Ecological dynamics

Unlike many terrestrial ecological sites, calcareous fens do not have a single, uniform plant community. Instead, they are a wetland complex typically comprised of different structural parts each with its own plant community or vegetation zone. Calcareous fens develop under very localized and uncommon hydrogeologic conditions where there are upwellings or lateral flows of mineral rich groundwater. On a glacial landscape, these rare hydrogeologic conditions are generally limited to three topographic locations: hillsides, lake/pond shorelines, and mounds on glacial outwash channels (Amon et al. 2002). These groundwater discharge sites support wetland plants whose root materials do not decompose because they are constantly suspended in cold, anoxic water. Peat deposits typically range from a few feet thick to over 10 feet thick representing thousands of years of accumulation (Malterer et al. 1988, Miner and Ketterling 2003, Yu et al. 2003).

Groundwater minerals consist primarily of calcium and other carbonates which are held in suspension until the water is discharged at the surface whereby these carbonates precipitate out of solution and form layers or deposits of marl (calcium rich mud or mudstone) and tufa (porous, crunchy rock of calcium carbonate). A typical fen complex consists of a small, circular or linear discharge zone often with a floating mat of vegetation. Below the discharge zone are often marl flats or slopes with relatively short, sparse vegetation interrupted by small pools of standing water. This transitions into a border zone or zones of wetland vegetation typically with a sharp or gradual transition from organic substrates to the mineral soils of more common, surrounding wetland or upland vegetation.

Discharge zone vegetation (often a floating mat) is relatively species poor and often dominated by coarse sedges and cattails, e.g. water sedge (Carex aquatilis), and broadleaf cattail (Typha latifolia), whereas the marl flat zone is typically very species rich and dominated by shorter, finer leaved graminoids, e.g. common threesquare (Schoenoplectus pungens), needle beaksedge (Rhynchospora capillacea), prairie sedge (Carex prairea), spiked muhly (Muhlenbergia glomerata), and marsh arrowgrass (Triglochin palustris). Marl flats also have an abundance of calcium loving and distinctive forbs, e.g. grass of Parnassus (Parnassia glauca), Ontario lobelia (Lobelia kalmii), lesser fringed gentian (Gentianopsis virgata), and northern bog aster (Symphyotrichum boreale). A floating-leaved aquatic plant – the lesser bladderwort (Utricularia minor) is frequently found in the tiny pools of water that occur throughout the marl flat zone, as is stonewart (Chara spp.) which, although it looks like a submerged aquatic vascular plant, is actually a multicelluar algae.

Below or outside of the marl flat may be border zones of wetland vegetation. These may vary from wet meadow types dominated by fine-stemmed grasses and sedges, e.g. bluejoint (Calamagrostis canadensis), or prairie cordgrass (Spartina pectinata); to deep marsh vegetation of cattails and bulrushes, or the water may converge into a stream channel along the downslope edge of the marl flat with riparian vegetation including shrubs.

In a study of Midwestern fens across 11 states, including South Dakota, Amon, et al. (2002) concluded that calcareous fens could best be distinguished from other wetland types by 4 characteristics: 1) they are dependent upon mineral rich groundwater discharge which moves through and saturates the root zone for most of the year; 2) unlike ponded wetlands, they do not experience flooding or long term inundation; 3) they develop organic soils, not from sphagnum mosses, but from fibrous roots and brown mosses, and develop carbonate deposits like marl and tufa; 4) they have botanically diverse plant communities dominated by non-emergent graminoids.

In one respect, calcareous fens are extremely stable, undisturbed environments. Only a continuously saturated, anoxic environment could allow the accumulation of peat deposits of 3 to 10 feet thick typical of many calcareous fens. Given the vagarity of the climate on the Great Plains including long term droughts, it is even more remarkable that such permanent and stable saturated conditions have persisted even on such a small scale as these fens. By the same token, these calcareous fens are embedded in a landscape where bison were abundant and prairie fires were frequent. Because of the soft, saturated peaty substrates and floating mats of vegetation fens are somewhat dangerous to large animals who may break through and become bogged down and eventually die in these fens. It seems likely that given alternative water holes, bison and elk would have avoided these boggy traps. Likewise, while prairie fires would have burned across the surface, the perpetually saturated nature of a fen precludes the damage or consumption of the peaty substrates. The fens that did dry up, would have been consumed by fire.

Most calcareous fens are small in size, rarely more than a few acres, which makes them especially vulnerable to hydrologic alteration, ground or surface water pollution, excessive trampling by livestock, invasion by exotic plant species, and easily damaged by herbicide drift or direct application of herbicides. While many calcareous fens discharge water that ultimately ends up in natural streams or ponds (which provide readily accessible water for livestock), some fens have dispersed flows into wetlands. Many such fens have been altered by ditching, damming or excavating for stock ponds. Ditching drains the water away from the root zone making those substrates unsuitable for wetland plants. Without constant saturation, the peat and organic soil begins to oxidize and decompose.

The hydrology of calcareous fens is complicated and difficult to quantify (Thompson et al. 1992, Almendinger and Leete 1998). Clearly these fens depend upon a reliable quantity and quality of groundwater discharge. Ditching alters the hydrology at the fen itself, but the hydrology can also be altered at the recharge end of the aquifer. Gravel mines can remove substantial portions of a near surface aquifer that feeds a fen or alter the recharge zone of such an aquifer. Large irrigation, municipal, or industrial wells can remove enough water from an aquifer to interrupt, if not totally dry up a fen. A relevant example comes from a proposed expansion the Lincoln-Pipestone Rural Water System in southwestern Minnesota. The original proposal called for increased pumping from the “Burr Well Field,” a series of wells located on an aquifer called the “Burr Unit of the Prairie Coteau Aquifer.” This Burr Unit was later mapped out to be an aquifer that, in aerial extent, measured more than 6 miles long and 4 miles wide, with a water-bearing sand and gravel lens that varied from 50 to 95 feet thick, underlain by 159 feet of clay and overlain by 50 to 100 feet of glacial till (Plank et al. 1998). At least six calcareous fen complexes were documented in the vicinity of this Burr Unit. By monitoring the hydraulic pressure at four of these fens while pumping from the aquifer, it was established that at least three of these fens were hydrologically connected to the Burr Unit and were negatively affected by substantial pumping from this Burr Unit aquifer (Plank et al. 1998).

Likewise, the water chemistry of fens is complicated and has not been entirely explained. For example, what causes the plants of the marl flat zone to be rather short and sparse? One theory is that the high calcium content causes phosphorus to precipitate out of solution into chemical forms that are not available to plants, thereby resulting in a nutrient poor condition that limits the growth of taller, more robust vegetation (Amon, et al. 2002). While these nutrient relationships remain mostly untested, it seems likely that the contamination of aquifers that supply water to calcareous fens could significantly alter the native flora and fauna of these habitats. Ground water recharge areas that are located in cropland or urban areas would seem especially vulnerable to increased levels of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus.

Like grassland ecological sites, calcareous fens support a diverse plant community that includes increaser and decreaser species based upon their palatability to livestock. Unfortunately, livestock preference of many fen plant species have not been determined.

It is clear that intensive livestock use can alter the surface hydrology of calcareous fen when cattle trample narrow ditches through the shallower peat mats as they trail through the fen. This has the effect of ditching and presumably lowers the water table in at least those portions of the fen so affected.

State 1

Reference State

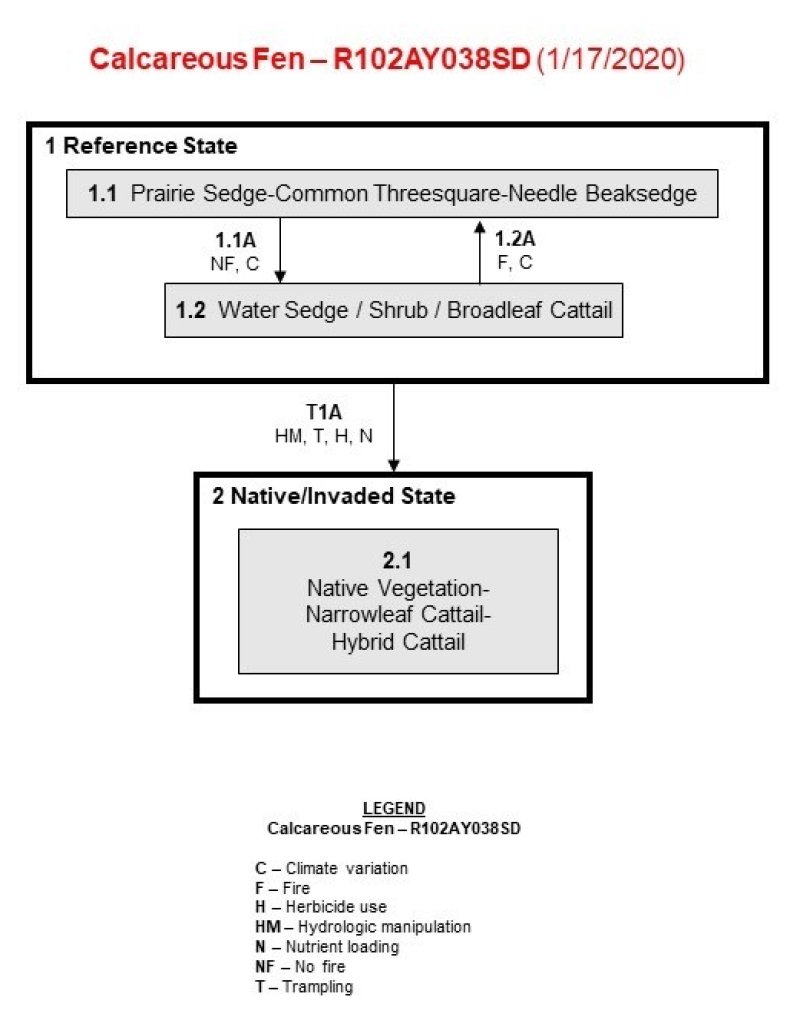

This state represents what is believed to show the natural range of variability that dominates the dynamics of the ecological state prior to European settlement. This site, in the Reference State (State 1), is a complex community with different vegetation zones. The marl flat zones are dominated by prairie sedge, common threesquare, and needle beaksedge. Below or outside of the marl flat may be border zones of wetland vegetation. These may vary from wet meadow types dominated by fine-stemmed grasses and sedges, e.g. bluejoint, or prairie cordgrass; to deep marsh vegetation of cattails and bulrushes, or the water may converge into a stream channel along the downslope edge of the marl flat with riparian vegetation including shrubs. The discharge zone is typically dominated by water sedge and broadleaf cattail.

Climatic variation, disturbance, and fire are drivers between community phases, while herbivory plays a very minor role as these areas are typically avoided by large ungulates. Invasion of non-native cattails may occur if the hydrology of the site is manipulated through ditching, draining, or excavating, nutrient loading, herbicide use, and/or trampling by livestock. Invasion may also occur due to changes in water pH. This will result in a transition to the Native/Invaded State (State 2).

Dominant plant species

-

sageleaf willow (Salix candida), shrub

-

redosier dogwood (Cornus sericea), shrub

-

meadow willow (Salix petiolaris), shrub

-

prairie sedge (Carex prairea), grass

-

common threesquare (Schoenoplectus pungens), grass

-

needle beaksedge (Rhynchospora capillacea), grass

-

spiked muhly (Muhlenbergia glomerata), grass

-

marsh arrowgrass (Triglochin palustris), grass

-

water sedge (Carex aquatilis), grass

-

broadleaf cattail (Typha latifolia), grass

-

grass of Parnassus (Parnassia), other herbaceous

-

Ontario lobelia (Lobelia kalmii), other herbaceous

-

lesser fringed gentian (Gentianopsis virgata), other herbaceous

-

northern bog aster (Symphyotrichum boreale), other herbaceous

Community 1.1

Prairie Sedge-Common Threesquare-Needle Beaksedge (Marl flat zone)

This area of the fen complex is dominated by marls (calcium rich mud or mudstone) and tufa (porous, crunchy rock of calcium carbonate). The zone is typically very species rich and dominated shorter, finer leaved graminoids such as prairie sedge, common threesquare, and needle beaksedge. Other graminoids that could occur on this site include spiked muhly and marsh arrowgrass. This vegetation zone also has an abundance of calcium-loving, distinctive forbs such as grass of Parnassus, Ontario lobelia, lesser fringed gentian, and northern bog aster. This zone is also interrupted by tiny pools of water that support floating aquatic plants such as lesser bladderwort and muticelluar algae like stonewart.

Community 1.2

Water Sedge/Shrub/Broadleaf cattail (Discharge zone)

The Discharge zone vegetation is often found on a floating mat of organic material. This zone is often species poor and dominated by coarse sedges and cattails such as water sedge (Carex aquatilis), and broadleaf cattail (Typha latifolia). Shrub vegetation may include sageleaf willow (Salix candida), redosier dogwood (Cornus sericea), and meadow willow (Salix petiolaris).

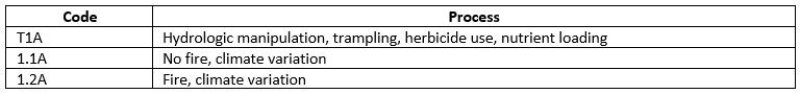

Pathway 1.1A

Community 1.1 to 1.2

Climatic variation, no fire and/or lack of disturbance will shift this community to the 1.2 Water Sedge/Shrub/Broadleaf Cattail (Discharge zone) plant community phase.

Pathway 1.2A

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Climatic variation, fire and/or disturbance will shift this community to the 1.2 Prairie Sedge-Common Threesquare-Needle Beaksedge (Marl flat zone) within the Reference State (State 1).

State 2

Invaded State

The Native/Invaded State is characterized by a shift from native species to inclusion of invasive cattail species such as narrowleaf (Typha angustifolia) and hybrid cattail (Typha x glauca) due to hydrologic manipulation from ditching, draining, or excavating, nutrient loading, herbicide use, and/or trampling by livestock. The various forms of manipulation result in a lowered water table, which allows peat and organic soils to decompose in absence of saturation. This altered site provides an environment for non-natives and exotics to invade.

Dominant plant species

-

narrowleaf cattail (Typha angustifolia), grass

-

hybrid cattail (Typha ×glauca), grass

-

common reed (Phragmites australis), grass

-

redtop (Agrostis gigantea), grass

-

prairie sedge (Carex prairea), grass

-

common threesquare (Schoenoplectus pungens), grass

-

needle beaksedge (Rhynchospora capillacea), grass

-

spiked muhly (Muhlenbergia glomerata), grass

-

marsh arrowgrass (Triglochin palustris), grass

-

purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), other herbaceous

-

grass of Parnassus (Parnassia), other herbaceous

-

Ontario lobelia (Lobelia kalmii), other herbaceous

-

lesser fringed gentian (Gentianopsis virgata), other herbaceous

-

northern bog aster (Symphyotrichum boreale), other herbaceous

Community 2.1

Native Vegetation-Narrowleaf Cattail-Hybrid Cattail

This community phase is still a complex of native and invasive vegetation. Native vegetation will still include species such broadleaf cattail, prairie sedge, and water sedge, but also will include invasive species such as narrowleaf cattail, hybrid cattail, common reed, purple loosestrife, redtop (Agrostis gigantea), and others.

Transition T1A

State 1 to 2

Hydrological manipulation such as ditching, draining, or excavating, nutrient loading from the watershed, herbicide use and/or trampling by livestock may all lead to this shift in plant community. Invasion of nonnative cattails, common reed (Phragmites australis), and invasive forbs such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) leads to a Native/Invaded State (State 2).