will decrease, and other less desirable grasses and forbs species will increase.

•Extended periods of no use and no fire results in heavy litter buildup which favors non-native cool-season grasses such as Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and other non-native species, and the reduction of native warm-season grasses.

Constraints to recovery. Disturbance regime results in the transition from plant communities dominated by native tall and mid- warm-season and cool-season grass to plant communities with up to 15 percent non-native cool-season grasses. Because of the adaptability and persistence of these non-native grass species, a recovery to the Reference State (1.0) is highly unlikely.

Transition T1B

State 1 to 3

•Heavy, continuous season-long stocking: long-term grazing at moderately heavy to heavy stocking levels, during the typical growing season (May through October), without change in season of use or adequate recovery periods following grazing events.

•Heavy, continuous stocking: repeated year-long grazing at moderately heavy to heavy stocking levels, without change in season of use or adequate recovery periods following grazing events.

•Heavy disturbance: Soil and site stability is compromised from one, or a combination of excessive grazing or defoliation, heavy livestock or vehicle traffic, wildfire, or drought.

•Shift in hydrologic function with reduced infiltration and increased runoff.

Constraints to recovery. Disturbance regime results in the transition from plant communities dominated by native tall and mid- warm-season and cool-season grass to plant communities dominated by short warm-season grasses, sedges, and clubmoss. Because of the persistence of these species and a shift in the functional structural groups, a recovery to the Reference State (1.0) is highly unlikely.

Transition T2B

State 2 to 3

•Heavy, continuous season-long stocking: long-term grazing at moderately heavy to heavy stocking levels, during the typical growing season (May through October), without change in season of use or adequate recovery periods following grazing events.

•Heavy, continuous stocking: repeated year-long grazing at moderately heavy to heavy stocking levels, without change in season of use or adequate recovery periods following grazing events.

•Heavy disturbance: Soil and site stability is compromised from one, or a combination of excessive grazing or defoliation, heavy livestock or vehicle traffic, wildfire, or drought.

•Shift in hydrologic function with reduced infiltration and increased runoff.

Constraints to recovery. Disturbance regime results in the transition from plant communities dominated by native tall and mid- warm-season and cool-season grass to plant communities dominated by short warm-season grasses, sedges, and clubmoss. Because of the persistence of these species and a shift in the, a recovery to the Native/Invaded State (2.0) is highly unlikely.

Transition T2A

State 2 to 4

•Long-term no use resulting in heavy litter buildup which favors non-native cool-season grasses such as Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and other non-native species, and the reduction of native warm-season grasses.

•Long-term no fire resulting in heavy litter buildup which favors non-native cool-season grasses such as Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and other non-native species, and the reduction of native warm-season grasses.

•Continuous early-season stocking including, repeated moderate to moderately heavy stocking levels, during the spring, early cool-season growing season (April through early June), without change in season of use or adequate recovery periods following grazing events.

•Excessive haying includes annual mechanical harvesting of rangeland plant communities without adequate time for plant recovery. Leaving inadequate post-harvest stubble height for retention of photosynthetic leaf area, nor providing adequate insulation cover from extreme heat or cold will result in a decline in plant health and vigor and increased plant mortality. Desirable grasses and forbs for forage and wildlife cover will decrease, and other less desirable plants will increase.

Constraints to recovery. Disturbance regime results in the transition from plant communities dominated by native tall and mid-statured warm- and cool-season grass, and non-native cool-season grasses that make up 15 percent or less of the plant community, to plant communities dominated by non-native cool-season grasses with native grasses being sub-dominant. Because of the persistence of non-native cool-season grasses, a recovery to the Native/Invaded State (2.0) is uncertain and may not be feasible.

Context dependence. Transition T2A is most likely going to occur from Plant Community 2.2.

Preliminary studies indicate this threshold may exist when Kentucky bluegrass exceeds 30 percent of the plant community, and native grasses represent less than 40 percent of the plant community composition. Plant communities dominated by Kentucky bluegrass have significantly less cover and diversity of native grasses and forb species. (Toledo, D. et al., 2014).

Transition T4A

State 4 to 2

•Early season prescribed burning followed by

•Long-term prescribed grazing including proper stocking rates, change in season of use, and adequate time for plant recovery following grazing events.

•These mechanisms, in combination, may shift the Invaded State (4.0) to the Native/Invaded State (2.0).

•Chemical and/or mechanical herbaceous weed control treatment, followed by seeding of native grass and forb species, and long-term prescribed grazing may be an option in some areas where channers are deeper in the soil profile. This could accelerate the reestablishment of structural functional groups similar to those in State 2.0, however, the resulting plant community may not achieve management objectives.

Constraints to recovery. Plant communities dominated by non-native cool-season grasses can be very resilient, and difficult to restore to a native dominated plant community. Preliminary studies would indicate this threshold occurs when Kentucky bluegrass exceeds 30 percent of the plant community, and native grasses represent less than 40 percent of the plant community (Toledo, D. et al., 2014). Because of the persistence of these species, a transition to the Native/Invaded State (2.0) may not be ecologically or economically feasible.

| Prescribed Burning |

|

| Prescribed Grazing |

|