Natural Resources

Conservation Service

Ecological site R106XY074NE

Clayey Upland

Last updated: 2/04/2019

Accessed: 11/24/2024

General information

Approved. An approved ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model, enough information to identify the ecological site, and full documentation for all ecosystem states contained in the state and transition model.

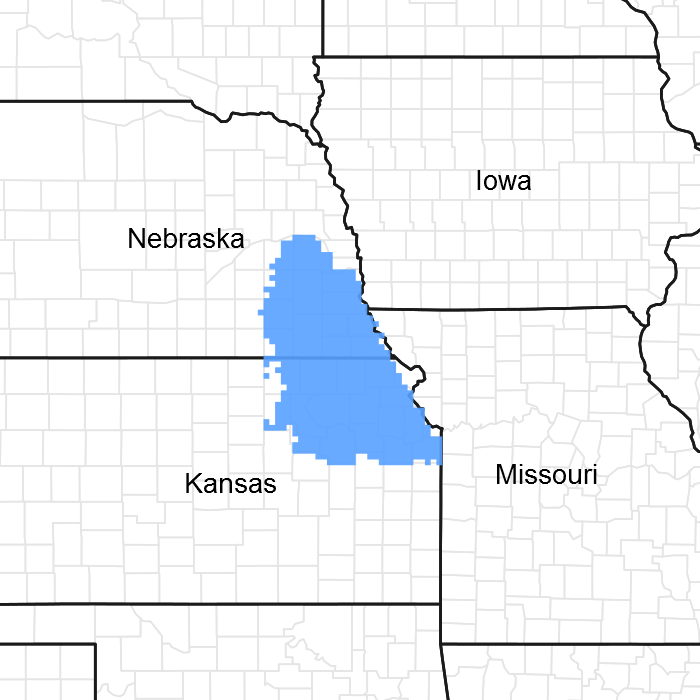

Figure 1. Mapped extent

Areas shown in blue indicate the maximum mapped extent of this ecological site. Other ecological sites likely occur within the highlighted areas. It is also possible for this ecological site to occur outside of highlighted areas if detailed soil survey has not been completed or recently updated.

MLRA notes

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 106X–Nebraska and Kansas Loess-Drift Hills

Revision Notes: This ESD has been revised to meet the latest requirements for both the provisional and the approved status.

MLRA Notes:

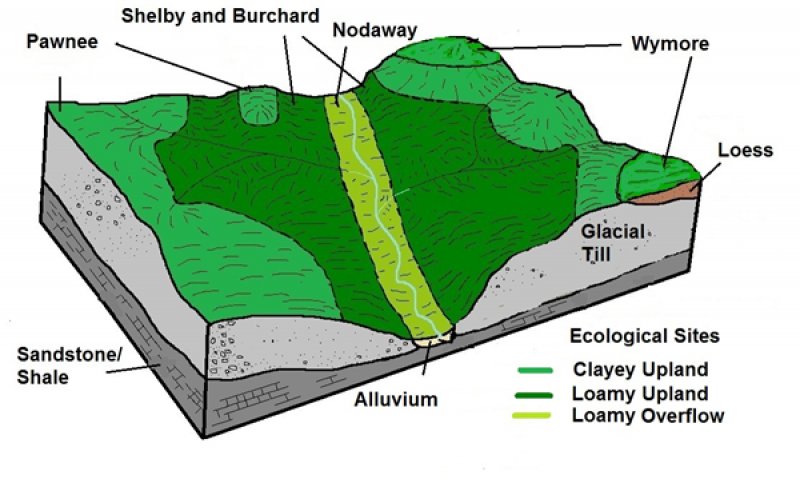

Loess covers the surface of almost all of the uplands in this MLRA. Glacial drift underlies the loess. Alluvial clay, silt, sand, and gravel are deposited in all of the stream and river valleys. The alluvial deposits can be extensive in the major river valleys. Paleozoic sandstone, shale, and limestone units are exposed in a few road cuts and in the walls of valleys along the major streams on the east side of the area, near the bluffs along the Missouri River. Limestone and shale (clay) quarries are in this MLRA.

Classification relationships

Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 106 Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) and Land Resource Unit (LRU) (USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2006)

Clayey range site for NE NRCS Vegetation Zone 4

Clay Upland range site for KS portion of MLRA 106

NE Natural Heritage Program/NE Game & Parks Commission: "Upland Tallgrass Prairie"

General information for MLRA 106:

*Fenneman (1916) Physiographic Regions* Division – Interior Plains

Province – Central Lowland

Section – Dissected Till Plains

*USFS (2007) Ecoregions*

Domain – Humid Temperate

Division – Prairie

Province – Prairie Parkland (Temperate)

Section – Central Dissected Till Plains (251C)

*EPA Ecoregions (Omernik 1997)*

I – Great Plains (9)

II – Temperate Prairies (9.2)

III – Western Corn Belt Plains (9.2.3)

IV – Loess and Glacial Drift Hills (47i)

*Associated Counties*

Nebraska: Butler, Cass, Gage, Jefferson, Johnson, Lancaster, Nemaha, Otoe, Pawnee, Richardson, Saline, Saunders, Seward

Kansas: Atchison, Brown, Doniphan, Douglas, Franklin, Jackson, Jefferson, Johnson, Leavenworth, Marshall, Nemaha, Osage, Pottawatomie, Shawnee, Wabaunsee, Washington, Wyandotte

Ecological site concept

This site occurs on higher, stable landscape positions that produce run-off from soils with more than 35 percent clay content in the surface horizons. As described in the eco-site key for MLRA 106, the Clayey Upland Ecological Site can occur on non-effervescent soils ranging from silt-loams to clay-loams with depths of more than 20 inches.

Associated sites

| R106XY070NE |

Loamy Terrace Receiving positions on lower landscape positions, typically on terraces |

|---|---|

| R106XY075NE |

Loamy Upland Similar landscape positions and often intermixed; best distinguished by less than 35 percent clay content |

| R106XY077NE |

Shallow Limy Typically found on steeper areas and/or narrow summits |

Similar sites

| R106XY075NE |

Loamy Upland Similar composition, higher production, average clay content is less than 35 percent in A horizons with lower AWC |

|---|---|

| R106XY070NE |

Loamy Terrace Similar plant composition but higher production |

| R106XY077NE |

Shallow Limy Higher mid-grass contribution, significantly lower production, limestone/shale within 20” |

Table 1. Dominant plant species

| Tree |

Not specified |

|---|---|

| Shrub |

Not specified |

| Herbaceous |

(1) Andropogon gerardii |

Physiographic features

The site occurs on nearly level to steep slopes, foot slopes, and uplands. See the Ecological Dynamics Section for the discussion on aspect influence on the site.

While the percent slope of the soil series associated with this site ranges from 0 to 25 percent, the vast majority of Clayey uplands are situated on slopes of 15 percent or less.

Figure 2. Clayey Upland Block Diagram

Table 2. Representative physiographic features

| Landforms |

(1)

Hill

(2) Plain |

|---|---|

| Flooding frequency | None |

| Ponding frequency | None |

| Elevation | 228 – 516 m |

| Slope | 0 – 25% |

| Ponding depth | 0 cm |

| Water table depth | 91 cm |

| Aspect | N, S |

Climatic features

Like most Great Plains landscapes, the climate in this MLRA is under the sway of the continental effect. This creates a regime of extremes, with summer highs often in the triple digits, and winter lows plunging well below zero. Blizzards can occur anytime between early fall and late spring, often dropping the temperature more than 50 degrees in just a few hours. These events can pile up several feet of snow, often driven by winds in excess of 50 miles an hour. The resulting huge snow drifts can cause serious hardship for livestock, wildlife, and humans. Winters can be open, with bare ground for most of the season, or closed, with up to several feet of snow persisting until March. Most winters have a number of warm days, interspersed with dropping temperatures, usually associated with approaching cold fronts. Spring brings violent thunderstorms, hail, and high winds. Tornadoes occur frequently.

About three-fourths of the precipitation falls as high-intensity, convective thunderstorms from late in spring through early in autumn.

The average annual precipitation gradient trends higher from northwest (28”) to southeast (40”), and the average annual temperature gradient trends higher from north (50°F) to south (55°F).

Daily winds range from an average of 14 miles per hour during the spring to 11 miles per hour during the late summer. Occasional strong storms may bring brief periods of high winds with gusts to more than 80 miles per hour.

Growth of native cool-season plants begins in early April and continues to about mid-June. Native warm-season plants begin growth in early June, and continue to early August. Green-up of cool-season plants may occur in September and October.

Table 3. Representative climatic features

| Frost-free period (average) | 164 days |

|---|---|

| Freeze-free period (average) | 184 days |

| Precipitation total (average) | 914 mm |

Figure 3. Monthly precipitation range

Figure 4. Monthly average minimum and maximum temperature

Figure 5. Annual precipitation pattern

Figure 6. Annual average temperature pattern

Climate stations used

-

(1) BONNER SPRINGS [USC00140957], Bonner Springs, KS

-

(2) HOLTON [USC00143759], Holton, KS

-

(3) LAWRENCE [USC00144559], Lawrence, KS

-

(4) OSKALOOSA 4 NE [USC00146100], Mc Louth, KS

-

(5) ASHLAND NO 2 [USC00250375], Ashland, NE

-

(6) PAWNEE CITY [USC00256570], Pawnee City, NE

-

(7) TOPEKA MUNI AP [USW00013996], Topeka, KS

-

(8) LINCOLN UNIV PWR PLT [USW00014971], Lincoln, NE

-

(9) CLINTON LAKE [USC00141612], Lawrence, KS

-

(10) VIRGINIA [USC00258875], Virginia, NE

-

(11) FALLS CITY BRENNER FLD [USW00094957], Falls City, NE

-

(12) MARYSVILLE [USC00145063], Marysville, KS

-

(13) BEATRICE 1N [USC00250622], Beatrice, NE

-

(14) CRETE [USC00252020], Crete, NE

-

(15) MEAD 6S [USC00255362], Ithaca, NE

-

(16) RAYMOND 2NE [USC00257055], Raymond, NE

-

(17) TABLE ROCK 4 N [USC00258410], Table Rock, NE

-

(18) LINCOLN MUNI AP [USW00014939], Lincoln, NE

-

(19) CENTRALIA [USC00141408], Centralia, KS

-

(20) HIAWATHA 9 ESE [USC00143634], Robinson, KS

-

(21) HORTON [USC00143810], Horton, KS

-

(22) PERRY LAKE [USC00146333], Perry, KS

-

(23) AUBURN 5 ESE [USC00250435], Auburn, NE

-

(24) SYRACUSE [USC00258395], Syracuse, NE

-

(25) TECUMSEH 1S [USC00258465], Tecumseh, NE

-

(26) WAHOO [USC00258905], Wahoo, NE

-

(27) WEEPING WATER [USC00259090], Weeping Water, NE

Influencing water features

This site may occur on stream terraces but is not affected by flooding. A perched water table is present in most of these soils in the spring. The site is not considered hydric.

Soil features

This site consists of moderately deep to very deep, clayey soils. Surface textures range from silt loam to clay loam. The subsoil is silty clay or clay and has greater than 45 percent clay. These soils typically are not hydric. Depth to carbonates ranges from 24 to greater than 80 inches.

The Reference Plant Community should exhibit slight to no evidence of rills, wind scoured areas, or pedestaled plants. Water flow paths, if any, are broken, irregular in appearance or discontinuous with numerous debris dams or vegetative barriers. The soil surface is stable and intact.

Major soil series correlated to this ecological site include: Pawnee, Wymore, Wamego, Grundy and Mayberry.

Figure 7. Pawnee profile

Table 4. Representative soil features

| Surface texture |

(1) Silty clay loam (2) Clay loam |

|---|---|

| Family particle size |

(1) Clayey |

| Drainage class | Somewhat poorly drained to well drained |

| Permeability class | Very slow to slow |

| Soil depth | 0 – 203 cm |

| Surface fragment cover <=3" | 0 – 10% |

| Surface fragment cover >3" | 0% |

| Available water capacity (0-101.6cm) |

10.16 – 17.78 cm |

| Calcium carbonate equivalent (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 15% |

| Electrical conductivity (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 2 mmhos/cm |

| Sodium adsorption ratio (0-101.6cm) |

0 – 4 |

| Soil reaction (1:1 water) (0-101.6cm) |

5.6 – 8.4 |

| Subsurface fragment volume <=3" (Depth not specified) |

0 – 15% |

| Subsurface fragment volume >3" (Depth not specified) |

0% |

Ecological dynamics

The Reference Community for this site is tallgrass prairie occurring on higher, stable landscape positions that generate runoff. Gentler slopes comprise well-developed soils with favorable precipitation capture and retention, while steeper areas exhibit higher run-off with carbonates remaining near the surface. Under normal weather and soil conditions, sunlight and energy capture is a primary factor limiting plant growth, making this site ideal to support warm-season tallgrass communities. The vegetation on this site is locally impacted by topography, and the steepness and aspect of the slope interact with the other ecological processes to further influence vegetative dynamics. The north and east facing slopes are usually cooler and wetter, which results in increased vegetation production, but favors invasion by trees and shrubs as well. This often makes these slopes more resistant to restoration of the native grasslands by fire. They may require use of specific ignition techniques when conducting a prescribed burn to ensure mortality of invading trees.

This site developed with fire as an integral part of the ecological processes. Historically, a given area burned approximately every 3-4 years. Distribution was random, but timing generally corresponded to the summer season when convective thunderstorms are most likely to occur. However, it is also believed that pre-European inhabitants may have used fire as a management tool for attracting herds of large migratory herbivores (bison, elk, and/or deer) as well as for warfare. The role of fire over the past 100 years has been relatively insignificant due to the human control of wildfires and general lack of acceptance of prescribed fire as a management tool. In this region where natural precipitation is capable of supporting eastern deciduous forest, much of this site is vulnerable to encroachment by woody species.

The degree of herbivory has significant impacts on ecological processes such as nutrient cycling and sunlight capture. Historically, these sites were highly attractive to herds of large migratory herbivores, and grazing patterns and impacts were a primary influence. Secondary influences of herbivory by species such as insects, rodents, and root-feeding organisms impacted the vegetation historically, and continue to this day (Helzer, 2010). The management of herbivory by humans through grazing of domestic livestock and manipulation of wildlife populations has been a major modern influence on the ecological dynamics (USDA/SCS, 1977).

Fire historically played a critical role in maintaining the heterogeneity of this system by removing decadent plant material and creating highly palatable new growth. Large herbivores were attracted to the burned areas, and created "grazing lawns". These areas were repeatedly grazed until a new burned area reduced grazing pressure until the area was left undisturbed. The heterogeneity of vegetative diversity and structure of the landscape created by the numerous patches in various states of vegetative recovery was essential to maintaining a diverse wildlife population. These conditions created the array of seasonal niches necessary for the various wildlife species to thrive. Grassland birds are one suite of species whose habitat requirements are particularly dependent on the mosaic of vegetative structure created by the pyric herbivory/ungulate interactions.

Patch burn grazing is an emerging management concept that attempts to emulate this historic system.

Whereas herds of native ungulates could move freely across the landscape in response to changing conditions, livestock use is constrained in space and often repeated over time, producing a more homogeneous landscape. Grasses with highly elevated growing points (e.g. big bluestem, Indiangrass, gamagrass) and preferred shrubs are the most susceptible to growing-season defoliation and typically the first to decrease under improper grazing. Noxious weeds such as leafy spurge, sericea lespedeza, and musk and Canada thistles may take advantage of reduced native cover and vigor; however, the cool-season grasses smooth brome, and tall fescue pose the greatest invasion threat. Smooth brome is generally the dominant invader in Nebraska while tall fescue is more common in Kansas.

The favorable growing conditions and topography that historically made this one of the largest contributors to the “true prairie” habitat type in this MLRA have also made it one of the most extensively cropped today. The Reference Plant Community has been determined by study of rangeland relic areas, areas protected from abusive disturbance, seasonal use pastures, areas under long-term rotational grazing practices, and historical accounts.

The State and Transition Model (STM) is depicted below, and is made up of a Reference State, a Native/Invaded State, a Sod-busted State and an Invaded Woody State. Each state represents the crossing of a major ecological threshold due to alteration of the functional dynamic properties of the ecosystem. The main properties observed to determine this change are the soil and vegetative communities, and the hydrological cycle.

Each state may have one or more vegetative communities that fluctuate in species composition and abundance within the normal parameters of the state. Within each state, communities may degrade or recover in response to natural and man caused disturbances such as variation in the degree and timing of herbivory, presence or absence of fire, and climatic and local fluctuations in the precipitation regime.

Interpretations are primarily based on the Reference State, and have been determined by study of rangeland relic areas, areas protected from excessive disturbance, and areas under long-term rotational grazing regimes. Trends in plant community dynamics have been interpreted from heavily grazed to lightly grazed areas, seasonal use pastures, and historical accounts. Plant communities, states, transitional pathways, and thresholds have been determined through similar studies and experience.

Growth of native cool season plants begins about April 1, and continues to about June 15. Native warm season plants begin growth about May 15, and continue to about August 15. Green up of cool season plants may occur in September and October if adequate moisture is available.

The species distribution and abundance on this site are also influenced by the degree of inclination and aspect of the local topography. Northern and eastern slopes are typically cooler and wetter, generally producing more biomass than the drier and warmer exposures. Severe inclines receive less grazing pressure than the more moderate slopes.

The following is a diagram that illustrates the common plant communities that can occur on the site and the transition pathways between communities.

State and transition model

More interactive model formats are also available.

View Interactive Models

Click on state and transition labels to scroll to the respective text

State 1 submodel, plant communities

Communities 1, 5 and 2 (additional pathways)

State 2 submodel, plant communities

State 3 submodel, plant communities

State 4 submodel, plant communities

State 1

Reference State

This state comprises the communities within the range of natural variability under historic conditions and disturbance regimes. Patterns created by wildlife use and fire supported a mosaic of communities across the landscape. Warm-season tallgrasses are dominant, with subdominant contributions from mid and cool-season grasses, forbs, and shrubs. Eastern gamagrass is naturally absent in the northern half of the MLRA, but becomes increasingly common southward. Conversely, cool-season grasses, such as porcupine grass and Canada wildrye, are more prominent northward. High perennial grass cover allows for increased soil moisture retention, vegetative production, and overall soil quality. Fire and bison herbivory were the dominant disturbance regimes that historically maintained the tallgrass dominance with a diverse forb component. Furthermore, bison grazing was closely linked to fire patterns as the animals preferred grazing burned areas offering highly palatable and nutritious regrowth. Thus, historic plant communities were subject to occasional burning and grazing, with substantial rest/recovery periods as the fuel load rebuilt to eventually start this process again. Fires also served to suppress woody species and to maintain an open herbaceous stand. The degree to which current conditions represent this state largely depends upon how closely contemporary management has mimicked these past disturbance effects.

Community 1.1

Tallgrass Prairie

Figure 8. Gage County, Nebraska

The reference plant community is 75-90 percent grasses and grass-like plants, 5-10 percent forbs, and 0-10 percent shrubs, based upon total annual air-dry weight production. Big bluestem, Indiangrass, little bluestem, porcupine grass, sideoats grama, and switchgrass are the dominant species making up 70 percent or more of the total annual production. Blue grama, prairie junegrass, Scribner’s rosette grass (panicum or panic grass), tall dropseed and various sedges, shrubs, and forbs are also important plants to the site (Kaul 2006, Steinauer 2010, USDA/NRCS 2012). This plant community is very stable but there is annual variability of expression of the dominant plant species based on current climate and local disturbances. Late spring fires will stimulate warm-season plants while suppressing cool-season grasses and forbs. This plant community is very stable with very little water runoff. The total annual production ranges from 2800 to 4900 pounds of air dry vegetation per acre per year. The production curve may vary, with increasingly later growth as you move north in the MLRA.

Figure 9. Annual production by plant type (representative values) or group (midpoint values)

Table 5. Annual production by plant type

| Plant type | Low (kg/hectare) |

Representative value (kg/hectare) |

High (kg/hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grass/Grasslike | 2928 | 3812 | 4792 |

| Forb | 185 | 319 | 504 |

| Shrub/Vine | 39 | 128 | 241 |

| Tree | – | – | – |

| Total | 3152 | 4259 | 5537 |

Figure 10. Plant community growth curve (percent production by month). NE1068, MLRA 106 Warm-season. *Warm-season dominant.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

| 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 18 | 30 | 22 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Community 1.2

Degraded Tallgrass Prairie

Figure 11. SE Nebraska-Degraded Community

This community marks a significant reduction in warm-season tallgrasses that have decreased due to continued excessive defoliation and/or prolonged drought. Warm-season midgrasses such as little bluestem and sideoats grama increase to fill the void left by declining tallgrass species. These species are not as productive as the species they replace, causing a decline in vegetative biomass and forage compared to the reference community. They are also less deeply rooted, and create less residue, contributing to reduced efficiencies in the nutrient, mineral, and hydrologic cycles, all factors impacting overall soil health. Total average annual production ranges from 2,950 to 3,800 pounds of air-dry lbs/ac with an average of 3,400 lbs/ac.

Community 1.3

At-Risk Native Grass Community

Figure 12. At-Risk Community- SE Nebraska

In this plant community, the more palatable tall warm-season grasses have been reduced to remnant populations by continued defoliation during their critical growth periods. Grazing-evasive warm-season and cool-season grasses increase significantly. Bluegrass encroachment also occurs on flatter slopes. Soil health is affected by reduced efficiency in the nutrient, mineral, and hydrologic cycles as a result of decreases in plant litter and rooting depths.

Community 1.4

Excessive Litter Community

The Excessive Litter Community Phase describes the response of the community to the removal of the natural disturbances of herbivory and fire. As the undisturbed duff layer deepens, infiltration of the precipitation is interrupted and evaporation increases significantly, simulating drought-like conditions.

Community 1.5

Ephemeral Forb Community

This community describes the flush of forbs that occurs in response to a major disturbance, or combination of disturbances. Growing season wildfire followed by hail, extreme prolonged drought, or extreme defoliation by herbivores are all examples of these disturbances. The native warm-season grasses re-establish dominance with-in a few years of the event.

Pathway CP 1.1-1.2

Community 1.1 to 1.2

A shift from the Tallgrass Prairie to the Degraded Tallgrass community occurs with heavy grazing and inadequate recovery periods during the growing season.

Pathway CP 1.1-1.4

Community 1.1 to 1.4

Lack of natural disturbance, i.e. herbivory and fire.

Pathway CP 1.1-1.5

Community 1.1 to 1.5

A high-impact disturbance event or combination of events causing excessive defoliation of the vegetation, i.e. a growing season wildfire followed by a significant hailstorm, prolonged intensive grazing event, or long-term drought, etc.

Pathway CP 1.2-1.1

Community 1.2 to 1.1

Managed grazing/haying regime to allow growing season rest of desirable tall-grass species; return to normal precipitation regime.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

Pathway CP 1.2-1.3

Community 1.2 to 1.3

Timing, frequency, and degree of herbivory/haying that negatively affects desirable tall-grass species; long-term drought.

Pathway CP 1.2-1.4

Community 1.2 to 1.4

Lack of natural disturbance, i.e. herbivory and fire.

Pathway CP 1.2-1.5

Community 1.2 to 1.5

A high-impact disturbance event or combination of events causing excessive defoliation of the vegetation, i.e. a growing season wildfire followed by a significant hailstorm, prolonged intensive grazing event, or long-term drought, etc.

Pathway CP 1.3-1.2

Community 1.3 to 1.2

Reversing the downward trend to the previous community can be achieved with prescribed grazing early and late in the growing season to reduce undesirable cool season grasses. Targeting the peak growth period of cool season grasses with high intensity grazing events followed by rest will allow the tall native warm season grasses to rejuvenate. Appropriately timed prescribed fire will accelerate this process.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Access Control | |

| Prescribed Grazing |

Pathway CP 1.3-1.4

Community 1.3 to 1.4

Interruption of the natural disturbances of herbivory and fire will result in conversion from this community to the Excessive Litter Community.

Pathway CP 1.3-1.5

Community 1.3 to 1.5

A high-impact disturbance event, or combination of events causing excessive defoliation of the vegetation, i.e. a growing season wildfire followed by a significant hailstorm, or a prolonged intensive grazing event, or long-term drought, etc.

Pathway CP 1.4-1.1

Community 1.4 to 1.1

Re-introduction of the natural processes of herbivory and fire will allow the vegetation to return to the previous community.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

Pathway CP 1.4-1.2

Community 1.4 to 1.2

Re-introduction of the natural processes of herbivory and fire will allow the vegetation to return to the previous community.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

Pathway CP 1.4-1.5

Community 1.4 to 1.5

A high-impact disturbance event, or combination of events causing excessive defoliation of the vegetation, i.e. a growing season wildfire followed by a significant hailstorm, or a prolonged intensive grazing event, or long-term drought, etc.

Pathway CP 1.5-1.1

Community 1.5 to 1.1

Restoration occurs naturally once the disturbance event has subsided. Allowing growing season rest will accelerate the recovery.

Pathway CP 1.5-1.2

Community 1.5 to 1.2

Restoration occurs naturally once the disturbance event has subsided. Allowing growing season rest will accelerate the recovery.

Pathway CP 1.5-1.3

Community 1.5 to 1.3

Restoration occurs naturally once the disturbance event has subsided. Allowing growing season rest will accelerate the recovery.

State 2

Native/Invaded Grass State

This state exhibits a co-dominance of both native and introduced species. Very few native tall warm-season grasses such as big bluestem and Indiangrass remain. The plant community consists of the more grazing tolerant native species and a significant component of introduced grasses. Forb diversity is limited to less palatable species such as ironweed and western ragweed. Impaired energy capture and altered hydrologic function are reflected in reduced vegetative productivity, shallower rooting depth and degraded soil quality.

Community 2.1

Native Evaders/Invasives

Figure 13. Brome invaded Tallgrass Prairie- SE Nebraska

This plant community represents a shift from the Reference State across a community threshold. With continued undermanaged grazing, little bluestem and cool-season introduced grasses increase. Smooth brome is the dominant invader in the northern half of the MLRA while tall fescue is common in the south. Kentucky bluegrass may be subdominant throughout. Continuous heavy grazing pressure will convert this plant community to a sodbound condition. Forb richness and diversity will decrease as well. Total annual production ranges from 1,800 and 2,900 pounds of air-dry herbage per acre per year, and produce about 2,300 pounds per acre in average years.

Community 2.2

Smooth brome- Tall fescue

Figure 14. Tall fescue, Eastern Nebraska.

Figure 15. Smooth Brome- SE Nebraska

This community is predominately smooth brome or tall fescue and may have a Kentucky bluegrass sub-component. Native warm-season grass remnants may or may not still be present. Smooth brome primarily occurs throughout the northern half of the MLRA, while tall fescue is common in the south. Vegetative production from smooth brome and tall fescue dominated communities can be highly variable depending on the species composition and external inputs such as fertilizer and weed control. In a normal year, biomass produced can range from 2,500 to 3,000 lbs./acre, with an average of 2,750 on rangelands with a dominant cool season grass component of 75 percent or more.

Pathway CP 2.1-2.2

Community 2.1 to 2.2

Persisting stressors on desirable species allow for further expansion and dominance of brome and/or tall fescue. Site structure and function largely resemble a seeded pasture monoculture, although scattered natives may still be found. Introduced grass seeding, continuous warm season grazing, mid to late summer haying, and untimely and/or excessive fertilization will increase cool-season invaders.

Pathway CP 2.2-2.1

Community 2.2 to 2.1

Establishing a grazing regime that focuses pressure during the cool season grasses' active growth period while providing rest during the warm season growing season will promote a shift back to community phase 2.1. Prescribed fires used in conjunction with a cool-season grazing program will accelerate the process. In the presence of a viable native seedbank, non-selective herbicides applied in the early spring and late fall when invaders are actively growing can be beneficial. Established stands of the cool season invaders may require complete renovation through chemical treatment followed by re-seeding of the native vegetation. Once the warm-season community is re-established, ongoing prescribed grazing and fire management with adequate rest and recovery during the summer months is critical.

Conservation practices

| Prescribed Burning | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Grazing |

State 3

Sod-Busted State

Extensive areas of this ecological site were plowed and converted to crop production by early European settlers and their subsequent generations. In addition to permanently altering the the existing vegetative community, repeated tillage negatively impacted soil properties. Reductions in organic matter, mineral levels, soil structure, oxygen levels, and water-holding capacity along with increased runoff and erosion as well as shifts in the populations of soil-dwelling organisms were common on these sites. The extent of these changes depended upon the duration of cropping as well as crops grown and other management practices. At this present time there are no restoration arrows from this state to another state.

Community 3.1

Natural Reclamation

This plant community consists of annual and perennial weeds and less desirable grasses. These sites have been farmed and abandoned without being reseeded. Soil organic matter/carbon reserves are reduced, soil structure is changed, and a plow-pan or compacted layer can be formed which decreases water infiltration. Residual synthetic chemicals may remain from farming operations. In early successional stages, this community is not stable. Erosion is a concern. Total annual production during an average year varies significantly depending on the succession stage of the plant community and any management applied to the system.

Community 3.2

Reseeded Grass

This plant community does not contain native remnants, and varies considerably depending on the seed mixture, the degree of soil erosion, the age of the stand, nitrogen fertilizer use, and past grazing management. Prescribed grazing with adequate recovery periods will be needed to maintain productivity and desirable species. Native range and seeded grasslands are ecologically different, and should be managed separately. Factors such as functional group, species, stand density, and improved varieties all impact the production level and palatability of the seedings. Species diversity is often limited, and when grazed in conjunction with native rangelands, uneven forage utilization may occur. Total annual production during an average year varies significantly depending on precipitation, management, and grass species seeded. Single species stands of Big bluestem, Indiangrass or switchgrass or well managed cool-season grasses/legume plantings with improved varieties yield 3,000-4,000 lbs./acre/year.

State 4

Invaded Woody State

This state is invaded by woody species, primarily eastern redcedar, but also honey locust or other invasive deciduous trees. These woody species are present due to lack of fire and/or brush management measures.

Community 4.1

Eastern Redcedar/Deciduous

Figure 16. Eastern redcedar invaded grassland- SE Nebraska

If eastern redcedar is the dominant tree, the canopy cover is at least 30 percent. Honey locust and smooth sumac encroachment may also be occurring when brush management and prescribed or wild fires are absent over an extended period. The grassland has converted to woodland resulting in a closed canopy that dramatically reduces the resources available for herbaceous production by intercepting rainfall and sunlight. Total annual production during an average year varies significantly, depending upon the production level prior to encroachment and the percentage of tree canopy cover.

Transition T1-2

State 1 to 2

Repeated defoliation of preferred native tall and mid-grass warm-season species during periods of active growth reduces individual plant vigor and competitiveness. This facilitates an increase by the more grazing- evasive native warm-season grasses, and cool- season species. As big bluestem, little bluestem, and Indiangrass decrease, cool- season invaders such as smooth brome and/or tall fescue colonize and expand to such a degree that restoration to the reference state through grazing management alone is unlikely. The native forb and shrub component is also affected by the season and degree of livestock pressure. In response to repeated defoliation, this community will shift to less palatable, more grazing tolerant species that includes non-native invaders. Repeated growing season haying causes a similar species composition shift in the reference plant community.

Transition T1-3

State 1 to 3

This transition occurs when the native grassland is sodbusted and planted to crops or seeded to non-native forage species. Return to the representative plant community is judged to be highly unlikely if not impossible at this stage due to irreversible alterations of the soil properties.

Transition T1-4

State 1 to 4

All herbaceous communities are vulnerable to woody dominance in the absence of fire or mechanical brush management. Bur oak, eastern red cedar, coralberry, osage orange, roughleaf dogwood, and honey locust are some of the first species to increase. Although these plants are native to North America, they were not historically a significant part of this reference community. If allowed to continue with little or no disturbance, eastern red cedar, oaks and elm trees will eventually dominate. If ERC is present, the transition is generally thought to occur when its' canopy cover reaches approximately 30 percent. As the overstory closes, various processes serve to increase woody dominance. Woody foliage shades the understory and intercepts rainfall increasing evaporative loss. Litterfall acts similarly and further reduces effective precipitation while also creating a less uniform resource distribution with nutrients concentrated under individual trees. At some critical point, the understory becomes incapable of carrying a fire of the intensity needed to kill the woody species, and the disturbance response is now dictated by the overstory. Mature oak forest is largely invulnerable to stand replacement fire, while established eastern redcedar stands can only burn as crown fires.

Transition T2-3

State 2 to 3

This transition occurs when the native grassland is sodbusted and planted to crops or seeded to non-native forage species. Return to the representative plant community is judged to be highly unlikely if not impossible at this stage due to irreversible alterations of the soil properties.

Transition T2-4

State 2 to 4

All herbaceous communities are vulnerable to woody dominance in the absence of fire or mechanical brush management. Bur oak, eastern red cedar, coralberry, osage orange, roughleaf dogwood, and honey locust are some of the first species to increase. Although these plants are native to North America, they were not historically a significant part of this reference community. If allowed to continue with little or no disturbance, eastern red cedar, oaks and elm trees will eventually dominate. If ERC is present, the transition is generally thought to occur when its' canopy cover reaches approximately 30 percent. As the overstory closes, various processes serve to increase woody dominance. Woody foliage shades the understory and intercepts rainfall increasing evaporative loss. Litterfall acts similarly and further reduces effective precipitation while also creating a less uniform resource distribution with nutrients concentrated under individual trees. At some critical point, the understory becomes incapable of carrying a fire of the intensity needed to kill the woody species, and the disturbance response is now dictated by the overstory. Mature oak forest is largely invulnerable to stand replacement fire, while established ERC stands can only burn as crown fires.

Transition T3-4

State 3 to 4

All herbaceous communities are vulnerable to woody dominance in the absence of fire or mechanical brush management. Bur oak, eastern red cedar, coralberry, osage orange, roughleaf dogwood, and honey locust are some of the first species to increase. Although these plants are native to North America, they were not historically a significant part of this reference community. If allowed to continue with little or no disturbance, eastern red cedar, oaks and elm trees will eventually dominate. If ERC is present, the transition is generally thought to occur when its' canopy cover reaches approximately 30 percent. As the overstory closes, various processes serve to increase woody dominance. Woody foliage shades the understory and intercepts rainfall increasing evaporative loss. Litterfall acts similarly and further reduces effective precipitation while also creating a less uniform resource distribution with nutrients concentrated under individual trees. At some critical point, the understory becomes incapable of carrying a fire of the intensity needed to kill the woody species, and the disturbance response is now dictated by the overstory. Mature oak forest is largely invulnerable to stand replacement fire, while established ERC stands can only burn as crown fires.

Restoration pathway R4-1,2,3

State 4 to 1

Restoration to an herbaceous condition can be achieved with brush management for woody plant removal, but whether the outcome includes native and/or introduced herbs will depend heavily on understory composition and seedbank. Stands of mature deciduous trees generally are invulnerable to fire, and grassland restoration will require mechanical means. Mature redcedar may be removed either mechanically or with fire; however, prescribed burns should consider site stability as well as logistical, legal, and safety constraints. Furthermore, sprouting brush such as honey locust or elm must be chemically treated after mechanical removal. If the site is stable and has a robust seedbank, this community could quickly return to a grassland state with proper follow-up management. Ongoing brush management such as hand cutting, chemical spot treatments, or periodic prescribed burning is required.

Conservation practices

| Brush Management | |

|---|---|

| Prescribed Burning |

Additional community tables

Table 6. Community 1.1 plant community composition

| Group | Common name | Symbol | Scientific name | Annual production (kg/hectare) | Foliar cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grass/Grasslike

|

||||||

| 1 | Tall Warm-Season | 1491–1917 | ||||

| big bluestem | ANGE | Andropogon gerardii | 1065–1704 | – | ||

| Indiangrass | SONU2 | Sorghastrum nutans | 213–639 | – | ||

| eastern gamagrass | TRDA3 | Tripsacum dactyloides | 0–426 | – | ||

| switchgrass | PAVI2 | Panicum virgatum | 213–426 | – | ||

| 2 | Mid Warm Season Grasses | 809–2130 | ||||

| little bluestem | SCSC | Schizachyrium scoparium | 639–1278 | – | ||

| composite dropseed | SPCO16 | Sporobolus compositus | 85–426 | – | ||

| sideoats grama | BOCU | Bouteloua curtipendula | 85–213 | – | ||

| purple lovegrass | ERSP | Eragrostis spectabilis | 0–213 | – | ||

| 3 | Short Warm Season Grasses | 85–213 | ||||

| blue grama | BOGR2 | Bouteloua gracilis | 0–213 | – | ||

| hairy grama | BOHI2 | Bouteloua hirsuta | 0–85 | – | ||

| 4 | Cool Season Grasses | 85–213 | ||||

| porcupinegrass | HESP11 | Hesperostipa spartea | 85–426 | – | ||

| Canada wildrye | ELCA4 | Elymus canadensis | 0–128 | – | ||

| prairie Junegrass | KOMA | Koeleria macrantha | 0–85 | – | ||

| western wheatgrass | PASM | Pascopyrum smithii | 0–85 | – | ||

| Scribner's rosette grass | DIOLS | Dichanthelium oligosanthes var. scribnerianum | 0–85 | – | ||

| fall rosette grass | DIWI5 | Dichanthelium wilcoxianum | 0–85 | – | ||

| 5 | Grasslike | 43–213 | ||||

| sedge | CAREX | Carex | 43–213 | – | ||

|

Forb

|

||||||

| 6 | Forbs | 185–426 | ||||

| Missouri goldenrod | SOMI2 | Solidago missouriensis | 0–128 | – | ||

| white heath aster | SYER | Symphyotrichum ericoides | 0–95 | – | ||

| false boneset | BREU | Brickellia eupatorioides | 0–95 | – | ||

| purple prairie clover | DAPU5 | Dalea purpurea | 0–95 | – | ||

| Maximilian sunflower | HEMA2 | Helianthus maximiliani | 0–95 | – | ||

| stiff sunflower | HEPA19 | Helianthus pauciflorus | 0–95 | – | ||

| western yarrow | ACMIO | Achillea millefolium var. occidentalis | 0–85 | – | ||

| Cuman ragweed | AMPS | Ambrosia psilostachya | 0–85 | – | ||

| field pussytoes | ANNE | Antennaria neglecta | 0–85 | – | ||

| white sagebrush | ARLU | Artemisia ludoviciana | 0–85 | – | ||

| groundplum milkvetch | ASCR2 | Astragalus crassicarpus | 0–85 | – | ||

| butterfly milkweed | ASTU | Asclepias tuberosa | 0–85 | – | ||

| compassplant | SILA3 | Silphium laciniatum | 0–85 | – | ||

| hoary verbena | VEST | Verbena stricta | 0–85 | – | ||

| stiff goldenrod | OLRI | Oligoneuron rigidum | 0–85 | – | ||

| prairie groundsel | PAPL12 | Packera plattensis | 0–48 | – | ||

| silverleaf Indian breadroot | PEAR6 | Pediomelum argophyllum | 0–48 | – | ||

| cobaea beardtongue | PECO4 | Penstemon cobaea | 0–48 | – | ||

| large Indian breadroot | PEES | Pediomelum esculentum | 0–48 | – | ||

| slimflower scurfpea | PSTE5 | Psoralidium tenuiflorum | 0–48 | – | ||

| upright prairie coneflower | RACO3 | Ratibida columnifera | 0–48 | – | ||

| fringeleaf wild petunia | RUHU | Ruellia humilis | 0–48 | – | ||

| azure blue sage | SAAZ | Salvia azurea | 0–48 | – | ||

| prairie blue-eyed grass | SICA9 | Sisyrinchium campestre | 0–48 | – | ||

| white prairie clover | DACA7 | Dalea candida | 0–48 | – | ||

| aromatic aster | SYOB | Symphyotrichum oblongifolium | 0–48 | – | ||

| longbract spiderwort | TRBR | Tradescantia bracteata | 0–48 | – | ||

| whorled milkweed | ASVE | Asclepias verticillata | 0–48 | – | ||

| longbract wild indigo | BABR2 | Baptisia bracteata | 0–48 | – | ||

| roundhead lespedeza | LECA8 | Lespedeza capitata | 0–48 | – | ||

| tall blazing star | LIAS | Liatris aspera | 0–48 | – | ||

| dotted blazing star | LIPU | Liatris punctata | 0–48 | – | ||

| Nuttall's sensitive-briar | MINU6 | Mimosa nuttallii | 0–48 | – | ||

| evening primrose | OENOT | Oenothera | 0–48 | – | ||

| Carolina larkspur | DECAV2 | Delphinium carolinianum ssp. virescens | 0–48 | – | ||

| Illinois ticktrefoil | DEIL2 | Desmodium illinoense | 0–48 | – | ||

| blacksamson echinacea | ECAN2 | Echinacea angustifolia | 0–48 | – | ||

| button eryngo | ERYU | Eryngium yuccifolium | 0–48 | – | ||

|

Shrub/Vine

|

||||||

| 7 | Shrubs | 43–213 | ||||

| coralberry | SYOR | Symphoricarpos orbiculatus | 0–95 | – | ||

| leadplant | AMCA6 | Amorpha canescens | 0–85 | – | ||

| Jersey tea | CEHE | Ceanothus herbaceus | 0–48 | – | ||

| smooth sumac | RHGL | Rhus glabra | 0–48 | – | ||

| prairie rose | ROAR3 | Rosa arkansana | 0–48 | – | ||

| western snowberry | SYOC | Symphoricarpos occidentalis | 0–48 | – | ||

Interpretations

Animal community

Livestock - Grazing Interpretations:

Grazing by domestic livestock is one of the major income-producing industries in the area. Rangeland in this area may provide yearlong forage for cattle, sheep, or horses. During the dormant period, the protein levels of the forage may be lower than the minimum needed to meet livestock (primarily cattle and sheep) requirements.

Wildlife Habitat Interpretations:

When the plant community structure of this tallgrass prairie site is maintained, this site provides excellent nesting areas for quail, pheasant, and prairie chickens, especially when it is associated with adjacent booming grounds. The variety of forbs, grasses, and insects on this site makes it a preferred feeding area for deer and birds. Numerous songbirds utilize this site for nesting and other activities.

Changes to the structure and species composition of the plant community in ways that reduce the availability of the food and cover that attracts these species to this site. However, some animal species favor alternative community phases/states. For additional habitat components beyond the scope of this ESD, refer to species specific habitat appraisal guides.

In the absence of fire and grazing, excess litter buildup can occur on this site hindering the movement of young birds, especially quail and prairie chickens. Additionally, decreased forb abundance/diversity will result in an accompanying decrease in insects, a critical food source for young birds.

Numerous rodents and small animals utilize this site by taking advantage of the taller growing plants to visually shield them from predators.

Hydrological functions

Hydrology Functions:

Water is the principal factor limiting forage production on this site. Shrub invasion, particularly by eastern red cedar, greatly exacerbates this issue. Control of invasive shrubs by Rx fire and mechanical means are important tools in maintaining the site as a grassland.

Soils in this Ecological site are generally in hydrolgic group D. Infiltration rate is moderately slow to slow. Runoff potential for this site varies from low to very high depending on soil hydrologic group, slope and ground cover.

For the representative plant community, rills and gullies should not typically be present. Water flow patterns should be barely distinguishable if at all present. Pedestals are only slightly present in association with bunchgrasses such as little bluestem. Litter typically falls in place, and signs of movement are not common. Chemical and physical crusts are rare to non-existent. Cryptogamic crusts are present but only cover 1-2 percent of the soil surface. Overall this site has the appearance of being stable and productive.

Recreational uses

This site provides hunting for upland game species along with hiking, photography, bird watching, and other opportunities. The wide varieties of plants which bloom from spring until fall have an aesthetic value that appeals to visitors.

Wildflowers are abundant on this site. The most visible wildflowers change from year to year due to the variability among the growing seasons. Because of this variety of wildflowers and grasses, many people tour and collect plant materials from this site for dried floral arrangements.

Wood products

Although several tree species invade this site, they usually do not reach sufficient size to produce wood products except for firewood.

Other products

The deep, productive nature of the soils associated with this site make it attractive for a variety of other land uses. When in large blocks on flatter slopes, they are preferred cropland soils. Introduced pasture plants do well on these soils.

Other information

Site Development and Testing Plan

Future work needed to validate the information in this Ecological Site Description is needed to develop this ESD to the Correlated level. This will include field activities to collect high intensity sampling, soil correlations, and analysis of that data. Field reviews of the project plan should be done by soil scientists and vegetation specialists. A final field review, peer review, quality control, and quality assurance reviews of the ESD will be needed to produce the final document.

A project plan needs to be developed for this site.

Supporting information

Inventory data references

Information presented here has been derived from RANGE-417 archives, Rangeland NRI, and other inventory data. Field observations from range-trained personnel were also used. In addition to the multitude of NRCS field office employees and private landowners that helped with site visits and local knowledge, those involved in developing this site include:

Nebraska NRCS

Nadine Bishop, State Rangeland Management Specialist

Dan Shurtliff, Asst State Soil Scientist

Sam Cowan, Soil Conservationist

Kansas NRCS

David Kraft, State Rangeland Management Specialist

Tim Miller, Area Rangeland Management Specialist

Dwayne Rice, Area Rangeland Management Specialist

MLRA Office 5

Stu McFarland, Ecological Site Inventory Specialist, QC

Mark Moseley, Ecological Site Inventory Specialist, QA

Chris Tecklenburg, Ecological Site Inventory Specialist, QC

John Warner, Soil Data Quality Specialist

Bruce Evans, 5-LIN MSSO Project Leader

National Soil Survey Center

Mike Kucera, National Agronomist, Soil Quality & Ecosystems

Steve Peaslee, GIS Specialist, Soil Survey Interpretations

Nebraska Game & Parks Commission

Gerry Steinauer, Botanist

Nebraska Forest Service

Steve Karloff, District Forester

Dennis Adams, Program Leader

University of Nebraska – Lincoln Extension

Bruce Anderson, Forage Specialist

These are the positions each individual held when the project was initiated.

Type locality

| Location 1: Douglas County, KS | |

|---|---|

| Township/Range/Section | T11S R20E S33 |

| General legal description | Rockefeller Prairie, University of Kansas Field Station. |

Other references

Fenneman, Nevin M. 1916. Physiographic Subdivision of the United States. Annals of the

Association of American Geographers.

Helzer, Chris. 2010. The Ecology and Management of Prairies in the Central U.S. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press/The Nature Conservancy.

Kaul, Robert B., David Sutherland, and Steven Rolfsmeier. 2006. The Flora of Nebraska. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska – Lincoln (Conservation and Survey Division, School of Natural Resources.)

Multiple authors. 2010. Rangelands: Ecological Sites (Special Issue) pp 2-64. Wheat Ridge, CO: Society for Range Management.

NOA/UNL – High Plains Regional Climate Center. Historical Data Summaries:

http://www.hprcc.unl.edu/data/historical/

Steinauer, Gerry and Steve Rolfsmeier. 2010. Terrestrial Ecological Systems and Natural Communities of Nebraska. Lincoln, NE: Nebraska Natural Heritage Program and Nebraska Game and Parks Commission.

USDA/ARS/SWRC. 2013. Dynamic Rangeland Hydrology and Erosion Model Tool (DRHEM), Version 2.0. http://apps.tucson.ars.ag.gov/drhem/

USDA/USFS. 2007. Ecological Subregions: Sections and Subsections for the Conterminous United

States. Washington, DC: USDA - Forest Service.

USDA/SCS. 1977. Rangeland Resources of Nebraska. Lincoln, NE: Society for Range Management. USDA/NRCS. 2011. ESD User Guide. Fort Worth, TX: Central National Technology Support

Center.

USDA/NRCS. 2003. National Range and Pasture Handbook. Fort Worth, TX: Grazing Lands

Technical Institute.

USDA/NRCS. 2012a. Field Office Technical Guide (Nebraska, Natural Resources Information, Statewide Soil and Site Information, Rangeland Interpretations, Nebraska Range Site Descriptions – Vegetative Zone 4), U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Nebraska Ecological Sciences.

USDA/NRCS. 2012b. Field Office Technical Guide (Kansas, Natural Resources Information, Ecological Site Descriptions, Range Sites), U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Nebraska Ecological Sciences.

USDA/NRCS 2006. Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. U.S. Department of Agriculture Handbook 296.

Original Site Description Approval:

Author Date Approval Date

DLarsen 11/28/2007 DLarsen 11/28/2007

Contributors

Initiated By Stu Mcfarland Revised And Completed By Doug Whisenhunt

Approval

David Kraft, 2/04/2019

Rangeland health reference sheet

Interpreting Indicators of Rangeland Health is a qualitative assessment protocol used to determine ecosystem condition based on benchmark characteristics described in the Reference Sheet. A suite of 17 (or more) indicators are typically considered in an assessment. The ecological site(s) representative of an assessment location must be known prior to applying the protocol and must be verified based on soils and climate. Current plant community cannot be used to identify the ecological site.

| Author(s)/participant(s) |

Joseph A. May, State Rangeland Management Specialist Doug Whisenhunt Ecological Site Specialist |

|---|---|

| Contact for lead author |

NRCS 1202 S cottonwood North Platte NE 69101 doug.whisenhunt@ne.usda.gov |

| Date | 01/02/2015 |

| Approved by | Nadine L Bishop |

| Approval date | |

| Composition (Indicators 10 and 12) based on | Annual Production |

Indicators

-

Number and extent of rills:

Few, if any. No active headcutting and sides are covered with vegetation. -

Presence of water flow patterns:

Little, if any, soil deposition or erosion. Water generally flows evenly over the entire landscape. -

Number and height of erosional pedestals or terracettes:

No pedestaled plant or terracettes. -

Bare ground from Ecological Site Description or other studies (rock, litter, lichen, moss, plant canopy are not bare ground):

95% or more of the ground is covered by plant canopy, litter, and stones. When prescribed burning is practiced there is little litter the first half of the growing season. -

Number of gullies and erosion associated with gullies:

Few, if any. No active headcutting and sides are covered with vegetation -

Extent of wind scoured, blowouts and/or depositional areas:

Wind has not created, or enlarged, bare areas or denuded vegetation. -

Amount of litter movement (describe size and distance expected to travel):

Plant litter is distributed evenly throughout the site. -

Soil surface (top few mm) resistance to erosion (stability values are averages - most sites will show a range of values):

Plant canopy intercepts the majority of raindrops. There is no evidence of pedestaled plants or terracettes. A soil fragment will not "melt" or lose its structure when immersed in water for 30 seconds. -

Soil surface structure and SOM content (include type of structure and A-horizon color and thickness):

The topsoil layer has not been plowed or eroded. -

Effect of community phase composition (relative proportion of different functional groups) and spatial distribution on infiltration and runoff:

No negative effect due to plant composition or distribution. No rill formation or plant pedestalling has occurred. Any alteration to infiltration or runoff is due to cultural practices. -

Presence and thickness of compaction layer (usually none; describe soil profile features which may be mistaken for compaction on this site):

NO compacted soil layers due to cultural practices. -

Functional/Structural Groups (list in order of descending dominance by above-ground annual-production or live foliar cover using symbols: >>, >, = to indicate much greater than, greater than, and equal to):

Dominant:

Warm season (tall bunchgrasses)- Big bluestem, Indiangrass, Switchgrass.Sub-dominant:

Warm sesason (mid-bunchgrasses) - Sideoats grama, Little bluestem.Other:

Minor (grasses) - Canada and Virginia wildrye, blue grama, Scribners rosette grass,

sedges.

Additional:

Minor (forbs) - Black sampson, compassplant, daisy fleabane, dotted gayfeather, heath aster, cudweed sagewort, scurfpea, spiderwort, ragweed, woolly plaintain.

Trace: Shrubs - lead plant, prairie rose.

Additional: Warm season bunch grasses comprise 40% to 100% of the plant composition.

-

Amount of plant mortality and decadence (include which functional groups are expected to show mortality or decadence):

The vast majority of plants are healthy and vigorous. -

Average percent litter cover (%) and depth ( in):

Plant litter is evenly distributed evenly throughout. There is no restriction to plant regeneration due to depth of litter. When prescribed burning is practiced there will be little litter the first half of the growing season.

-

Expected annual annual-production (this is TOTAL above-ground annual-production, not just forage annual-production):

2,800 - 6,000 pounds per acre. -

Potential invasive (including noxious) species (native and non-native). List species which BOTH characterize degraded states and have the potential to become a dominant or co-dominant species on the ecological site if their future establishment and growth is not actively controlled by management interventions. Species that become dominant for only one to several years (e.g., short-term response to drought or wildfire) are not invasive plants. Note that unlike other indicators, we are describing what is NOT expected in the reference state for the ecological site:

Annual broomweed, common sunflower, fall witchgrass, kochia, little barley, silver bluestem, tansy mustard, Japanese brome, wild lettuce, flannel mullein, woolly verbena, windmill grass. -

Perennial plant reproductive capability:

Desirable perennial plants are healthy. The vast majority of perennial plants have a healthy root system that produces many rhizomes.

Print Options

Sections

Font

Other

The Ecosystem Dynamics Interpretive Tool is an information system framework developed by the USDA-ARS Jornada Experimental Range, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and New Mexico State University.

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.