Ecological site group R023XY903NV

Ashy 10-14 PZ Lahontan Sagebrush

Last updated: 06/03/2024

Accessed: 03/14/2026

Ecological site group description

Key Characteristics

- Site does not pond or flood

- Landform other than dunes

- Surface soils are not clayey

- Sites are shrub or grass dominated

- [Criteria]MAP >10"

- Soil is moderately deep or deeper

- Site on other aspects or landforms

- Soil textures (PCS) ashy

- Sites are on backslopes of ash flow landforms

Provisional. A provisional ecological site description has undergone quality control and quality assurance review. It contains a working state and transition model and enough information to identify the ecological site.

Physiography

This group is on mountains and plateaus at elevations between 5,500 and 7,500 feet. Slopes are between 15 and 40 percent.

Climate

The climate is classified as Cold Semi-Arid in the Koppen Classification System.

The area receives between 10 and 14 inches of annual precipitation as snow in the winter and rain in spring and fall. Summers are generally dry.

The frost-free period is 70 to 90 days per year. The mean annual air temperature is 45 °F.

Soil features

The soils in this group are shallow to moderately deep and well drained. Surface soils are medium to moderately coarse textured. Subsurface soils are medium textured. There are very high amounts of vitric volcanic ash and glass throughout the soil profile which enhances the water holding capacity of these soils.

The soils in this group are generally moderately deep Mollisols, such as the Ashone and Ashdos series.

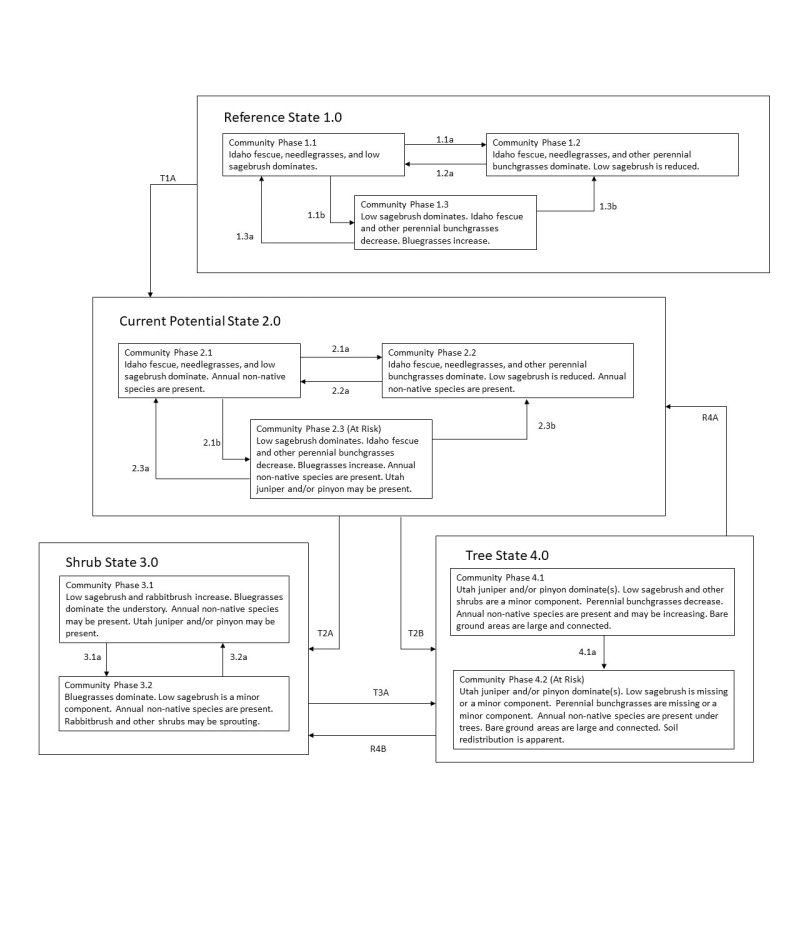

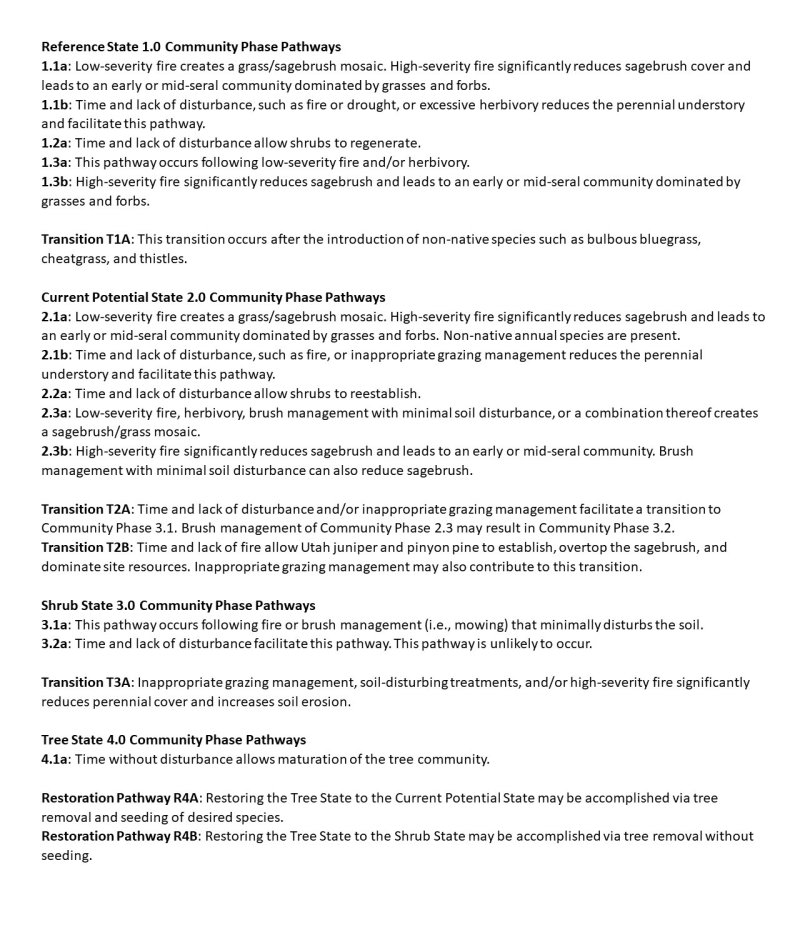

Vegetation dynamics

Ecological Dynamics and Disturbance Response:

An ecological site is the product of all the environmental factors responsible for its development. Each site has a set of key characteristics that influence its resilience to disturbance and resistance to invasives. According to Caudle et al. (2013), key characteristics include:

1. Climate factors such as precipitation and temperature.

2. Topographic characteristics such as aspect, slope, elevation, and landform.

3. Hydrologic processes such as infiltration and runoff.

4. Soil characteristics such as depth, texture, structure, and organic matter.

5. Plant communities and their functional groups and productivity.

6. Natural disturbance (fire, herbivory, etc.) regime.

Biotic factors that that influence resilience include site productivity, species composition and structure, and population regulation and regeneration (Chambers et al., 2013).

The ecological sites in this group are dominated by deep-rooted, cool-season, perennial bunchgrasses and long-lived shrubs (at least 50 years old) with high root to shoot ratios. The dominant shrubs usually root to the full depth of the winter-spring soil moisture recharge, which ranges from 1.0 to over 3.0 meters (Dobrowolski et al., 1990). However, community types with low sagebrush (Artemesia arbuscula) as the dominant shrub may only have available rooting depths of 71 to 81 centimeters (Jensen, 1990). These shrubs have a flexible generalized root system with development of both deep taproots and laterals near the surface (Comstock & Ehleringer, 1992). Periodic drought regularly influences sagebrush ecosystems, and drought duration and severity have increased throughout the 20th century in much of the Intermountain West. Major shifts away from historical precipitation patterns have the greatest potential to alter ecosystem function and productivity. Species composition and productivity can be altered by the timing of precipitation and water availability within the soil profile (Bates et al., 2006).

Low sagebrush is fairly drought tolerant but also tolerates periodic wetness during some portion of the growing season (Fosberg & Hironaka, 1964; Blackburn et al., 1968a, 1968b, 1969a, 1969b). It grows on soils that have a strongly structured B2t (argillic) horizon close to the soil surface (Winward, 1980; Fosberg & Hironaka, 1964; Zamora & Tueller, 1973). Low sagebrush is also susceptible to the sagebrush defoliator known as the Aroga moth (Aroga websteri). While the Aroga moth can partially or entirely kill individual plants or entire stands of big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) (Furniss & Barr, 1975), research is inconclusive of the damage sustained by low sagebrush populations.

Lahontan sagebrush was only recently identified as a unique species of sagebrush (Winward & McArthur, 1995). Lahontan sagebrush is a cross between low sagebrush and Wyoming sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. wyomingensis). It typically grows near the old shorelines of Lake Lahontan from the Pleistocene Epoch. This subspecies grows on soils similar to low sagebrush with shallow depths and low water holding capabilities (Winward & McArthur, 1995).

Utah juniper (Juniperus osteosperma) is a long-lived tree species with wide ecological amplitudes (Tausch et al., 1981; West et al., 1998; Weisberg & Ko, 2012). Maximum ages of pinyon and juniper exceed 1,000 years and stands with maximum age classes are only found on steep, rocky slopes with no evidence of fire (West et al., 1975).

Infilling by younger trees increases canopy cover, causing a decrease in understory perennial vegetation and an increase in bare ground. As juniper trees increase in density so does their litter. Phenolic compounds of juniper scales can have an inhibitory effect on grass growth (Jameson, 1970). Furthermore, infilling shifts stand level biomass from ground fuels to canopy fuels which has the potential to significantly impact fire behavior. The more tree-dominated the site becomes, the less likely it is to burn under moderate conditions, resulting in infrequent, high-intensity fires (Gruell, 1999; Miller et al., 2008). Additionally, as the understory vegetation declines in vigor and density with increased canopy cover, the seed and propagules of the understory plant community also decrease significantly. The increase in bare ground allows for the invasion of non-native annual species such as cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum). Following intense wildfire, the potential for conversion to annual exotics is a serious threat (Tausch, 1999; Miller et al., 2008).

Juniper growth depends mostly upon soil moisture stored from winter precipitation, mainly snow. Much of the summer precipitation is ineffective because it is lost either through runoff after summer convection storms or though evaporation and interception (Tueller & Clark, 1975). Juniper is highly resistant to drought, which is common in the Great Basin. Taproots of juniper have a relatively rapid rate of root elongation and are thus able to persist until precipitation conditions are more favorable (Emerson, 1932). At the southern end of this ecological site group’s extent, Utah Juniper may be the dominant species or may coexist and/or hybridize with western juniper (Juniperus occidentalis).

The Great Basin sagebrush communities have high spatial and temporal variability in precipitation both among years and within growing seasons (MacMahon, 1980). Nutrient availability is typically low but increases with elevation and closely follows moisture availability. The invasibility of plant communities is often linked to resource availability. Disturbance changes resource uptake and increases nutrient availability, often to the benefit of non-native species; native species are often damaged and their ability to use resources is depressed for a time, but resource pools may increase from lack of use and/or the decomposition of dead plant material following disturbance (Whisenant, 1999; Miller et al., 2013). The invasion of sagebrush communities by cheatgrass has been linked to disturbances (fire, abusive grazing) that result in fluctuations in resources (Beckstead & Augspurger, 2004; Chambers et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2011).

The ecological sites in this group have low to moderate resilience to disturbance and resistance to invasion. Resilience increases with elevation, northerly aspect, precipitation, and nutrient availability. Five possible stable states have been identified for this group.

Annual Invasive Grasses:

The species most likely to invade these sites are cheatgrass and medusahead (Taeniatherum). Both species are cool- season annual grasses that maintain an advantage over native plants in part because they are prolific seed producers, able to germinate in the autumn or spring, tolerant of grazing, and increase with frequent fire (Klemmedson & Smith, 1964; Miller et al., 1999). Medusahead and cheatgrass originated from Eurasia and both were first reported in North America in the late 1800s (Mack & Pyke, 1983; Furbush, 1953). Pellant and Hall (1994) found 3.3 million acres of public lands dominated by cheatgrass and suggested that another 76 million acres were susceptible to invasion by winter annuals including cheatgrass and medusahead. By 2003, medusahead occupied approximately 2.3 million acres in 17 western states (Rice, 2005). In the Intermountain West, the exponential increase in dominance by medusahead has largely been at the expense of cheatgrass (Harris, 1967; Hironaka, 1994). Medusahead matures 2 to 3 weeks later than cheatgrass (Harris, 1967). Recently, James et al. (2008) measured leaf biomass over the growing season and found that medusahead maintained vegetative growth later in the growing season than cheatgrass. Mangla et al. (2011) also found medusahead had a longer period of growth and more total biomass than cheatgrass and hypothesized this difference in relative growth rate may be due to the ability of medusahead to maintain water uptake as upper soils dry compared to co-occurring species, especially cheatgrass. Medusahead litter has a slow decomposition rate because of its high silica content, allowing it to accumulate over time and suppress competing vegetation (Bovey et al., 1961; Davies & Johnson, 2008). Harris (1967) reported medusahead roots have thicker cell walls compared to those of cheatgrass, allowing it to more effectively conduct water, even in very dry conditions.

Recent modeling and empirical work by Bradford and Lauenroth (2006) suggest that seasonal patterns of precipitation input and temperature are also key factors determining regional variation in the growth, seed production, and spread of invasive annual grasses. Collectively, the body of research suggests that the invasion and dominance of medusahead onto native grasslands and cheatgrass-infested grasslands will continue to increase in severity because conditions that favor native bunchgrasses or cheatgrass over medusahead are rare (Mangla et al., 2011). Medusahead replaces native vegetation and cheatgrass directly by competition and suppression; it replaces native vegetation indirectly by increasing fire frequency.

Methods to control medusahead and cheatgrass include herbicide, fire, grazing, and seeding of primarily non-native wheatgrasses. Mapping potential or current invasion vectors is a management method designed to increase the cost effectiveness of control methods. A study by Davies et al. (2013) found an increase in medusahead cover near roads. Cover was higher near animal trails than random transects, but the difference was less evident. This implies that vehicles and animals aid the spread of the weed; however, vehicles are the major vector of movement. Spraying with herbicide (Imazapic or Imazapic and glyphosate) and seeding with crested wheatgrass (Agropyron cristatum) and Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda) have been more successful at combating medusahead and cheatgrass than spraying alone (Sheley et al., 2012). Where native bunchgrasses are missing from the site, revegetation of medusahead- or cheatgrass-invaded rangelands has a higher likelihood of success when using introduced perennial bunchgrasses such as crested wheatgrass (Davies et al., 2015). Butler et al. (2011) tested four herbicides (Imazapic, Imazapic + glyphosate, rimsulfuron, and sulfometuron + Chlorsulfuron), using herbicide-only treatments, for suppression of cheatgrass, medusahead, and ventenata (Ventenata dubia) within residual stands of native bunchgrass. Additionally, they tested the same four herbicides followed by seeding of six bunchgrasses (native and non-native) with varying success. Herbicide-only treatments appeared to remove competition for established bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata) by providing 100 percent control of ventenata and medusahead and greater than 95 percent control of cheatgrass. However, caution in using these results is advised, as only one year of data was reported.

Prescribed fire has also been utilized in combination with the application of pre-emergent herbicide to control medusahead and cheatgrass (J. L. Vollmer & J. G. Vollmer, 2008). Mature medusahead or cheatgrass is very flammable and fire can be used to remove the thatch layer, consume standing vegetation, and even reduce seed levels. Furbush (1953) reported that timing a burn while the seeds were in the milk stage effectively reduced medusahead the following year. He further reported that adjacent unburned areas became a seed source for reinvasion the following year.

When considering the combination of pre-emergent herbicide and prescribed fire for invasive annual grass control, it is important to assess the tolerance of desirable brush species to the herbicide being applied. J. L. Vollmer and J. G. Vollmer (2008) tested the tolerance of mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus montanus), antelope bitterbrush (Purshia tridentata), and multiple sagebrush species to three rates of Imazapic and the same rates with methylated seed oil as a surfactant. They found a cheatgrass control program in an antelope bitterbrush community should not exceed Imazapic at 8 ounces per acre with or without surfactant. Sagebrush, regardless of species or rate of application, was not affected. However, many environmental variables were not reported in this study and managers should install test plots before broad scale herbicide application is initiated.

Fire Ecology:

To date, there are no specific studies on the fire response of Lahontan sagebrush. However, it likely behaves similarly to low sagebrush.

Low sagebrush is killed by fire and does not sprout (Tisdale & Hironaka, 1981). Fire risk is greatest following a wet, productive year when there is greater production of fine fuels (Beardall & Sylvester, 1976). Fire return intervals are not well understood because these ecosystems rarely coincide with fire-scarred conifers, but a wide range of 20 to well over 100 years has been estimated (Miller & Rose, 1995, 1999; Baker, 2006; Knick et al., 2005). Historically, fires were probably patchy due to the low productivity of these sites (Beardall & Sylvester, 1976; Ralphs & Busby, 1979; Wright et al., 1979; Smith & Busby, 1981). Fine fuel loads generally average 100 to 400 pounds per acre (110 to 450 kilograms per hectare) but are occasionally as high as 600 pounds per acre (680 kilograms per hectare) in low sagebrush habitat types (Bradley et al., 1992). Reestablishment occurs from off-site wind-dispersed seed (Young, 1983). Recovery time of low sagebrush following fire is variable (Young, 1983). After fire, if regeneration conditions are favorable, low sagebrush recovers in 2 to 5 years (Young, 1983). However, on harsh sites where cover is low to begin with and/or erosion occurs after fire, recovery may require more than 10 years (Young, 1983). Slow regeneration may subsequently worsen erosion (Blaisdell et al., 1982). We were unable to find any substantial research on success of seeding low sagebrush after fire.

The effect of fire on bunchgrasses relates to culm density, culm-leaf morphology, and the size of the plant. The initial condition of the bunchgrasses on the site and seasonality and intensity of the fire all factor into the individual species response. Sandberg bluegrass, the dominant grass on this group of ecological sites, may increase following fire likely due to its low stature and productivity (Daubenmire, 1975) and may slow reestablishment of more deeply rooted bunchgrasses.

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), the dominant grass on these communities, response to fire varies with condition and size of the plant, season and severity of fire, and ecological conditions. Mature Idaho fescue plants are commonly severely damaged by fire in all seasons (Wright et al., 1979). Rapid burns leave little damage to root crowns, and production of new tillers corresponds with the onset of fall moisture (Johnson et al., 1994). However, Wright et al. (1979) found the dense, fine leaves of Idaho fescue provided enough fuel to burn for hours after a fire had passed, thereby killing or seriously injuring the plant regardless of the intensity of the fire. Idaho fescue is generally more sensitive to fire than the other prominent grass on these sites such as bluebunch wheatgrass (Conrad & Poulton, 1966). However, Robberecht and Defossé (1995) suggested the latter is more sensitive. They observed culm and biomass reduction of bluebunch wheatgrass following fires of moderate severity, whereas Idaho fescue required high fire severity for a similar reduction in culm and biomass production. Also, given the same fire severity treatment, post-fire culm production initiated earlier and more rapidly in Idaho fescue.

Thurber’s needlegrass (Achnatherum thurberianum), a minor component on these sites, is very susceptible to fire-caused mortality. Burning can decrease the vegetative and reproductive vigor of Thurber’s needlegrass (Uresk et al., 1976). Fire can cause high mortality, in addition to reducing basal area and yield of Thurber’s needlegrass (Britton et al., 1990). The fine leaves and densely tufted growth form make this grass susceptible to subsurface charring of the crowns (Wright & Klemmedson, 1965). Although timing of fire highly influences the response and mortality of Thurber’s needlegrass, smaller bunch sizes are less likely to be damaged by fire (Wright & Klemmedson, 1965). However, Thurber’s needlegrass often survives fire and continues growth when conditions are favorable (Koniak, 1985). Thus, the initial condition of the bunchgrasses on a site along with seasonality and intensity of the fire all factor into the individual species response.

Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda), a minor component of these ecological sites, can increase following fire likely due to its low stature and productivity (Daubenmire 1975) and may retard reestablishment of more deeply rooted bunchgrasses.

The grasses likely to invade the sites in this group are cheatgrass and medusahead. These invasive grasses displace desirable perennial grasses, reduce livestock forage, and accumulate large fuel loads that foster frequent fires (Davies & Svejcar, 2008). Invasion by annual grasses can alter the fire cycle by increasing fire size, fire season length, rate of spread, numbers of individual fires, and likelihood of fires spreading into native or managed ecosystems (D’Antonio & Vitousek, 1992; Brooks et al., 2004). While historical fire return intervals are estimated at 15 to 100 years, areas dominated by cheatgrass are estimated to have a fire return interval of 3 to 5 years (Whisenant, 1990). The mechanisms by which invasive annual grasses alter fire regimes likely interact with climate. For example, cheatgrass cover and biomass vary with climate (Chambers et al., 2007) and are promoted by wet and warm conditions during the fall and spring. Invasive annual species can take advantage of high nitrogen availability following fire because of their higher growth rates and increased seedling establishment relative to native perennial grasses (Monaco et al., 2003).

Livestock/Wildlife Grazing Interpretations:

Domestic sheep and, to a much lesser degree, cattle consume low sagebrush, particularly during the spring, fall, and winter (Sheehy & Winward, 1981). Heavy dormant season grazing by sheep will reduce sagebrush cover and increase grass production (Laycock, 1967). Trampling damage, particularly from cattle or horses, in low sagebrush habitat types is greatest on areas with highly clayey soils during spring snowmelt when surface soils are saturated. On drier areas with more gravelly soils, trampling is less of a problem (Hironaka et al., 1983). Bunchgrasses, in general, best tolerate light grazing after seed formation. Britton et al. (1990) observed the effects of clipping date on basal area of five bunchgrasses in eastern Oregon and found grazing from August to October (after seed set) has the least impact. Heavy grazing during the growing season will reduce perennial bunchgrasses and increase sagebrush (Laycock, 1967). Abusive grazing by cattle or horses allows unpalatable plants like low sagebrush, rabbitbrush, and some forbs such as arrowleaf balsamroot (Balsamorhiza sagittata) to become dominant on the site. Sandberg bluegrass is grazing tolerant due to its short stature. Annual, non-native, weedy species such as cheatgrass, mustards, and medusahead may invade.

Throughout 2 years of site visits, Lahontan sagebrush was observed in a heavily-browsed state on several ecological sites in this group. This recently differentiated subspecies of low sagebrush is moderately to highly palatable to browse species (Winward & McArthur, 1995; McArthur, 2005; Rosentreter, 2005). Dwarf sagebrush species such as Lahontan sagebrush, low sagebrush, and black sagebrush (Artemisia nova) are preferred by mule deer for browse among the sagebrush species.

Bunchgrasses, in general, best tolerate light grazing after seed formation. Britton et al. (1990) observed the effects of clipping date on basal area of five bunchgrasses in eastern Oregon and found grazing from August to October (after seed set) has the least impact. Heavy grazing during the growing season will reduce perennial bunchgrasses and increase sagebrush (Laycock, 1967). Abusive grazing by cattle or horses allows unpalatable plants like low sagebrush, rabbitbrush and some forbs such as arrowleaf balsamroot to become dominant on the site. Sandberg bluegrass is also grazing tolerant due to its short stature. Annual non-native weedy species such as cheatgrass, mustards, and medusahead may invade.

Inappropriate grazing practices can be tied to the success of medusahead. However, eliminating grazing will not eradicate medusahead if it is already present (Wagner et al., 2001). Sheley and Svejcar (2009) reported that even moderate defoliation of bluebunch wheatgrass resulted in increased medusahead density. They suggested that disturbances such as plant defoliation limit soil resource capture, which creates an opportunity for exploitation by medusahead. Avoidance of medusahead by grazing animals allows medusahead populations to expand. This creates seed reserves that can infest adjoining areas and cause changes to the fire regime. Medusahead replaces native vegetation and cheatgrass directly by competition and suppression; it replaces native vegetation indirectly by an increase in fire frequency. Medusahead litter has a slow decomposition rate because of its high silica content, allowing it to accumulate over time and suppress competing vegetation (Bovey et al., 1961; Davies & Johnson, 2008).

Idaho fescue tolerates light to moderate grazing (Ganskopp & Bedell, 1981) and is moderately resistant to trampling (Cole, 1989). However, Idaho fescue decreases under heavy grazing by livestock (Eckert & Spencer, 1986, 1987) and wildlife (Gaffney, 1941). Bunchgrasses, in general, best tolerate light grazing after seed formation. Britton et al. (1979) observed the effects of harvest date on basal area of five bunchgrasses in eastern Oregon, including Idaho fescue, and found grazing from August to October (after seed set) has the least impact on these bunchgrasses. Therefore, abusive grazing during the growing season will reduce perennial bunchgrasses, except for Sandberg bluegrass (Tisdale & Hironaka, 1981).

Thurber’s needlegrass is an important forage source for livestock and wildlife in the arid regions of the West (Ganskopp, 1988). Although the seeds are apparently not injurious, grazing animals avoid them when they begin to mature. Sheep, however, have been observed grazing the leaves closely, leaving stems untouched (Eckert & Spencer, 1987). Heavy grazing during the growing season has been shown to reduce the basal area of Thurber’s needlegrass (Eckert & Spencer, 1987). This suggests that both seasonality and utilization are important factors in management of this plant. A single defoliation, particularly during the boot stage, can reduce herbage production and root mass, thus potentially lowering the competitive ability of this needlegrass (Ganskopp, 1988).

Western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii) and thickspike wheatgrass (Elymus lanceolatus) are two rhizomatous grasses that are often on these sites. Their rhizomatous growth habit makes these grasses tolerant to grazing and more likely to survive fire. These grasses may become more dominant under heavy grazing conditions.

Antelope bitterbrush, although a minor component on these sites, is a critical browse species for mule deer, antelope, and elk and is often utilized heavily by domestic livestock (Wood, 1995). Grazing tolerance depends on site conditions (Garrison, 1953) and the shrub can be severely hedged during the dormant season for grasses and forbs.

Sandberg bluegrass increases under grazing pressure (Tisdale & Hironaka, 1981). It is capable of co-existing with cheatgrass or other weedy species. Excessive sheep grazing favors Sandberg bluegrass; however, where cattle are the dominant grazers, cheatgrass often dominates (Daubenmire, 1970). Thus, depending on the season of use, the type of grazing animal, and site conditions, either Sandberg bluegrass or cheatgrass may become the dominant understory species with inappropriate grazing management.

References:

Beardall, L. E. and V. E. Sylvester. 1976. Spring burning of removal of sagebrush competition in Nevada. In: Tall Timbers fire ecology conference and proceedings. Tall Timbers Research Station. 14:539-547.

Beckstead, J., and Augspurger, C. K. 2004. An experimental test of resistance to cheatgrass invasion: limiting resources at different life stages. Biological Invasions 6:417-432.

Blackburn, W. H., P. T. Tueller, and R. E. Eckert, Jr. 1968a. Vegetation and soils of the Duckwater Watershed. Agricultural Experiment Station. University of Nevada. R40.

Blackburn, W. H., P. T. Tueller, and R. E. Eckert, Jr..1968b. Vegetation and soils of the Crowley Creek Watershed. Agricultural Experiment Station. University of Nevada. R42.

Blackburn, W. H., P. T. Tueller, and R. E. Eckert, Jr., 1969a. Vegetation and soils of the Churchill Canyon Watershed. Agricultural Experiment Station. University of Nevada. R45.

Blackburn, W. H., P. T. Tueller, and R. E. Eckert, Jr., 1969b. Vegetation and soils of the Crane Springs Watershed. Agricultural Experiment Station. University of Nevada. 65 p.

Blaisdell, J. P., R. B. Murray, and E. D. McArthur. 1982. Managing intermountain rangelands-sagebrush-grass ranges. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-134. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Ogden, UT. 41 p.

Bovey, W. R., D. Le Tourneau, and C. L. Erickson. 1961. The chemical composition of medusahead and downy brome. Weeds 9(2):307-311.

Bradford, J. B., and W. K. Lauenroth. 2006. Controls over invasion of Bromus tectorum: The importance of climate, soil, disturbance and seed availability. Journal of Vegetation Science 17(6):693-704.

Bradley, A. F., N. V. Noste, and W. C. Fischer. 1992. Fire ecology of forests and woodlands in Utah. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-287. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station. 128 p.

Britton, C. M., F. A. Sneva, and R. G. Clark. 1979. Effect of harvest date on five bunchgrasses of eastern Oregon. In: 1979 Progress report: Research in Rangeland Management. Special Report 549. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University, Agricultural Experiment Station: Pages 16-19. In cooperation with: U.S. Department of Agriculture, SEA-AR.

Britton, C. M., G. R. McPherson, and F. A. Sneva. 1990. Effects of burning and clipping on five bunchgrasses in eastern Oregon. Great Basin Naturalist 50(2):115-120.

Brooks, M. L., C. M. D'Antonio, D. M. Richardson, J. B. Grace, J. E. Keeley, J. M. Ditomaso, R. J. Hobbs, M. Pellant, and D. Pyke. 2004. Effects of Invasive Alien Plants on Fire Regimes. BioScience 54(7):677-688.

Butler, M., R. Simmons, and F. Brummer. 2011. Restoring Central Oregon Rangeland from Ventenata and Medusahead to a Sustainable Bunchgrass Environment – Warm Springs and Ashwood. Central Oregon Agriculture Research and Extension Center. COARC 2010. Pages 77-82.

Cole, D. N. 1989. Viewpoint: needed research on domestic and recreational livestock in wilderness. Journal of Range Management 42(1):84-86.

Comstock, J. P. and J. R. Ehleringer. 1992. Plant adaptation in the Great Basin and Colorado plateau. Western North American Naturalist 52(3):195-215.

D'Antonio, C. M., and P. M. Vitousek. 1992. Biological invasions by exotic grasses, the grass/fire cycle, and global change. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 23:63-87.

Daubenmire, R. 1970. Steppe vegetation of Washington. Technical bulletin 62. Washington Agriculture Experiment Station. 131 p.

Daubenmire, R. 1975. Plant succession on abandoned fields, and fire influences in a steppe area in southeastern Washington. Northwest Science 49(1):36-48.

Davies, K. W., and D. D. Johnson. 2008. Managing medusahead in the intermountain west is at a critical threshold. Rangelands 30(4):13-15 .

Davies, K. W., and T. J. Svejcar. 2008. Comparison of medusahead-invaded and noninvaded Wyoming big sagebrush steppe in southeastern Oregon. Rangeland Ecology and Management 61(6):623-629.

Davies, K. W., A. M. Nafus, and M. D. Madsen. 2013. Medusahead invasion along unimproved roads, animal trails, and random transects. Western North American Naturalist 73(1):54-59.

Davies, K. W., C. S. Boyd, D. D. Johnson, A. M. Nafus, and M. D. Madsen. 2015. Success of seeding native compared with introduced perennial vegetation for revegetating medusahead-invaded sagebrush rangeland. Rangeland Ecology & Management 68(3):224-230.

Dobrowolski, J. P., M. M. Caldwell, and J. H. Richards. 1990. Basin hydrology and plant root systems. Pages 243-292 in: C. B. Osmand, L. F. Pitelka, G. M. Hildy (eds). Plant biology of the Basin and range. Ecological Studies. Springer-Verlag, New York.

Fosberg, M. A., and M. Hironaka. 1964. Soil properties affecting the distribution of big and low sagebrush communities in southern Idaho. American Society of Agronomy Special Publication No. 5. Pages 230-236.

Furbush, P. 1953. Control of Medusa-Head on California Ranges. Journal of Forestry 51(2):118-121.

Furniss, M. M. and W. F. Barr. 1975. Insects affecting important native shrubs of the northwestern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-19. Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Ogden, UT. 68 p.

Ganskopp, D. C., and T. E. Bedell. 1981. An assessment of vigor and production of range grasses following drought. Journal of Range Management 34(2):137-141.

Gruell, G. E. 1999. Historical and modern roles of fire in pinyon-juniper. In: S. B. Monsen and R. Stevens, (comps.). Proceedings: Ecology and management of pinyon-juniper communities within the Interior West. 1997, September 15-18. Provo, UT. Proceedings RMRS-P-9. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Provo, UT. Pages 24-28.

Harris, G. A. 1967. Some Competitive Relationships between Agropyron spicatum and Bromus tectorum. Ecological Monographs 37(2):89-111.

Hironaka, M., M. A. Fosberg, and A. H. Winward. 1983. Sagebrush-grass habitat types of southern Idaho. Bulletin Number 35. University of Idaho, Forest, Wildlife and Range Experiment Station, Moscow, ID.

Hironaka, M. 1994. Medusahead: Natural Successor to the Cheatgrass Type in the Northern Great Basin. In: Proceedings of Ecology and Management of Annual Rangelands. USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-GTR-313. Pages 89-91.

James, J., K. Davies, R. Sheley, and Z. Aanderud. 2008. Linking nitrogen partitioning and species abundance to invasion resistance in the Great Basin. Oecologia 156(3):637-648.

Jameson, D. A. 1970. Juniper root competition reduces basal area of blue grama. Journal of Range Management 23(3):217-218.

Johnson, B. G.; Johnson, D. W.; Chambers, J. C.; Blank, B. R. 2011. Fire effects on the mobilization and uptake of nitrogen by cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum L.). Plant and Soil 341(1-2):437-445.

Johnson, C. G., R. R. Clausnitzer, P. J. Mehringer, and C. Oilver. 1994. Biotic and abiotic processes of eastside ecosystems: The effects of management on plant and community ecology, and on stand and landscape vegetation dynamics. PNW-GTR-322. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Portland, OR. 66 p.

Klemmedson, J. O., and J. G. Smith. 1964. Cheatgrass (Bromus Tectorum L.). The Botanical Review 30(2):226-262.

Knick, S. T., Holmes, A. L. and Miller, R. F. 2005. The role of fire in structuring sagebrush habitats and bird communities. Studies in Avian Biology 30:63-75.

Koniak, S. 1985. Succession in pinyon-juniper woodlands following wildfire in the Great Basin. The Great Basin Naturalist 45(3):556-566.

Mack, R. N., and D. Pyke. 1983. The Demography of Bromus Tectorum: Variation in Time and Space. Journal of Ecology 71(1):69-93.

MacMahon, J. A. 1980. Ecosystems over time: succession and other types of change. In: Waring, R., ed. Proceedings—Forests: fresh perspectives from ecosystem analyses. Biological Colloquium. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University. Pages 27-58.

Mangla, S., R. Sheley, and J. J. James. 2011. Field growth comparisons of invasive alien annual and native perennial grasses in monocultures. Journal of Arid Environments 75(2):206-210.

McArthur, E. D. 2005. View Points: Sagebrush, Common and Uncommon, Palatable and Unpalatable. Rangelands 27(4):47-51.

Miller, H. C., Clausnitzer, D., and Borman, M. M. 1999. Medusahead. In: R. L. Sheley and J. K. Petroff (eds.). Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press. Pages 272-281.

Miller, R. F., and J. A. Rose. 1995. Historic expansion of Juniperus occidentalis (western juniper) in southeastern Oregon. Western North American Naturalist 55(1):37-45.

Miller, R. F., R. J. Tausch, E. D. McArthur, D. D. Johnson, and S. C. Sanderson. 2008. Age structure and expansion of pinon-juniper woodlands: a regional perspective in the Intermountain West. Research Paper RMRS-RP-69. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO. 15 p.

Miller, R. F., Chambers, J. C., Pyke, D. A., Pierson, F. B. and Williams, C. J., 2013. A review of fire effects on vegetation and soils in the Great Basin Region: response and ecological site characteristics. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-308. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 126 p.

Monaco, T. A., Charles T. Mackown, Douglas A. Johnson, Thomas A. Jones, Jeanette M. Norton, Jay B. Norton, and Margaret G. Redinbaugh. 2003. Nitrogen effects on seed germination and seedling growth. Journal of Range Management 56(6):646-653.

Pellant, M., and C. Hall. 1994. Distribution of two exotic grasses in intermountain rangelands: status in 1992. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech Report INT-GTR- 313S. Pages 109-112.

Ralphs, M. H., and F. E. Busby. 1979. Prescribed burning: vegetative change, forage production, cost, and returns on six demonstration burns in Utah. Journal of Range Management 32(4):267–270.

Rice, P. M. 2005. Medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusae (L.) Nevski). In: C. L. Duncan and J. K. Clark (eds.). Invasive plants of range and wildlands and their environmental, economic, and societal impacts. Weed Science Society of America, Lawrence, KS.

Rosentreter, R. 2005. Sagebrush Identification, Ecology, and Palatability Realtive to Sage Grouse. In: Shaw, Nancy L.; Pellant, Mike; Monsen, Stephen B., (comps.). Sage-grouse habitat restoration symposium proceedings; 2001 June 4-7, Boise, ID. Proc. RMRS-P-38. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Vol. 38: 3-16.

Sheley, R. L., and Svejcar T.J. 2009. Response of bluebunch wheatgrass and medusahead to defoliation. Rangeland Ecology & Management 62(3):278-283.

Sheley, R. L., E. A. Vasquez, A. Chamberlain, and B. S. Smith. 2012. Landscape-scale rehabilitation of medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusae)-dominated sagebrush steppe. Invasive Plant Science and Management 5(4):436-442.

Smith, M. A., and F. Busby. 1981. Prescribed burning, effective control of sagebrush in Wyoming. Agricultural Experiment Station. RJ-165. University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming, USA. 12 p.

Tausch, R. J., N. E. West, and A. A. Nahi. 1981. Tree age and dominance patterns in great basin pinyon- juniper woodlands. Journal of Range Management 34(4):259-264.

Tausch, R. J. 1999. Historic pinyon and juniper woodland development. In: S. B. Monsen and R. Stevens, (comps.). Proceedings: Ecology and management of pinyon-juniper communities within the Interior West. 1997, September 15-18. Provo, UT. Proceedings RMRS-P-9. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Provo, UT. Pages 12-19.

Tisdale, E. W. and M. Hironaka. 1981. The sagebrush-grass region: A review of the ecological literature. Bulletin 33. University of Idaho, Forest, Wildlife and Range Experiment Station. Moscow, ID. 31 p.

Tueller, P. T., and J. E. Clark. 1975. Autecology of pinyon-juniper species of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau. In: G. F. Gifford and F. E. Busby, (eds.). The pinyon-juniper ecosystem: a symposium. 1975. Utah State University, Logan, UT. Pages 27-40.

Vollmer, J. L., and J. G. Vollmer. 2008. Controlling cheatgrass in winter range to restore habitat and endemic fire United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. RMRS-P-52. Pages 57-60.

Wagner, J. A., R. E. Delmas, J. A. Young. 2001. 30 years of medusahead: return to fly blown-flat. Rangelands 23(3):6-9.

Weisberg, P. J., and D. W. Ko. 2012. Old tree morphology in singleleaf pinyon pine (Pinus monophylla). Forest Ecology and Management 263:67-73.

West, N. E., K. H. Rea, and R. J. Tausch. 1975. Basic synecological relationships in pinyon-juniper woodland. In: The pinyon-juniper ecosystems: a symposium. Utah Agricultural Experiment Station. Pages 41-54.

West, N. E., R. J. Tausch, and P. T. Tueller. 1998. A management-oriented classification of Pinyon-Juniper woodlands of the Great Basin. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-12, USDA, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Ogden, UT. 42 p.

Whisenant, S., 1999. Repairing Damaged Wildlands: a process-orientated, landscape-scale approach (Vol. 1). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 312 p.

Winward, A. H. 1980. Taxonomy and ecology of sagebrush in Oregon. Station Bulletin 642. Oregon State University Agricultural Experiment Station. Corvallis, OR. 15 p.

Winward, A. H., and E. D. McArthur. 1995. Lahontan sagebrush (Artemisia arbuscula ssp. longicaulis): a new taxon. Great Basin Naturalist 55(2):151-157.

Wright, H. A., L. F. Neuenschwander, and C. M. Britton. 1979. The role and use of fire in sagebrush-grass and pinyon-juniper plant communities: A state-of-the-art review. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-58. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 48 p.

Young, R. P. 1983. Fire as a vegetation management tool in rangelands of the intermountain region. In: Monsen, S. B. and N. Shaw (eds). Managing Intermountain rangelands—improvement of range and wildlife habitats: Proceedings. 1981, September 15-17; Twin Falls, ID; 1982, June 22-24; Elko, NV. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-157. Ogden, UT. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. Pages 18-31.

Zamora, B., and Tueller, P. T. 1973. Artemisia arbuscula, A. longiloba, and A. nova habitat types in northern Nevada. Great Basin Naturalist 33(4):225-242.

Major Land Resource Area

MLRA 023X

Malheur High Plateau

Stage

Provisional

Contributors

T Stringham (UNR under contract with BLM)

DMP

Click on box and path labels to scroll to the respective text.